Biography

Interests

Ray Marks

Departments of Health and Behavior Studies, Columbia University, Teachers College, New York, NY, USA

*Correspondence to: Dr. Ray Marks, Departments of Health and Behavior Studies, Columbia University, Teachers College, New York, NY, USA.

Copyright © 2020 Dr. Ray Marks. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Hip fractures, which remain an important costly health concern in aging populations that commonly lead to disabling hip osteoarthritis, and or premature death continue to occur despite a general fracture reduction amidst the 2020 coronavirus lock-down period. Although generally amenable to emergency room admittance followed by treatment, a question arises as to whether there is any tangible impact on survival, mobility and independence recovery, and possible life quality in the midst of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, and if so, what lessons can be learned to date, if indeed, a second wave of this infectious disease is predicted. To address these questions, this mini review elected to examine all available and pertinent literature sources published in the peer reviewed English language between January 1 2020 and Aug 10 2020 concerning hip fractures and COVID-19 regardless of report type. The aim was to identify if specific interventions to offset the risk of incurring this injury and its attendant disability and possible highly adverse additional orthopaedic outcomes are warranted at this time of widespread lock downs and service closures or delays. We conclude that based on current evidence multi-pronged efforts to maximize the musculoskeletal health of older adults living in the community, along with health and safety education is strongly indicated to reduce the incidence and severity of hip fracture injuries and their increasingly adverse outcomes, especially among those with osteoporotic disease and COVID-19 infections. Rehabilitation outcomes may be similarly improved by such an approach, along with prolonged tailored and targeted follow-up strategies to ensure lock-downs do not excessively compromise the health and musculoskeletal status of the recovering community dwelling older hip fracture patient.

Introduction

In recent years, hip fractures have been viewed as one of the most serious health care problems facing

policy makers, health care organizations, and older adults living in the community. Indeed, although some

evidence of a decline in hip fracture prevalence has recently been reported [e.g., 1, 2], the injury remains an

ever present and potentially unwarranted cause of severe disability, excess morbidity, reduced life quality and

premature mortality among older adults [3]. Moreover, according to some, it is just as likely that the annual

incidence of hip fractures could increase, rather than decrease, over the next several decades [4]. In addition,

data do not usually account for the fact that a ‘first’ hip fracture incident may increase the risk of a ‘second’

similar ipsilateral or contralateral injury, plus other non-hip fragility fractures that require hospitalization as

well as exposure to hip fracture-related complications [3] as well as COVID-19 infections, more recently.

Moreover, in a 10 year prospective study the reversal of the hip fracture secular trend was found related to

a decrease in the incidence of hip fractures among institution-dwelling elderly women, which fell by 1.9%

per year (p = 0.044), rather than among community-dwelling woman where it remained stable (+0.0%, p =

0.978). As well, rates of hip fracture over time did not appear to fall in Germany [5], rates appeared to be

increasing among older women in Taiwan [6], and in men, no significant change in hip fracture incidence

occurred among institution- or community-dwelling elderly, suggesting residential status is a factor in

explaining hip fracture incidence rates [7]. Rates may also depend on the region studied [8].

Thus, even though rates of hip fracture may be declining in specific localities, since hip fracture rates as a whole still tend to rise exponentially with age [9], as populations age and longevity increases [10], the annual numbers of new hip fracture cases along with their related costs are also certain to rise unless action is taken among communities to prevent these or at least reduce the chances of hip fracture risk attributable to modifiable factors. This situation is not straightforward however, and is clearly compounded by increasing numbers of older adults at risk for hip fractures due to the presence of one or more chronic health problems, such as diabetes. Indeed, if as is predicted, more people reach age 85 where they are 10-15 times more likely to sustain a hip fracture [11], and that a vast majority of hip fractures injuries in the 21st century will occur in developing countries [12], more, rather than fewer, hip fracture occurrences overall can be anticipated globally.

Given that the prevailing overall burden, as well as the projected public health care burden of this debilitating injury [10] that is not limited solely to the costs of functional disability and increased death rates, but commonly also to a loss of the independent functional ability of the injured adult, plus related anaesthesia, nursing care, long-term care and surgery costs, continued vigilance in preventive strategies against hip fracture as outlined by Wilson and Wallace [10] appear to be highly desirable, if not essential and valid, human and social investments.

Indeed, this idea concerning more input into the implementation of sound evidence based primary prevention against hip fractures in the older population seems even more imperative than ever in 2020 in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, which affects the elderly significantly and disproportionately, and which commonly involves varying degrees of social isolation, as well as reactions such as depression and fears that may heighten the overall risk for both fragility as well as falls, while at the same time potentially exacerbating this situation are unanticipated and unprecedented losses of preventive programs to offset hip fracture risk, along with possible weekly pharmacy visits for biphosphonate checks and others. At the same time, other ensuing determinants for hip fractures such as osteoporosis and diabetes may be heightened due to unanticipated nutritional as well as pharmacologic challenges, along with a higher risk of stress related cardiovascular disease problems, rendering this group highly prone to fragility fractures, as well as falls, and COVID-19 infections.

There is also a tremendous burden now placed on available health care resources in the event of a fracture injury, as outlined by Hadfield and Gray [13] and where patients in Britain needing treatment are increasingly treated as day case admissions where non-operative management approaches are initiated wherever possible. As well, many hospitals and wards have merged to facilitate the creation of COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 areas with separate teams allocated to each to reduce cross infection between staff members and patients and early patient discharge has allowed an increase in available bed space and reallocation of clinical staff to enable capacity and ensure patient safety standards, thus less intensive hip fracture care is likely, with more emphasis on conservative treatment-which is less effective than surgery. Moreover, although as a society, social distancing and travel restrictions appear to have reduced emergency department admissions in Britain to an all time low, hip fractures among the elderly are shown to still be generally admitted at an unchanged rate.

This latter finding is very important, because in this report by Hadfield and Gray [13], the authors further mention that early observations and a departmental audit of hip fracture patients admitted during March and April of 2020 and who were surgically stabilized, showed a trend to higher 30-day mortality rates in those patients who subsequently tested COVID positive after surgery compared to those who did not. Prevention of either hip fractures or COVID infections or both however, are not mentioned explicitly, although more efficient targeted multi dimensional post surgical approaches are recommended.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, Jurisson et al. [14] reported finding a high immediate excess risk of death in older age groups (≥80 years) and gradually accumulating excess risk in younger age groups (50-79 years). The excess risk was more pronounced among men than women, and it was concluded that at the end of a 10-year follow-up, 1 in 4 deaths in the hip were attributable to the presence of a hip fracture, thus the argument was made for the fact that the presence of a hip fracture in the older adult is a highly powerful independent risk factor for excess mortality.

Aim

This present mini review aimed to examine if there is currently a steady incidence of hip fracture injuries

that are possibly requiring intense care in the hospital, plus excess treatment follow ups due to COVID-19

related factors. Since COVID-19 is prevalent worldwide, and most societies are aging, and may be severely challenged at this pandemic time, our aim was to examine and describe the early mortality rate and other

data pertaining to hip fracture samples that have been examined to date during the coronavirus pandemic.

A second aim was to derive any lessons that could be learned currently, so as to be more prepared if a ‘second

wave’ of the virus prevails.

Rationale

The frail elderly, as well as hip fracture survivors and those with one or more common comorbid conditions

are potentially an important older group to target during the present pandemic because those vulnerable to

COVID-19, such as this group, tend to have more complicated hip fracture recovery rates than those who

are healthy and non frail [15]. They may also recover more slowly from COVID-19 than healthy older adults,

thus increasing the overall costs of this health condition, which are already immense. In addition, poorly or

sub-optimally treated hip fractures may not only exacerbate the ensuing level of functional disability that

arises, but may foster an environment that heightens the risk of a hip fracture recurrence or a fracture of the

contra-lateral hip, that is even more debilitating. Hospitalizations also expose elderly patients to COVID-19

even if timely surgery and rehabilitation strategies for restoring functional recovery post-hip fracture surgery

are available, thus more preventive efforts to secure the health and safety of the older community dwelling

adult at the present time may be strongly indicated.

But is there any evidence for this aforementioned idea and is there any merit in pursuing this topic at this time of such pressing health concerns? To answer these questions, this current review sought to examine whether hip fractures are still occurring at rates comparable to pre pandemic times, and if so, is there any heightened need for concern in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Information concerning whether there is a need for modified and carefully construed and delivered prevention approaches as well as subsequent treatments of these injuries that can be better targeted and tailored to restore optimal function and prevent further disability, given the pandemic, was also sought.

Method and Procedures

To fulfil the aims of this report, all pertinent full length published studies in the English language detailing the

impact of COVID-19 on hip fractures in the

Results

Among the relevant studies published to date, only a few countries have reported on this topic, including

China, Italy, France, United States, the United Kingdom, and Spain, even though most countries globally

have experienced high infection rates and house large cohorts of aging adults. Among these heterogeneous

reports, are small sample sized non-uniform descriptive studies, case studies, case reports, and several short

term, rather than long-term follow-up prospective studies, and limited numbers of comparative studies,

generally indicating that this body of information is only in its infancy.

As outlined in one current report [16], it appears safe to say however, that regardless of where the data were published, hip fracture patients admitted from the community are clearly a particularly vulnerable population of older adults who tend to have a higher mortality rate than the norm, especially if they are COVID-19 positive. In this report, which focused on a study examining the issue of hip fractures in Spanish hospitals where patients 65 years of age had recently presented to the Emergency Department of the participating hospitals with a diagnosis of proximal femoral fracture, the researchers found that of the 136 admitted cases, the total mortality rate was 9.6%, and 23/62 cases tested were positive for COVID 19. The mortality rate for these 23 patients was 30.4% (or 7/23 patient deaths) at a mean follow-up time of 14 days. On the other hand, the mortality rate was 10.3% (or 4/39) for patients with a negative test result and 2.7% (2/74) for patients who had not been tested. Of the 12 patients who were managed non-operatively, 8 (67%) died, whereas, of the 124 patients who were surgically treated, 5 (4%) died. Results differed among centers, but overall there was a higher mortality rate in patients with a hip fracture and an associated positive test for COVID-19 [17].

Egol et al. [18] who recently conducted a prospective study of seven facilities including 138 recent hip fracture cases and 115 older cases during the COVID-19 pandemic showed 12.2% of these patients were affected by the virus, and another 14 were suspected of having the virus. Those with a confirmed COVID diagnosis had an increased mortality rate, and length of hospital stay, plus a greater rate of major complications, and postoperative ventilator needs. The morbidity as well as mortality rates were clearly higher in cases with confirmed COVID-19 infections, and tentative fiscal costs although not assessed were potentially increased quite significantly due to the added surgical and post surgical needs.

Lebrun et al. [19] who similarly evaluated in-patient outcomes among hip fracture cases treated in different centers during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City found ten patients or 15% of cases tested positive for COVID-19 (COVID+), 40 or 68% tested negative, and 9 or 15% were not tested. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores were higher in the COVID+ group (p=0.04); however, even though the Charlson Comorbidity Index was similar between the study groups (p=0.63). Inpatient mortality was significantly increased in the COVID+ cohort (56% vs. 4%; p=0.001). Including the one presumed positive case in the COVID+ cohort increased this difference (60% vs. 2%; p<0.001). It was concluded that hip fracture patients with concomitant COVID-19 infection are likely to have worse anesthesia scores and significantly higher rates of in-patient mortality compared to those without any apparent COVID-19 infection.

Sharyati and Kachooei [20] who prospectively examined data on three patients with low energy fragility fractures of the hip and concomitant COVID-19 infection showed all patients were elderly and had fallen from a standing height. The most common symptoms were weakness and fatigue. According to the results, two patients underwent surgical treatment, and all underwent medical treatment for COVID-19 infection. The authors concluded that there is a possible relationship between COVID-19 infection and fragility fractures of the hip joint in elderly patients that could be induced by fatigue and weakness due to the disease. Thus attention to preventing COVID-19 may be especially relevant among those elderly who already suffer from frailty and hip joint osteoporosis. However, Cheung and Forsh [21] who conducted a retrospective study of 10 patients ≥60 years of age with a hip fracture and COVID-19 who underwent surgical treatment in New York City during the COVID-19 outbreak from March 1, 2020 to May 22, 2020 concluded that hip fracture patients who present with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19 infection can safely undergo early surgical intervention after appropriate medical optimization, but even here, Thaler et al. [22] note that surgery may not be readily available to all due to massive cutbacks for all types of surgeries even those due to prior massively failed joint arthroplasty surgeries, component failure or imminent dislocation, which are all possible falls and fracture determinants.

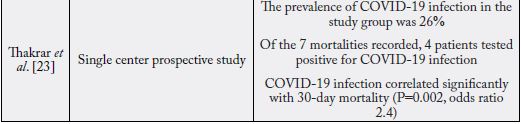

A further study conducted in the United Kingdom concerning the 30-day mortality rate of hip fracture cases during the COVID-19 pandemic [23] specifically showed that of the 43 patients studied, the 30-day mortality rate of the group with a COVID-19 infection diagnosis was 16.3%, which was higher than control non infected groups. The prevalence of COVID-19 infection in the study group was 26%, and of the seven mortalities recorded, four patients had previously tested positive for COVID-19 infection. Results further revealed that in the study group, the presence of a diagnosed COVID-19 infection correlated significantly with the patient’s 30-day mortality rate, which was found to be markedly increased.

To show that many hip fractures continue to occur in the home during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the nature of these, Zhu et al. [24] examined the epidemiologic characteristics of various traumatic fractures among 436 elderly patients admitted to a hospital in China. Among these cases who were approximately 76.2 years of age and where 72.7% had sustained their fractures at home, 264 or 58.3% were hip fracture cases. Falling from a standing height was the most common cause of fracture, findings that clearly stress the great importance of primary prevention (home based prevention) measures during this current global COVID-19 pandemic and widespread lockdowns. In this regard, Malik-Tabassum et al. [25] argue that the careful introduction of institutional adaptations to facilitate prompt treatment in hip fractures during this current pandemic is also clearly desirable and expected to produce more favorable outcomes than not.

In another study conducted during the early COVID-19 pandemic period as regards hip fractures Hall et al. [26] chose to both assess the independent influence of the coronavirus disease on the 30-day mortality of these patients, as well as to determine whether: 1) there were clinical predictors of COVID-19 status; and 2) whether social lockdown influenced the incidence and epidemiology of hip fractures. To this end, they reported on a national multicentre retrospective study conducted to include all patients presenting with a hip fracture to six trauma centers or units over a 46-day period (23 days pre- and 23 days post-lockdown). Results of 317 patients with acute hip fracture showed 27 or 8.5% had a positive COVID-19 test, even though only seven or cases had suggestive symptoms on admission. COVID-19-positive patients had a significantly lower 30-day survival compared to those without COVID-19. COVID-19 even when adjusting for: 1) age, sex, type of residence; 2) Nottingham Hip Fracture Score; and 3) anesthesia score. A similar number of patients presented with hip fracture in the 23 days pre-lockdown (n = 160) and 23 days postlockdown (n = 157) periods with no significant difference in patient demographics, residence, place of injury, Nottingham Hip Fracture Score, time to surgery or management. These findings were taken to imply a particular need for COVID-19 testing among hip fracture injured patients and that rates are not dropping even though one might expect fewer outdoor related falls.

In another study examining the effects of COVID-19 on perioperative morbidity and mortality in patients with hip fractures by Kayani et al. [27], COVID-19-positive patients were similarly found to have increased postoperative mortality rates of 30.5% vs 10.3% in COVID-19-negative patients. Risk factors for increased mortality in patients with COVID-19 undergoing surgery included positive smoking status and having greater than three comorbidities. COVID-19-positive patients also had an increased risk of postoperative complications, more critical care unit admissions, and an increased length of hospital stay (13.8 days vs 6.7 days) compared to COVID-19-negative patients. However, Catallani et al. [28] still argues in favor of surgery for cases with a proximal femoral neck fracture and COVID-19, because this still seems to benefit the hip fracture patient’s overall stability, seated mobilization, physiological ventilation, and general comfort in bed if they survive surgery.

No group mentioned the precise reasons for their findings as regards mortality and morbidity, and none reported on post hip fracture functional status and actual post-fracture outcomes and destination, however. Especially lacking was any inference to neurological manifestations, which include fatigue, myalgia, dizziness, and are highly prevalent in COVID-19 infected patients. Indeed, emerging clinical evidence suggests neurological involvement is an important, potentially overlooked, aspect of the disease that may account for hip fracture occurrences plus poor associated outcomes in some cases [29,30]. Other key factors associated with hip fractures are falls injuries, poor physical fitness or activity participation, comorbid health conditions including osteoporosis, depression, anxiety, and diabetes plus ineffective protective reflex responses and low muscle mass, but none of these are currently mentioned as noteworthy either among non COVID-19 patients or those with the infection.

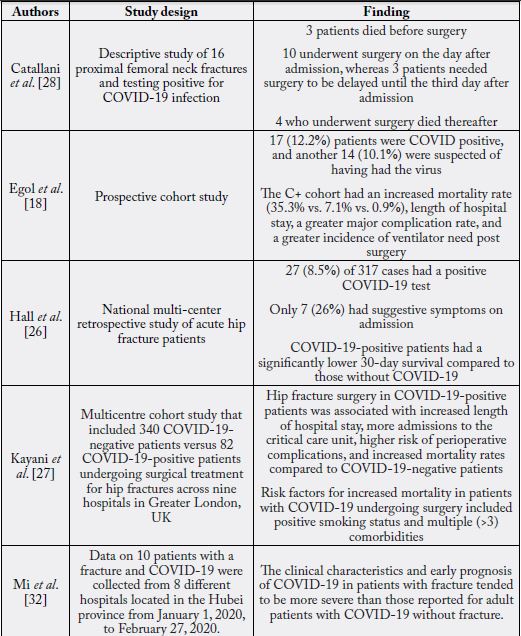

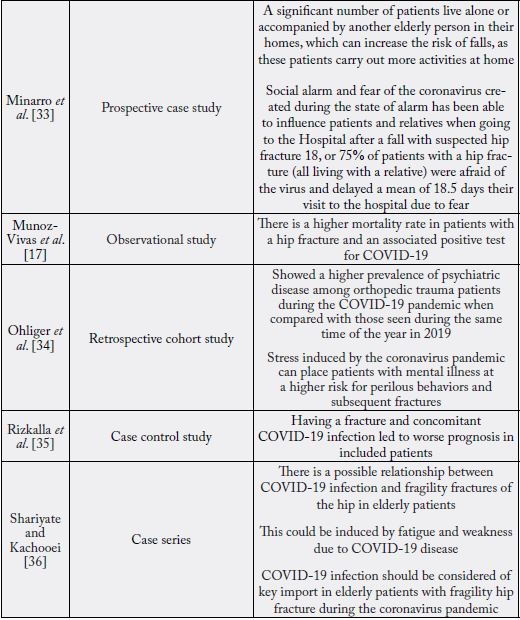

Consequently, as outlined by Ferrari et al. [31] while efforts to prevent hip fractures are currently based on regular physical activity; falls prevention; the correction of nutritional deficiencies, including vitamin D repletion; and pharmacological intervention, their current efficacy appears less than optimal, and unlike fractures at other sites, does not appear to offset the rates of hospital admissions observed during the current coronavirus pandemic to the degree anticipated. While it is possible that without these approaches, much more serious trauma and hip fracture injuries may have prevailed, it hard to envision not only precisely where the emphasis should now be placed to minimize hip fracture morbidity and mortality rates, and what -if any- hip fracture prevention approaches need to be modified in the context of hospital and personnel cutbacks, social isolation and restricted travel, among other factors. Clearly, to face the challenges observed to be presently associated with hip fractures among the older community dwelling adult, osteoporotic patients and others who are at high risk of hip fracture as well as COVID-10 may require highly focused care if they are to be optimally protected from a multitude of future costly outcomes predicted by the available data, and findings from multiple sites that have reported on hip fractures during the pandemic as per Table 1 below.

Discussion

Hip fracture injuries, one of the most serious public health problems facing aging nations, remain immense

challenges to health care systems worldwide, as well as to the many older adults who are frequently found to

sustain one or more of these injuries. At the same time, the current COVID-19 pandemic has placed many

older adults at risk not only for premature death or increased general morbidity, but for worse outcomes in the

cases shown in this review of hip fractures, sustained mostly in the home environment. Indeed, many elderly

currently isolated at home may not only have suffered large declines in general health, but may have acquired

this infectious disease unknowingly, despite precautions to avert it. As such, they may also have become even

more likely to fracture a bone such as the hip joint than those who have not acquired the infection, due to

associated weakness and fatigue correlates, among others. They may also be more reluctant to report having

sustained a possible fracture, as well fearful, of acquiring COVID-19 in the hospital environment

Indeed, while the research concerning this present topic is rudimentary at best, as outlined in Table 1, the current results are quite uniform and compelling and indicate little argument that hip fractures remain highly relevant causes of excess deaths and morbidity among older community dwelling adults in the midst of this global pandemic. At the same time, efforts to offset hip fracture risk in the community among older adults have been seriously curtailed, older adults may not want to leave the house even if these programs are accessible, helpers may not want to interact with older ‘at risk’ adults, and fears about COVID-19 may deter the older adult from seeking professional help and testing or both.

Although a vaccine is thought to be pending in some distant time, the current hardships of lock downs, fears, falls, social isolation, diminished services, and poor health amidst the viral risk appears to have created a perfect storm as far as hip fracture incidence and severity, plus immense additional public health costs, that are generally unlikely to abate, anywhere, any time soon. The nature of any ensuing complications, second hip fractures, pain, cognitions are also relatively unknown, but could be costly as well.

As such, and based on what we have currently learned, and the fact there is no time or even opportunity to safely conduct robust clinical efficacy associated studies or others, and that many reasonably helpful preventive and intervention strategies that have begun to partially minimize hip fracture debility and death rates may need to be scrapped, or put ‘on hold’, a more intense focused tailored and holistic approach rather than a generic approach is indicated. Themes that emerge from the current data of particular importance in this regard include preventing frailty, fragility, and muscle weakness, while reducing excess fears and depression. More attention to home safety issues, stress reduction, sleep hygiene and nutrition is also potentially indicated, both generally, as well as post-fracture to avert further decompensation and enhance functional recovery. As per Jain et al. [37] contingency plans in these times may need to be specifically targeted for those with osteoporotic hip fractures, a highly vulnerable group.

In terms of research that would be helpful currently and seems doable, collecting more practice based and outcome data in more centers on this theme will likely be most helpful clinically in establishing and solidifying key trends that can be applied towards the development of sound critical treatment and prevention pathways. As well, especially helpful, if these are possible to conduct, will be long-term follow up studies of current survivors and detailed regression analyses to tease out determinants of optimal survival. Better documentation of possible hip fracture antecedents in individual cases in all forthcoming reports is especially indicated here.

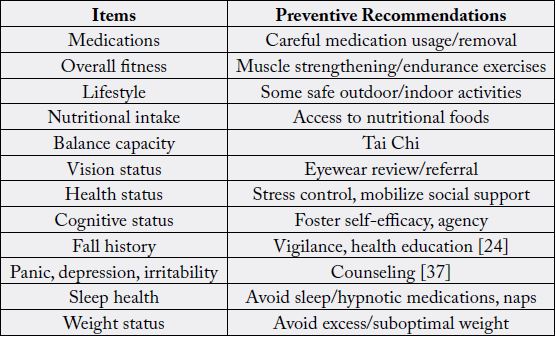

In the meantime, Beaupre et al. [38] appear to have proposed possible assessment approaches that appear worthy of consideration on a routine basis at this time, and that may lead to frameworks that can help foster more tailored and of targeted preventive strategies against hip fractures for a specific community dwelling adult as well as for preventing COVID-19 virus exposure directly, or as a result of a debilitating injury or visit to an emergency room or other hospital venues. These include, but are not limited to screening high risk adults for several risk factors that may underpin both health issues in some way and encouraging and supporting community dwelling elders to carry out appropriate self-management strategies where applicable via well designed health education approaches [24] [see Table 2].

In essence and in recognition of the growing public health problem of osteoporosis and fragility fractures that prevail among the older population, including hip fractures and their management which has been hampered by lockdowns and other infection prevention transmission strategies used to contain the COVID-19 pandemic [39], as outlined some time ago by Wilson and Wallace [10], it appears that to reduce the burden of hip fractures among older members of society continued vigilance in designing primary and secondary prevention that can be conducted in the home environment is needed now more than ever.

By contrast, and bearing in mind the multi-factorial origin of hip fractures, and that those older adults with multiple comorbid health conditions, and who are now socially isolated may be more vulnerable than ever, an exaggerated excess burden of multiple negative costs and outcomes can be anticipated to emerge for some time to come if no concerted effort to counter this situation is forthcoming. Indeed, as discussed by Jain et al. [37], recent studies have shown that elderly patients with fractures associated with medical comorbidities such as diabetes, and hypertension are not only more severely affected by COVID-19 infections, due to their reduced functional reserves and weakened immune systems, but to hip fracture injuries with higher mortality rates than those older adults with no apparent coronavirus infection.

In this regard, since many at risk older adults residing in the community may currently have no access to direct contact with health care personnel on a consistent basis, and may not be able to employ remote methods effectively, helpers may need to be creative in their efforts to ensure these older adults do not lose muscle function and mass, which in turn, has a profound influence on bone quality and integrity. Physical activity, also key to preventing of chronic diseases, increasingly related to hip fracture injuries as well as COVID-19 such as diabetes and osteoporosis is also strongly encouraged. In addition, attention to fostering optimal cognitive status must also be considered of import here. As well, encouraging safe outdoor activities such as walking that exposes older people to vitamin D and enables them to weight bear in variable contexts, may further facilitate efforts to maintain optimal neuromuscular reflex function as well as bone structure. To further prevent hip fracture disability and enhance hip fracture surgical outcomes, high intensity strengthening and balance related exercises, plus activities that promote early weight bearing after surgery, and prolonged follow-up strategies are also strongly indicated to maximize functional independence and to reduce the onset of depression, excessive drug use, and risk of incurring a second hip fracture. To specifically reduce hip fracture morbidity and mortality rates associated with second hip fracture, those with comorbid conditions, cognitive disorders, as well as those using psychotropic drugs should be especially targeted. Also noted by Battacharyya [40] we should not discount the importance of comprehensive osteoporosis care to reduce fragility fractures and keep the elderly patient out of the hospital system during the prevailing 2020 coronavirus pandemic.

Conclusion

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, older adults who sustained hip fracture injuries and were admitted early

on into any sort of dedicated orthogeriatric ward, appeared to have a reduced long-term mortality rates when

compared to those who did not have this opportunity [41]. However, this optimally efficacious approach to

treatment of these debilitating hip fractures among the elderly may not be universally possible during the

current COVID-19 pandemic where surgery may not be possible, and where length of stay and intensive

rehabilitation post surgery is likely to be minimized or severely curtailed, and some admitted cases are

already suffering from the oftentimes debilitating COVID-19 disease.

In essence, although rates of hip fractures among the elderly appear similar to those of the preceding year, a high percentage of elderly cases who currently experience hip fracture injuries may either enter the hospital with a COVID-19 infection, or may have undetected COVID-19 infections, which predict a worse hip fracture outcome than not, regardless of intervention mode.

On the other hand, while hip fracture rates may not have increased overtly during the pandemic, since not all cases have been carefully examined to date, and missing cases may be common among those unable or too fearful to enter the hospital system despite a clear injury, the increased demands placed on hospitals has surely increased the human and fiscal costs of this potentially preventable injury. Moreover, a dramatic surge in fractures and related mortality is anticipated due to fragility and poor bone health as well in the very near future [42].

To minimize these predicable human costs and others, public health interventions focusing on encouraging moderate safe forms of physical activity participation and exercises that promote muscle strength among all community dwelling younger and older adults, regardless of health status, are hence strongly recommended. High risk adults in the community, especially those with comorbid diseases and/or a low body mass should be especially targeted [43].

To avert any excess mortality and morbidity in the future, it is clear studies to examine factors affecting current surgical outcomes and whether targeted and tailored health care interventions for older individuals with a high risk profile for falls and fractures, as well as viral infections living in the community are efficacious, along with health services evaluations [44] are strongly indicated.

In the interim, regardless of the absence of any clear contemporary evidence based research in this realm, the available practice based evidence base depicted here and summarized very ably by Jain et al. [37], clearly shows that securing the optimal health of the community dwelling older adult in an era of limited services, travel opportunities, and therapy clinics, as well as secondary prevention and ongoing rehabilitation is of paramount importance in the context of averting excess mortality and morbidity and immense social costs attributable to hip fractures and COVID-19 among the older population. Alternately, delayed, improper or no intervention, challenges of remote interventions, and others are likely to result in immense unanticipated complications [45], especially in light of evidence that several specific high risk pre-existing co-morbidities such as falls histories and fragility fractures and comorbid diseases are clearly associated with COVID-19 hospitalizations and related deaths in community based older men and women [46].

As discussed by Lui et al. [47], it appears especially important to presently keep older isolated adults as healthy as possible, because even if available surgical treatments of hip fractures in the elderly can enhance fracture recovery, the added risk of a parallel COVID-19 infection, plus weakness, and fever, among other factors, may greatly interfere with incision healing, as well as postoperative rehabilitation processes. Furthermore, a recent study indicated that surgical stress may actually activate or aggravate the progression and mortality of COVID-19 [9]. Thus preventing home based falls and others that often lead to hip fractures, as well as other modifiable risk factors for this debilitating condition appears of high relevance to address at the primary prevention level, as well as the tertiary level at the present time. Indeed, providers at all levels are urged to comprehensively analyze each older adult’s situation in order to create the most favorable preventive plan for the individual in the home, as well as when being discharged to the home post surgery.

Factors warranting high attention in efforts to keep older community dwelling adults safe before and after hip fracture injuries as based on the literature are listed below.

• Balance/ moderate strengthening exercises

• Medication checks

• Environmental safety checks and hazard removal

• Optimal nutrition

• Optimal sleep duration

• Osteoporosis prevention

• Preventing influenza type infections

• Reducing/eliminating smoking/excess alcohol use

• Use of anti-slip shoe devices/assistive device usage

• Vision devices/regular eye checks

• Vitamin D* and calcium supplementation [38,39,44,48-50] *for bone + COVID-19 effects [49]

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!