Biography

Interests

Lungisani Mkandla, Eberhard Tapera, M.* & Morris Banda

National University of Science and Technology, Department of Sports Science and Coaching, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

*Correspondence to: Dr. Eberhard Tapera, M., National University of Science and Technology, Department of Sports Science and Coaching, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe.

Copyright © 2019 Dr. Eberhard Tapera, M., et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

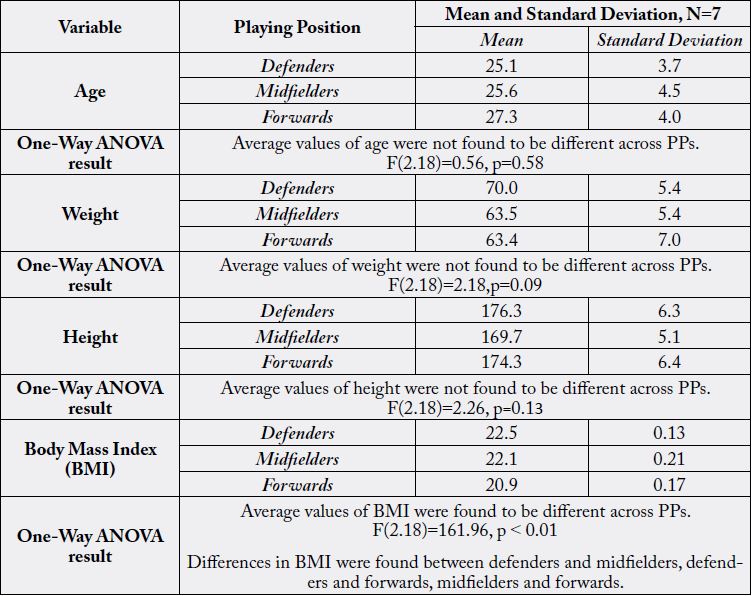

Age, weight and height and body mass index (BMI) are very important attributes in soccer. The aim of this study was to determine the age, weight, height and BMI of Zimbabwe male league soccer players, and compare these variables across playing positions (PPs). Twenty-two (22) players (ages 21-33 years) volunteered to participate in the study and were categorized into PPs, defenders (n=7), midfielders (n=7) and forwards (n=7). Age was computed from dates of births obtained from team records, while height and weight were determined using standard ISAK proptocols. BMI was derived from the weight and height values measured. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) were used to present the data for each position. A One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the data (at p=0.05) to determine any significant differences in the selected variables by PP. A Newman-Keuls post-hoc was also performed, also at p=0.05, to locate the PPs across which any significant differences existed in each attribute. The study found no significant differences in age, weight, and height across PP, but found significant differences between defenders and midfielders, defenders and forwards and midfielders and forwards. It is recommended from the study that Zimbabwe male league soccer players be selected on the basis of age, weight, height for the different roles they play as defenders midfielders and forwards in soccer. It is further recommended that male league soccer players be given position-specific training to attain homogeneous BMI which is desirable in top-flight soccer .These recommendations are meant to enable Zimbabwean soccer players to function effectively in the different demands imposed on defenders midfielders and forwards.

Background

Soccer, also known as football, is the most popular team sport in Zimbabwe and the world [1,2]. It is

characterized by high intensity, short term actions and pauses of varying lengths. The sport comprises of

sprints, jumps, change of direction, among other movements. It is practiced socially and professionally by

many segments of the population. Several studies have been done on anthropometric and physiological

profiles of elite soccer players in the America and Europe (Ostojic, 2002) [3,4]. Few such studies have

been done in Africa. Clark (2007) [5] observes that positional roles are less well distinguished on the basis

of physical fitness in Africa. Knowledge of age and anthropometric attributes of players is of paramount

importance to coaches, trainers, players, educators and physiotherapists among countless others in order

to effect sound interventions in sports. It appears logical that if the main physical features , among other

variables that influence player performance in soccer can be identified then they can be nurtured to yield

success. (Bangsbo, 1994) made the observation that soccer is not a science but science may help improve

performance in soccer. Assessment of physical capacities of athletes is a very important issue in modern

sport. Numerous tests are available for selection procedures, for screening candidates or to monitor the

efficacy of (sports) training regimes [6].

There is scarce scientific literature on anthropometric of soccer players in Zimbabwe in particular, and Africa in general.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate age, weight, height and BMI of male soccer league players in

Zimbabwe, using Bulawayo Chiefs Football Club as a case study. The research sought first, to determine

age, weight, height and BMI of Zimbabwean soccer players, and second, to compare the variables by playing

position (PP).

The study hypothesized that there will be significant differences in age, weight, height and BMI, of male

league Zimbabwean soccer players by PP.

Results of the study are expected to:

a) provide information for the coaches so that they can better plan and improve the training program and

help the players to enhance their performance.

b) help in the screening and selection of soccer players for specific positions in soccer

c) assigning of relevant tasks that match their anthropometric characteristics

d) provide baseline data upon which future related studies can refer to, and,

e) enhance the formulation of sound training strategies that will improve sports performance.

Bulawayo Chiefs Football Club was involved in the competitive Premier Soccer League during the time of

the study. It was consequently difficult to test them as many times as the researchers would have wanted. The

small sample size, n=22, was another limiting factor. Consequently there was only one goalkeeper available

in the limited sample which made comparison of that PP impossible.

The study was delimited to one team, Bulawayo Chiefs Football Club and male soccer players who were

involved in the First Division soccer during the research. The study was further restricted to the variables

age, weight, height and BMI, and the PPs defenders, midfielders and forwards.

Literature Review

This chapter contains a review of literature related to the topic under study. The review highlighted the main

anthropometric and physiological variables needed for soccer competition.

Soccer is the most popular sport in the world. It is played by males and females of different ages, race or

ethnicity at varying levels of expertise [12]. There is limited scientific information pertaining to age and

anthropometric performance parameters in Zimbabwe. Playing football requires specific anthropometric

and other characteristics, besides skill, experience and intelligence [13,14]. Soccer is an invasive team sport

lasting a minimum of 90 minutes and characterized by intermittent regimens of effort [15].

Successful competition in sports has been associated with specific anthropometric characteristics, body

composition and somatotype (Carter and Heath, 1990) [16]. Norton et al., (1996) [17] echoed that physical

traits are acknowledged as having an influence on competitive success in many sports…with anthropometric

variables such as height, body mass and body type being very important.

Soccer performance has been shown to decrease with age though there are some positions where experience

matters most, and the reverse is true. Reilly (1996) [15] stated that world class soccer players tend to have an

average of 26-27 years with a standard deviation of about 2 years. Bangsbo and Reilly (1994) further state

that the average age of goalkeepers were higher than other positions in the team.

Height, also called stretch stature, is the perpendicular distance between the transverse planes of the vertex

and the inferior aspect of the feet [18]. It is the vertical measurement from heel to top of the head of the

human body [19]. Soccer players should be assigned playing positions considering their height, for optimal

performance. Height bestows an advantage to the goalkeeper, centre-backs and to the forward used as the

target man for winning possession of the ball through heading (Reilly et al, 1990). A good height has an

influence in sports performance especially in cases where players such forwards need to head shots to score

goals, and on defenders and goalkeepers who need to deal defensively with aerial balls.

Bloomfield et al., (2005) found that the average heights of elite male soccer players from the Bundesliga and La Liga to be 1.83±0.06m and 1.80±0.06m, respectively. That indicated that the height of most European based soccer players from successful countries such as Croatia, Germany, Spain, Portugal, England, Denmark and many more is within that range. Therefore, it appears that there is an optimal height for successful soccer performance.

Reilly et al., (2000) [1] state that there are likely to be anthropometric predispositions for positional roles with taller players being most suitable for central defensive positions and being target players among the strikers or forwards. Bloomfield et al., (2003) conducted a study on European soccer players and concluded that variations in height and body mass between players in different leagues suggested that the styles of football might vary with teams from different leagues preferring different types of players in certain positions.

Body weight is described as the mass of an organism’s body [19]. Anthropometric studies show that certain

physical factors including body fat, body mass, muscle mass and physique significantly influence athletic

performance [20]. In addition, Chin et al., (1994) report that low percentage body fat would generate higher

forces for jumping, kicking and tackling. Too much weight tends to inhibit sports performance. Reilly

(1990) stated that during running, jumping and direction changes, players must move their own body mass,

which makes a high body fat content appear to be a disadvantage in soccer. Ekblom (1990) adding to

the observation, states that an excess body fat acts as dead mass in activities where body mass is lifted

repeatedly against gravity in running and jumping during play. Reilly and Secher (1990) further concur to

that, indicating that body composition plays an important role in physical fitness of soccer players and that

excess mass in form of fat may be detrimental to players’ performance. Reilly (1990) reported an overall

mean body mass of 74.0±1.6kg for nine English professional squads.

Inappropriate body weight, BMI, related waist sizes and body shape are reported to be factors suggestive

of excess weight [21]. Matkovic et al., (1993) found BMIs of 24.16kg/m2 for Croatian first division soccer

players, while Bangsbo et al., (1991) found 23.87kg/m2 for their Danish counterparts. Casajus (2001) [22]

on the other hand found BMI values of 24.34kg/m2 for Spanish first division soccer players, while Helgerud

et al., (2001) found BMI values of 23.18kg/m2 for Norwegian soccer players in the same division. Sutton et

al., (2009) [23] states that the body composition is important for elite English footballers, but also observes

that homogeneity between players at top professional clubs results in little variation (in BMI) between

individuals (Brackets ours). Previous research on BMI acknowledges that immoderate body fat is a highrisk

factor, and relates injury to increased BMI, leading to the exposure of athletes to a multitude of other

risk factors, a finding which requires further examination of the association between being overweight and

sports injury [24,25].

Research Methodology

This chapter describes the research design, population, sampling method, sample size and the data collection

protocols used for the study.

The study used a quantitative descriptive cross-sectional research design. The researcher measured the age,

weight, height and BMI once during the 2017-2018 soccer season. The design selected is shorter compared

to other designs like case studies, longitudinal designs or ethnographic designs.

The population available to the research team included all the teams in the Zimbabwe Premier Soccer

League. Purposive sampling was used to select a sample of 22 players from Bulawayo Chiefs Football Club players aged 21-33 years who voluntarily agreed to participate in this study.

The subjects were fully informed of the procedures, potential risks and the benefits of participating in the study, after which they consented to take part in the research by signing consent forms. The subjects were then familiarized with the testing procedures one week before the collection of data.

The researcher used lecturers and fourth year students from the National University of Science and

Technology Department of Sports Science as research assistants to collect data on the anthropometric

variables under investigation.

The researchers sought permission from the authorities of the club authorities, players and the National

University of Science and Technology. All the subjects gave their informed consent prior to the commencement

of the study. All the details of the participants were managed in coded from in a private and restricted access.

Acknowledgements were made upon completion of the research, to appreciate all the contributions rendered

for the completion of the study.

Quantitative data were collected on age and the anthropometric variables height (stretch stature), body mass

(weight) from which body mass index (BMI) was derived.

One reason for testing is to assign positions and ranking. All the coaches want to be sure they are putting

their best athletes, at their best positions, in any game [26]. Testing provides a way of establishing the

potential of an athlete and the basis for performance evaluation. All the participants performed a 10-minute

warm up, which included jogging, sprinting, multi-directional movements and stretching. The players were

exempted from strenuous exercise 24 hours before testing to minimize the possible effects of fatigue. All

the participants were assessed in 1 days, in the morning. The tests were done in the same order, namely

age, weight, height and derivation of BMI. Field tests were used instead of laboratory tests. Field tests are

relatively are easy to administer, require no sophisticated equipment and expert and have higher ecological

validity over laboratory tests [27].

The tests battery included determination of age, and measures of weight, stretch stature (height), and derivation

of BMI.

Age was determined by extracting dates of birth from team records.

Anthropometric measurements were measured following the standard protocol of the International Society

for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (ISAK) as follows:

Height is a perpendicular distance between the transverse planes of the vertex and the inferior aspect of the

feet [18]. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1cm using a stadiometer.

Body mass is the quantity of matter in a body and is calculated through the measurement of weight. Body

mass was measured to the nearest 0,1kg using analogue or digital scale.

Body mass index (BMI) is the relative amount of fat, muscle, bone and other vital parts of the body. Moreover,

it is a measure of relative weight based on an individual’s mass and height. It is computed by dividing the

individual’s body mass by the square of their height, and is expressed in units of kg/m2 [28].

“Reliability of measurement refers to the degree to which the test yield the same result when given on two

[or more] different occasions or by the different examiners to the same group of individuals” [29]. A test

must be reliable which has been defined as, “the consistency of an individual’s performance on a test” [30].

“Validity constitutes the degree to which an instrument measures what it is purported to measure and the

extent to which it fulfills its purpose” [29].

The reliability and validity of the results was assured as the researcher used approved a battery of field based tests which were done by qualified personnel using standard and well calibrated instruments.

The data obtained were analyzed using descriptive and comparative statistics computed using Statistical

Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Version 20.0). The results were expressed as mean and standard deviation

for each variable. Differences in age, weight, height and BMI across PPs (defender, midfielder, forward) and

country were determined by using One Way Analysis of variance (ANOVA), with at the p=0.05 significance

level. A Newman Keuls post-hoc (at p p=0.05) was further performed on the data to locate the specific positions

across which differences in age, weight, height and BMI existed

Data Presentation, Analysis and Interpretation

Discussion

The average age of the Zimbabwean soccer players was found to be equal across PP. This homogeneity in

age contrasts research (Bangsbo and Reilly, 1994) which states that the average age of goalkeepers (and defenders)

were higher than other positions in the team. There should be differences within a soccer team in

ages of players in terms of PP as some positions such as goalkeeping and defending require more experience

than others. Stabilizing the defense with more experienced (older) players will allow coaches to experiment with numerous combinations of young play upfront. The players who can be gradually introduced are usually

midfielders and strikers. Such a mix blends youth with experience ensures continued stability in soccer teams

and augurs well for the continued success of the teams.

There were no significant differences in weight across the Zimbabwean soccer players by PP. Reilly (2000)

[1] however emphasizes that elite soccer players are characterized by relative heterogeneity in body size.

This heterogeneity will allow players to fulfil their different expectations according to their position in

soccer. Some players such as defenders and strikers need to contest for the ball defensively and offensively,

functions in which high body weight is an advantage. Zimbabwe male league soccer players are therefore

disadvantaged by their similarity in weight across PP.

Zimbabwean soccer plays showed no difference in height across PP. However there should be differences in

height in terms of playing positions within a team as the positional demands vary. Reilly et al (1996) [15]

propounds that height does bestow an advantage to the goalkeeper, centre backs and to the forward used

as the target man for winning the possession of the ball with his head. Taller defenders and strikers tend to

have an advantage in defensive or offensive heading in front of goal. The homogeneity of male league Zimbabwe

players thus compromises the performance of defenders in their defending and forwards in terms of

ball possession.

Average values of BMI were found to be different across PPs, F (2.18) =161.96, p < .01 Differences in BMI

were found between defenders and midfielders, defenders and forwards, midfielders and forwards. This finding

suggests heterogeneity in male Zimbabwe soccer players across PP. Sutton et al., (2009) [23] however

observes that homogeneity between players at top professional clubs results in little variation (in BMI) between

individuals. Zimbabwe soccer players thus need to intensify training to moderate their position -different

BMI in order to be able to perform their roles when they compete with professional teams [31-67].

Summary, Conclusions and Recommendations

The aim of this study was to determine the age, weight, height and BMI of Zimbabwe male league soccer

players and compare these variables across PPs defenders, midfielders and forwards.

Age was computed from dates of birth supplied by the team record, while height and weight were determined

using standard ISAK proptocols. BMI was derived from the weight and height values measured. A

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the data (at p=0.05) to determine any significant differences in the selected variables by PP. A Newman-Keuls post-hoc was also performed, also at p=0.05,

to locate the PPs across which any significant differences existed in each attribute studied.

The study found no significant differences in age, weight, and height across PP, but found significant

differences between defenders and midfielders, defenders and forwards and midfielders and forwards at the

p=0.05 level of significance.

Male league Zimbabwe soccer players have similar age, weight and height but different BMI.

Zimbabwean league soccer coaches for men’s teams are advised to assign playing positions to players based

on age, weight and height demanded by the varying requirements of the positions in the game. Zimbabwean

male league soccer players should, further to that, undergo special weight-shedding training in order to

attain similar BMI values across PP, a feature which characterizes professional soccer. Future related studies

could consider drawing participants from a wider spectrum of soccer teams in the country and include

goalkeepers in the plaing positions investigated.

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!