Biography

Interests

Mauro Castelló González1* & Imti Choonara2

1Department of Paediatric Surgery, Camagüey Paediatric Hospital, Cuba

2Academic Unit of Child Health, University of Nottingham, Derbyshire Children’s Hospital, Derby, UK

*Correspondence to: Dr. Mauro Castelló González, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Camagüey Paediatric Hospital, Cuba.

Copyright © 2018 Dr. Mauro Castelló González, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Child health varies significantly between countries and different regions. Child mortality is lowest in Europe and highest in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia [1]. There are however wide variations between different countries in the same region and also significant variations within countries. Socio-economic inequalities are a major determinant of health outcomes. The provision of universal health care is a major contributory factor to reducing inequalities and child mortality.

Globally, the under 5 mortality rate (U5MR) has fallen from 93 deaths per 1000 live births in 1990 to 41 in 2016 [1]. The U5MR is considered by UNICEF to be a key marker of how states look after their children. The figures above mean 15,000 children under the age of 5 years die every day. In 1990, the figure was 35,000 deaths daily.

Under five child mortality is highest in the neonatal period – with prematurity and sepsis being major causes [1]. The absence of a health professional at birth significantly increases the risk of both morbidity and mortality in the neonatal period. Some countries have a health professional present at less than 50% births [2]. Infections are a major contributor to child mortality after the neonatal period. Pneumonia, diarrhea and malaria account for almost one third of deaths worldwide in children under the age of 5 years [1]. These three conditions are all treatable and in many cases preventable.

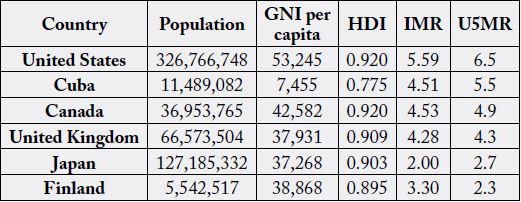

Universal health care including a comprehensive immunization program alongside universal education can significantly reduce child mortality. Two other key features include adequate nutrition and access to clean water and sanitation [3]. High income countries have introduced many of these factors, with varying success. The USA does not have universal health care and this is associated with higher levels of child mortality (Table 1) than other high income countries [1,4]. The USA actually has higher child mortality rates than Cuba, a middle income country. How has Cuba achieved such impressive results?

GNI: Gross National Income (PPP $)

HDI: Human Development Index

IMR: Infant Mortality Rate

U5MR: Under 5 Mortality Rate

Cuba

Cuba’s achievements in child health are due to a combination of factors. The first of these is the political will

of the Cuban government to recognize health as a priority. Cuba has an integrated health care system with

all sections cooperating fully. Universal health care and universal education are the basis for good health.

Literacy is at 99.7% and this enables public health campaigns to reach the entire population. Free universal

education has resulted in Cuba having one of the highest doctor to population ratios.

A comprehensive immunization program includes 10 vaccines protecting against 13 infectious diseases. Cuba was the first Latin American country to eradicate poliomyelitis and as of 2016 had eliminated 5 other infectious diseases. There is a strong antenatal program that has resulted in a low incidence of low birth weight babies [5]. Primary health care is well established with an emphasis on the prevention of disease. Maternity leave has recently been extended to 12 months and breast feeding is encouraged. Screening for fetal congenital malformations is offered as part of the antenatal care.

A positive attitude towards disability is encouraged. The presence of an educated population reduces misconceptions and stigma associated with disability and epilepsy. There is a focus on public health alongside investment in an excellent primary health care structure. Almost half of all Cuban doctors work in primary health care. Polyclinics provide a link between primary health care and hospitals.

As well as providing excellent health care to Cubans, Cuba has played a major role in providing health care to other countries. Over 50,000 Cuban health professionals work in over 60 countries worldwide [5]. Cuba has provided emergency assistance following natural disasters ranging from earthquakes to floods. Its contribution to the fight against Ebola has been recognized by the WHO. Cuba has also tried to improve primary and secondary health care in numerous countries on a collaborative basis. High and middle income countries such as Qatar and Brazil pay for the Cuban health professionals, whereas low income countries such as Haiti do not pay.

Cuba is also training doctors in many other countries. The Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM) in Havana also teaches students from around the world. Over 23,000 students from 83 countries have already graduated [6]. Cuba is unique in that; it is trying to reverse the brain drain whereby health professionals from low income countries go to high income countries.

Cuba has shown that despite limited resources, a country can achieve excellent child health, if the government and citizens are committed to making health and children a priority. Cuba is an example of what is possible.

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!