CPQ Orthopaedics (2021) 5:5Literature Review

The Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sports Participants in

Zimbabwe

Bibiana Ncube & Eberhard Tapera, M.*

National University of Science & Technology, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

*Correspondence to: Dr. Eberhard Tapera, M., National University of Science & Technology, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

Copyright © 2021 Dr. Eberhard Tapera, M., et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received: 01 September 2021

Published: 14 September 2021

Keywords: COVID-19 Pandemic; Lock-Down; Sports; Disciplines

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic seems to have affected sport negatively in Zimbabwe and the whole

world. This descriptive study sought to investigate the effect of the lock-down, a response to the

COVID-19 pandemic, on sports participants in Zimbabwe. Data for the study were collected from

ten respondents (5 coaches and 5 players) randomly drawn from the disciplines athletics, basketball,

soccer, table tennis and volleyball, who each responded to a self-administered online questionnaire.

The responses were condensed into frequency tables and presented graphically. The study found

that most players have reduced their training load, and feel fatigued and depressed, as a result of the

lock-down. The study further found that a substantial number of sports participants has changed

their diet for the worse and have had their sleeping patterns disturbed as a result of the lockdown.

It is concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic had negative effects on the mental health,

sleep patterns, and training levels of sportspersons in Zimbabwe. Sports teams in Zimbabwe are

therefore advised to implement programs that will improve the training status, eating and sleeping

habits of sports persons in Zimbabwe, and address feelings of depression among them. Further

similar studies could include sports participants in managerial positions.

Introduction

Sports is regarded as an important part of modern life, which contributes to community identity, health, and

economic and social development, among other things. The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in reduced

and restricted sports participation and gatherings, to varying levels in the whole world. According to Rattern

(2020) [1] the sporting sector has been affected by the COVID-19 crisis in a way that has never been

seen before. All physically activity and team sports were suddenly restricted in many countries, often being

relegated to home-based individual physical training [2,3]. This has seen almost all sport codes in Zimbabwe

also being restricted and shut down from the public. One would expect that players and coaches, among

many others, to have been hardest hit by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Few studies have been conducted to ascertain the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on sportspersons in

Zimbabwe. The researchers therefore sought to study the ways in which players and the coaches of different

sports have been affected by this pandemic. Results from the study will hopefully assist in coming up with

strategies to continue with sports during, or after the pandemic.

Literature Review

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused, and continues to cause, one of the most significant disruption to

sporting calendars world-wide [4]. and prevent over-whelming the healthcare system.

All local and international competitions and events were cancelled, postponed, or restricted as a result of the

COVID-19 pandemic, with numerous mostly negative consequences. As a result of the fact that the global

sporting calendar is rearranged to accommodate the postponement of the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics,

for example, other events may be squeezed into the months that follow, posing risks of overtraining and

over-competition for athletes. Postponement and cancellation of sports has potential costs in terms of

compromised athlete development and loss of competition experience and declining athlete motivation.

Other possible negative effects include mental health, physical health and nutritional health [5,6].

Methodology

The research followed a cross-sectional survey research design. The population for the study comprised of

five of the forty-eight sports disciplines which are recognized by the Sports and Recreation Commission Act

(2001) [7]. A sample of five sport disciplines was purposively selected to yield participants from athletics,

basketball, football, table tennis and volleyball. Two participants per sport discipline (one coach and one

player) were selected through the use of a simple random sampling technique. The researchers used online

questionnaires to which the respondents answered via WhatsApp. We considered this instrument very

relevant in view of the restrictions that were obtaining. A web link with the questionnaire was sent to all the

participants via an email together with the instructions, covering letter and consent forms. The results were

condensed into frequency tables and presented graphically.

Some Results

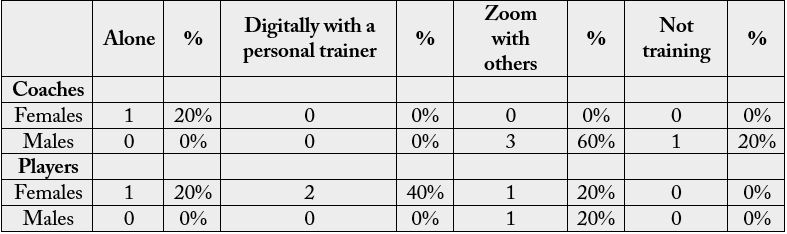

Maintaining Activity During Lockdown

From these data only a fifth of athletes trained alone, while less than half trained digitally.

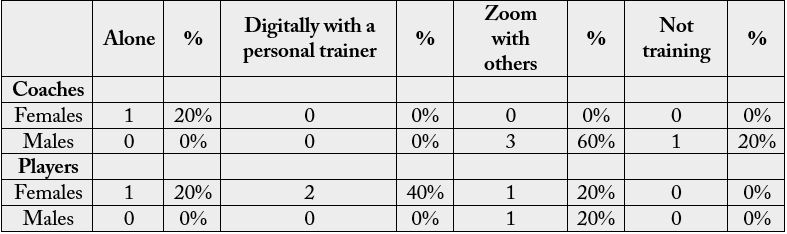

Motivation to Exercise

From this graphical depiction of motivation to exercise, both player- and coach-motivation to exercise had

reduced during the lockdown [8-64].

Summary Conclusions and Recommendations

This study investigated the effect of COVID-19 on the different sport codes in Zimbabwe. Data for the

research was collected from five national sports associations in Zimbabwe. Five coaches and five players from athletics, basketball, football, table tennis and volleyball, were selected for the study. A self-administered

questionnaire was used to collect data. The study found that most players have reduced their training, feel

fatigued and depressed as a result of the lock-down. The study further found that a substantial number of

sports participants has changed their diet for the worse and have had their sleeping patterns disturbed as a

result of the lock-down. It is concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic had negative effects on the mental

health, sleep, and training levels of sportspersons in Zimbabwe. Sports teams in Zimbabwe are advised to

implement programs that will improve the training status, eating and sleeping habits of sports persons in

Zimbabwe, and address feelings of depression among them. Further similar studies could include sports

participants in managerial positions.

Bibliography

- Ratten, V. (2020). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and Sport Entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res., 26(6), 1379-1388.

- Memish, Z. A., Steffen, R., White, P., Dar, O., Azhar, E. I., Sharma, A. & Zumla, A. (2019). Mass Gatherings Medicine: Public Health Issues Arising from Mass Gathering Religious and Sporting Events. Lancet, 393(10185), 2073-2084.

- Stanton, R., Quyen, T., Khalesi, S., Williams, S. L., Alley, S. J., Thwaite, T. L., Fenning, A. S. & Vandelanotte, C. (2020). Depression, Anxiety and Stress during COVID-19: Associations with Changes in Physical Activity, Sleep, Tobacco and Alcohol Use in Australian Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health., 17(11), 4065.

- Ying-Ying Wong Ashley, Ka-Kin Ling Samuel, Louie Lobo, Ying-Kan Law George, Chi-Hung So Raymond, Chi-Wo Lee Daniel, et al. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sports and exercise. Asia-Pacific Journal of Sports Medicine, Arthroscopy, Rehabilitation and Technology, 22, 39-44.

- Ng, K. (2020). Adapted physical activity through COVID-19. European Journal of Adapted Physical Activity, 13(1), 1.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services (2018). 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report.

- Simion, G. H., Mihăilă, I. & Stănculescu, G. (2011). Sports systemic concept training. Ovidius University Press, Constanta. Sports and Recreation Commission Act. (2001). Chapter 25:15 Act 15/1991, 22/2001 (s. 4).

- Afsanepurak, S. A., Hossini, R. N. A., Seyfari, M. K. & Fathi, H. (2012). Analysis of motivation for participation in sport for all. International Research Journal of Applied and Basic Sciences, 3(4), 790-795.

- Almeida, P. L. & Lameiras, J. (2013). You’ll never walk alone: cooperation as an explanatory paradigm of the dynamics of sports team. Revistade Psicologíadel Deporte, 22(2), 34-48.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) (2007). Motivators and Constraints to Participation in Sports and Physical Recreation. National Centre for Culture and Recreation Statistics, (Pp. 1-32).

- Babbie, E. & Mouton, J. (2001). The ethics and politics of social research. The practice of social research.

- Bauman, A., Bellew, B., Vita, P., Brown, W. & Owen, N. (2002). Getting Australia active: towards better practice for the promotion of physical activity. National Public Health Partnership, Melbourne.

- Bird, A. M. (1977). Team structure and success as related to cohesiveness and leadership. Journal of Social Psychology, 103(2), 217-223.

- Bollen, K. A. & Hoyle, R. H. (1990). Perceived cohesion: A conceptual and empirical examination. Social Forces, 69(2), 479-504.

- Bompa, T. O. (2001). The Theory and Methodology of Training. Second edition, CNFPA Press, Bucharest.

- Bowman, K. G. (2014). Research recognition, the first step to research literacy. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 45(9), 409-415.

- Bray, C. D. & Whaley, D. E. (2001). Team cohesion, effort and objective individual performance of high school basketball players. Sport Psychologists, 15(3), 260-275.

- Burrows, K., Maiyegun, O., Rhind, D. & Rozga, D. (2020). An Overview of the Sport Related Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children. Centre for Sport and Human Rights.

- Carron, A. V. (1982). Cohesiveness in sport groups: Interpretations and considerations. Journal of Sport Psychology, 4, 123-138.

- Carron, A. V., Brawley, L. R. & Widmeyer, N. W. (1998). The measurement of cohesion in sport groups. In J. L. Duda (Ed.), Advances in sport and exercise psychology measurement (pp. 213-226). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Carron, A. V., Bray, S. R. & Eys, M. A. (2002). Team cohesion and team success in sport. Journal of Sports Sciences, 20(2), 119-126.

- Carron, A. V. & Dennis, P. (2001). The sport team as an effective group. In J.M. Williams (Ed.), Applied sport psychology: Personal growth to peak performance (4th ed.) (pp. 120-134). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield.

- Carron, A. V. & Spink, K. S. (1995). The group size cohesion relationship in minimal groups. Small Group Research, 26(1), 86-105.

- Chau, J. (2007). Physical activity and building stronger communities. NSW Centre for Physical Activity and Health, Sydney.

- Coakley, J. (2001). Sport in Society: Issues and controversies. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Coggins A., Swanston, D., & Crombie, H. (1999). Physical activity and inequalities: A Briefing Paper, Health Education Authority, London.

- Department of Health South Africa (DOHSA) (2015). Strategy for the prevention and control of obesity in South Africa 2015-2020.

- Desrochers, D. M. (2013). Academic Spending Versus Athletic Spending: Who Wins? Delta cost projects at American Institute for Research.

- Dawson, C. (2002). Practical Research Methods: A user-friendly guide to mastering research techniques and projects. Oxford OX4 1RE. United Kingdom.

- Eben, W. & Brudzynski, L. (2008). Motivations and barriers to exercise among college students. Journal of Exercise Physiology, 11, 1-11.

- Frels, R. K. & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2013). Administering quantitative instruments with qualitative interviews: A mixed research approach. Journal of Counselling and Development, 91(2), 184-194.

- Henchy, A. (2011). The influence of campus recreation beyond the gym. Recreational Sports Journal, 35(2), 174-181.

- Hesse-Biber, S. (2016). Qualitative or mixed methods research inquiry approaches: Some loose guidelines for publishing in sex roles. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 74(1-2), 6-9.

- Hoe, W. E. (2007). Motives and constraints to physical activities participation among undergraduates. Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia: Universiti Teknologi MARA.

- Jackson, E. L. (2000). Will research on leisure constraints still be relevant in the twenty-first century? Journal of Leisure Research, 32(1), 62-68.

- Kahn, E., Ramsay, L., Brownson, R., Heath, G., Howze, E., Powell, K., Stone E., Rajab, M., Phaedre Corso M and the Task Force on Community Preventive Services (2002). The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity. A systematic review, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 22(4 Suppl 1), 73-107.

- McCurry, J. & Ingle, S. (2020). Tokyo Olympics postponed to 2021 due to coronavirus pandemic. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077.

- McGuirk, E. & Prentice, G. (2012). Physical activity, its relationship with psychological wellbeing and self-perception, and in keeping us all psychologically healthier. Unpublished BA thesis. DBS School of Arts.

- Mullen, B. & Copper, C. (1994). The relation between group cohesiveness and performance: An integration. Psychological Bulletin, 115(2), 210-227.

- Nieman, D. C. & Pedersen, B. K. (1999). Exercise and Immune Function: Recent Developments. Sports Medicine, 27(2), 73-80.

- Nixon, H. L. (1976). Team orientations, interpersonal relations, and team success. Research Quarterly, 47(3), 429-435.

- Olmedilla, A., Ortega, E., Almeida, P. L., Lameiras, J., Villalonga, T., Sousa, C. & García-Mas, A. (2011). Cohesion and cooperation in sports teams. Anales de Psicología, 27(1), 232-238.

- Papanikolaou, Z., Patsiaouras, A. & Keramidas, P. (2003). Family systems approach in building soccer team. Inquiries in Sport & Physical education, 1, 116-123.

- Peters, N., Scholtz, E, M. & Weilbach, J. T. (2014). Determining the demand for recreational sport at a university. Unpublished MA mini-thesis. North-West University. Potchefstroom, South Africa Department of Psychology. Dublin, Ireland.

- Peterson, A. J. & Martens, R. (1972). Success and residential affiliation as determinants of team cohesiveness. Research Quarterly, 43(1), 62-76.

- Peterson, A. R., Nash, E. & Anderson, B. J. (2019). Infectious Disease in Contact Sports. Sports Health, 11(1), 47-58.

- Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee (2018). Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services.

- Reardon, C. (2017). Psychiatric Comorbidities in Sports. Neurologic Clinics, 35(3), 537-546.

- Sustrans, L. (2010). Active travel and mental well-being. The benefits of physical activity for mental health.

- Townsend, M., Moore, J. & Mahoney. M. (2002). Playing their part: the role of physical activity and sport in sustaining the health and wellbeing of small rural communities. The International Electronic Journal of Rural and Remote Health, 2, 109.

- Veit, H. (1973). Interpersonal relations and the effectiveness of ball game tennis. In Proceedings of the Third International Congress of Sport Psychology. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Education Fisica Deportes.

- WHO (2020). Virtual Press Conference on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020.

- Walsh, N. P. & Oliver, S. J. (2016). Exercise, immune function and respiratory infection: An update on the influence of training and environmental stress. Immunol Cell Biol., 94(2), 132-139.

- Webber, D. J. & Mearman, A. (2005). Student participation in sporting activities. Applied Economics, 41(9), 1183-1190.

- Weinberg, R. S. & Gould, D. (2011). Foundations of sport and exercise psychology (5th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Widmeyer, W. N., Carron, A.V. & Brawley, L. R. (1993). Group cohesion in sport and exercise. In R.N. Singer, M. Murphey& L.K. Tennant (Eds.), Handbook of research on sport psychology (pp. 672-692). New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Williams, J. M. & Widmeyer, W. N. (1991). The cohesion-performance outcome relationship in a coaching sport. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 13, 364-371.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2010). Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2014). Global status report on non-communicable diseases 2014.

- Classic 263 (2020). Zim Sports: competitive action to resume in 2021.

- New Zimbabwe (2020). SRC maintains ban on sporting activities.

- New Zimbabwe (2020). SRC provides conditions for resumption of activities.

- New Zimbabwe (2020). Sports Ministry proposes conditions for football return.

- New Zimbabwe (2020). Govt Bans All Sporting Activities After New Lockdown Measures.