Biography

Interests

Adnan Yousef Atoum1* & Mohmad Ihbeis Al Shalalfeh2

1Counseling and Educational Psychology Department, Yarmouk University, Jordan

2The Ministry of Education, Russeifa, Jordan

*Correspondence to: Dr. Adnan Yousef Atoum, Counseling and Educational Psychology Department, Yarmouk University, Jordan.

Copyright © 2018 Dr. Adnan Yousef Atoum, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

The Purpose of this study was to identify the level of Academic motivation and school engagement among high-primary school students in light of gender and the grade level, and identifying the predictive ability of academic motivation in school Engagement. To achieve the aim of the study, 929 students chosen randomly from high-primary school, and two scales were developed to measure academic motivation and school engagement. The results showed that the overall scores for academic motivation and school Engagement were higher for males and the higher-grade levels. Finally, the results showed a significant predictive ability of academic motivation for school engagement among school students.

Introduction

Academic motivation plays an important role in education and learning as it is associated with achievement

and increases students’ commitment to school activities [1]. High level of academic motivation among

students coincides with the increase in the students’ desire to knowledge and engage in activities related to

tasks and learning [2].

Academic motivation defined as an internal process that promote the continuity of activities aimed at achieving specific academic objectives [3]. Academic motivation refers also to increased desire, perseverance, and attention to academic materials in the student field to achieve competence [4].

Based on Rayn & Deci (2000) [5], academic motivation can be classified into three main categories: external motivation, internal motivation and a motivation. Internal motivation is when students do things for purpose of desire and satisfaction [6]. External motivation used when students do things for getting external rewards whether financial or psychological from parents or teachers. Finally, a motivation refers to the absence of a contingency between actions and outcomes, or students do not have specific purposes or goals and they do not seem to demonstrate the intent to engage in any activities [7].

Also, based on Amrai, Motlagh, Zalani & Parhon, (2011) [8], academic motivation includes three main dimensions: beliefs, goals, and intrinsic Vs extrinsic motivation. Beliefs refer to the individual’s personal ability to accomplish tasks. Goals reflect students turning to the task engagement and when students invest their efforts to obtain knowledge. Intrinsic motivation refers to the possession of sufficient internal motives to achieve the tasks required of them without any external influence, while external motivation refers to the processes where students can achieve their goals solely based on rewards and avoiding punishment.

School engagement is another factor related to students’ motivation and achievement. It is defined as a high effort and excitement students’ show toward their education, which reflects on students’ abilities to face challenges they meet by using effective strategies to overcome these obstacles [9]. School engagement is also known by the level of students’ participation in school activities within and outside the classroom that lead to success and achieving learning objectives [10].

School engagement is one of the important issues related to schools, since it influences students’ attitudes toward the school activities and increases the possibility of achieving educational objectives, learning outcome, and improves interaction with all elements of the school. Also, engagement affect the students’ ability to face problems and adjust well to school environment [11,10]. Lack of engagement in school activities is highly related to many problems such as personality disorders and school dropout [12].

School engagement is also an important tool through which students develop positive feelings with their peers, teachers, and the school environment. It gives students a sense of cohesion, persistent, and increased self-confidence and a positive identity [13]. Based on Fredricks, Bluemenfel & Paris (2004) [14], school engagement includes three main dimensions: cognitive engagement, behavioral engagement and emotional engagement. cognitive engagement refers to students’ investment in their efforts to obtain knowledge, while behavior engagement adheres to standards of conduct such as attendance and involvement in the classes [13]. Emotional engagement refers to the emotional reactions of students, whether positive or negative, in the classroom including the students’ sense of the importance of things [15].

Few studies explored the relationship between academic motivation and school engagement. Some studies indicated a statistically positive relationship between increased student academic motivation and increased school engagement [16-19]. Some studies indicated differences in school Engagement due to different levels of academic motivation [20], however, no studies focused on predicting school engagement though academic motivation.

The results of several studies indicated differences in the level of academic motivation in schools in favor of females [21-23], while few studies have noted that there are gender differences in the level of academic motivation in favor of males [24]. Some studies indicated that there are gender differences in the level of school engagement in favor of females [1,25,26]. Some studies indicated that the engagement of younger students’ is higher than the older students’ [27], while Martin (2012) [20] indicated that higher age students’ have higher levels of school engagement and academic motivation.

Researchers have notices that students with high academic motivations often are active in school activities in

general. Therefore, the present study hypothesized that academic motivation can influence school engagement

through its affective and positive attitudes toward school and its activities, and eventually can affect students’

outcome and performance. The current research sought to achieve a deeper understanding of the nature of

the relationship between academic motivation and school engagement, as well as to determine the extent to

which academic motivation and its dimensions (internal motivation, external motivation and amotivation)

can predict school engagement. In addition, the study explored differences in academic motivation and

school engagement due to students’ grade and gender.

Based on the above objectives, the current research attempted to answer the following questions:

1- Does academic motivation differ according to students’ grade and gender?

2- Does school engagement differ according to students’ grade and gender?

3- Can academic motivation and its dimensions predict students’ school engagement?

Some studies have explored the relationship between academic motivation and school engagement in various

setting but these results did not focus on the predictive ability of academic motivation on school engagement

[16-19]. In addition, researchers did not find any studies that addressed this relationship in Jordan or the

Arabic region since research focused mainly on motivation in general or achievement motivation individually.

The researchers believe that this research will make a significant contribution to the educational perspective in the region in term of understanding how academic motivation can help solve many problems our school face such as school violence, behavioral problems, and low achievement levels.

Academic motivation is defined as an internal and external state of an enthusiasm, happiness in performing

tasks required, and continuing to perform in order to achieve specific academic goals to reach the state of

cognitive balance [28].

School engagement is defined as the interest and desire to invest effort in order to gain knowledge and skills through complying with the rules of the classroom, initiating questions and dialogue with others, participating in social and sports activities and participating in school governance and administration [1].

Material and Methods

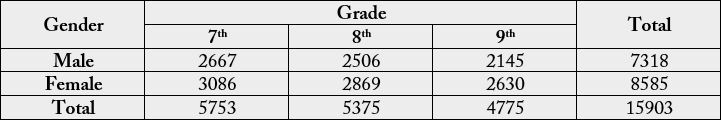

The study population consists of students in the seventh, eighth and ninth grades in Al-Rusaifa area-Jordan,

with total of (15903) students enrolled in public schools in the first semester of the academic year 2016/2017.

Table (1) shows the distribution of study population according to gender and grade variables.

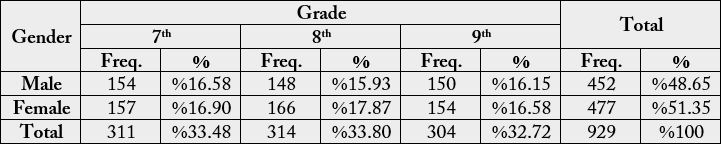

The sample of the study was chosen by a random stratified method based on gender and grade. The sample

consisted of (7%) of the study population. The researchers have chosen (929) male and female students.

Table (2) shows the distribution of the study sample according to gender and grade.

To gather data for academic motivation, the researchers reviewed previous studies and scales and Abdul-

Aziz (2015) [29] scale was chosen because it was appropriate for the age of students in the current study

and for its purposes as well. It consisted of 24 self-report items using 5-point Likert-type responses that

range from (always, often, sometimes, rarely, to never). The items were distributed into Sixth dimensions

each containing (4) items (knowledge, excitement, achievement, external organization, unconscious

organization and defined organization).

The scale was presented to a panel of 8 psychologists who volunteered to judge the scale in term of goals,

dimensions and language. Based on the request of 75% of the judges, some items were modified. To ensure

construct validity of the scale, the scale was distributed to a sample of 35 students. Correlations between

item scores and subscales scores were calculated. These correlations ranged between .30 to .67, which

indicate a good, construct validity of the scale.

To ensure the reliability of the scale, the researchers used data from the validity sample and Cronbach’s

alpha for internal consistency was calculated. Cronbach values for domains ranged from .48 to .78 and .84

for the whole scale. These results were considered good indicators of reliability of this scale.

To gather data for school engagements, the researchers reviewed previous studies and scales, and Tarabiah

(2016) [30] scale was chosen because it was appropriate for the age of students and for purposes of current

study. It consisted of 27 self-report items using 5-point Likert-type responses that range from (always, often,

sometimes, rarely, to never). The items were distributed into three dimensions (Behavior Engagement = 8,

Emotional Engagement = 8, Cognitive Engagement = 11).

The scale was presented to a panel of 8 psychologists who volunteered to judge the scale in term of goals,

dimensions, and language. Based on the request of 75% of the judges, some items were modified. To ensure

construct validity of the scale, the scale was distributed to a sample of 35 students. Correlations between

item scores and subscales scores were calculated. These correlations ranged between (.24 to .67) that indicate

a good construct validity of the scale, except items (7, 10 and 12), which were not significant and their

correlations were below .3 therefore, they were deleted.

To ensure the reliability of the scale, the researchers used data from the validity sample and Cronbach’s alpha

for internal consistency was calculated. Cronbach values for the domains ranged from .70 to .89 and .93 for

the whole scale. These values were considered good indicators of reliability of this scale.

Results

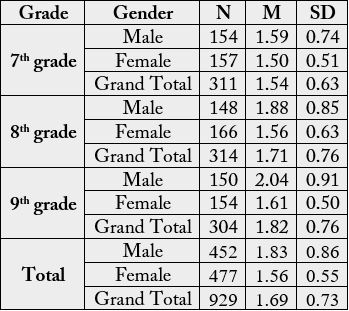

To answer the first question “Does academic motivation differ according to students’ grade and gender?”,

means and standard deviations for academic motivation total scores based on grade and gender were

calculated and shown in Table 3.

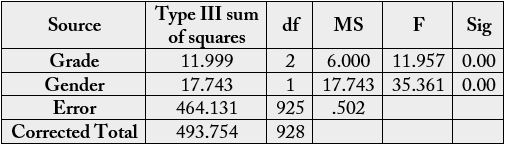

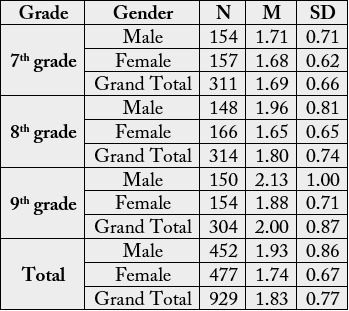

Results of Table 3 shows that there are apparent differences between the means among the overall score of academic motivation according to students’ grade and gender. To detect statistical significance of these differences, Two-way ANOVA was used, as shown in Table 4.

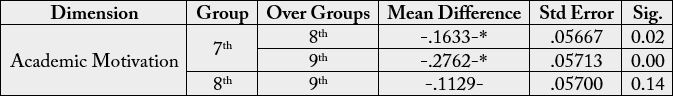

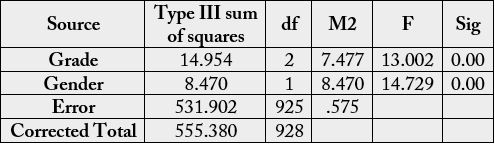

Results of Table 4 shows that there are significant differences at the level of α ≤ .05 due to Gender on the overall score of academic motivation and the difference was in favor of males (m = 1.82) compared to females (m = 1.56). Results of Table 4 also shows that there are significant differences at the level of α ≤ .05 due to Grade on the overall score of academic motivation. Post-hoc multiple comparisons using Scheffe Test to detect the effect of grade in academic motivation as shown in table 5.

Table 5. shows that the higher grade was the higher level in academic motivation. Significant differences were shown between eight and seven in favor of eight and between grade seven and nine in favor of grade nine.

To answer the second question “Does school engagement differ according to students’ grade and gender?”, means and standard deviations for school engagement total scores for the study sample were calculated and shown in Table 6.

Results of Table 6 shows that there are apparent differences between the means among the overall score of school engagement according to grade and gender. To detect statistical significance of these differences, Two-way ANOVA was used, as shown in Table 7.

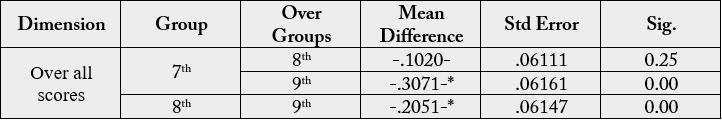

Results of Table 7 shows that there are significant differences at the level of α ≤ .05 due to students’ gender on the overall score of school engagement and the difference was in favor of males (m = 1.93) compared to females (m = 1.74). Results of Table 7 also shows that there are significant differences at the level of α ≤ .05 due to students’ grade on the overall score of school engagement. Post-hoc multiple comparisons using Scheffe was used to detect the effect of grade on school engagement as shown in table 8.

Table 8 shows that the higher the grade, the higher level of school engagement. Significant differences were found between students in seventh grade and ninth grade in favor of ninth grade and differences were found between students in eighth grade and ninth grade in favor of the ninth grade.

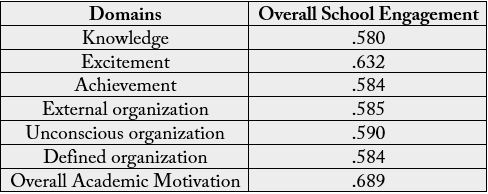

To answer the third question “Can academic motivation and its dimensions predict students’ school engagement?”, correlations’ were first calculated for academic motivation and school engagement all of their domains. The correlation matrix are shown in Table 9

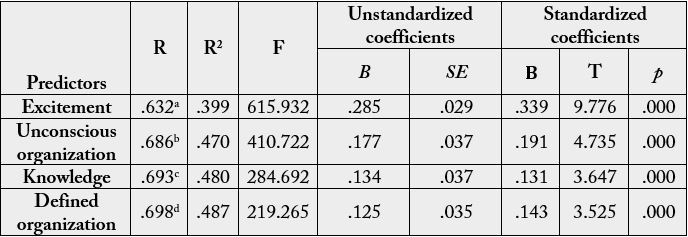

Table 9 shows positive correlations at the level of α ≤ .05 between academic motivation and school engagement and their dimensions. So, multiple regression analysis was used to test for the predictability of academic motivation dimensions (knowledge excitement, achievement, external organization, unconscious organization, defined organization) on school engagement as shown in Table 10.

Results of table 10 shows that four academic motivation dimensions predicted significantly scores of school eengagement. The Excitement domain explained 39.9% of the variance of school engagement, while, the other three dimensions (unconscious organization, knowledge and defined organization) explained 8.8% of the variance school engagement (7.1%, 1.0%, 0.7% in order). All four dimensions of academic motivation explained (69.8%) of the variance of school engagement.

In addition, the ability of academic motivation total scores in predicting school engagement was calculated. Results showed that academic motivation total scores predicted (47.5%) of the variance of school engagement (R2 = .475, F (1, 927) = 838.527, p < .001).

Discussion

The results showed that the overall scores of academic motivation and school engagement were higher

for males than females and higher for higher school grades in both scales. In addition, the results showed

that four academic motivation dimensions predicted significantly scores of school engagement where

the excitement domain explained (39.9%) of the variance of school engagement while, the other three

dimensions (unconscious organization, knowledge and defined organization) explained (7.1%, 1.0%, 0.7%)

in order. Results also showed that academic motivation total scores predicted (47.5%) of the variance of

school engagement.

As for the results of the first question, which indicated the superiority of male students on academic motivation, this can be due to the notion that males in general have more self-esteem and self-efficacy than females, which increases their academic motivation toward learning.

Social norms often play an important role in explaining low academic motivation in females since the population in the present study came from a low socio-economic status. So, males tend to do significantly better than females but the general means remain low for both males and females [31]. The high level of academic motivation among higher levels of school grades is a result of maturation and rabid cognitive development among higher levels grades [32].

As for the results of the second question, which indicated the superiority of male students on the level of school engagement, researchers attributed this Signiant differences to the differences in socialization processes in a low social-economic urban area in Jordan. Urban families often favor males over females in school needs and possibly follow-up on their male sons at the school as an attempt to improve their success and possibly completing high schools in order to move their sons to the labor market. Females in low socioeconomic areas looks at their daughters’ accomplishment as a secondary need, which may reflect on their engagement in school activities [33]. The high level of school Engagement among higher levels of school grades can be explained in terms that higher level grades are in middle stage of adolescence. This stage requires students to have more driplines to avoid many problems our rural schools face such school violence, delinquency and low academic achievements.

The results of the third question, which indicated that there is a predictive ability of academic motivation in students’ school engagement is a logical and realistic findings since the two variables are significantly and positively correlated. When students develop more academic motivation, they tend to like their school more, values their teachers, and eventually try to maintain these outcomes by participating in school activities.

It is worth noticing that the best domain in academic motivation that predicted school engagement was the excitement domain, which predicted alone (39.9%) of the variation of school engagement. Excitement means that students’ who have positive feelings and emotions toward the school and the learning processes tend to pay more attention to the school environment. Students’ who are highly driven and feel the need to re-act are the best combination to engage in their schools [5,34]. This finding about the importance of academic motivation in school engagement receives many support from previous studies Maulana, Helms- Lorenz and Grift, (2016) [17,28,34].

Based on the findings of the study, the researchers recommend the followings:

1. Exploring other social and cognitive factors that can predict school engagement among all levels of

schools.

2. Hold a training & workshops for teachers in the basic stage to improve their students’ ability to develop

academic motivation in order to improve school engagement of students in the school.

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!