Biography

Interests

Milagros Suyu, C.

Cagayan State University, Andrews Campus, Tuguegarao City, Cagayan, Philippines

*Correspondence to: Dr. Milagros Suyu, C., Cagayan State University, Andrews Campus, Tuguegarao City, Cagayan, Philippines.

Copyright © 2019 Dr. Milagros Suyu, C. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

The Philippines is one of the world’s emerging diabetes hotspots. According to the International Diabetes Federation, the Philippines ranked in the top 15 in the world for diabetes prevalence. Philippines is home to more than 4 million people diagnosed with the disease - and a worryingly large unknown number who are unaware they have diabetes. How a diabetic takes care of his health everyday determines the quality of his existence. The major purpose of the study was to determine the self-management needs of the diabetics to come up with a sound development program that could be implemented by the extension experts in the university, the health-care providers and civic-society organizations. The respondents included all the diabetic patients registered in the Diabetes clinic of a government hospital. Data were gathered through interview schedule. Other pertinent data were taken from the patients’ individual medical chart. Descriptive and inferential statistics were utilized to interpret the data. Results showed that the areas of concern needed by the diabetics are meal planning, self-monitoring of blood sugar, sick day management, exercise, knowledge of high and low blood sugar and foot care. The diabetics expressed their interest to become “managers” in their own care.

Introduction

The Philippines is one of the world’s emerging diabetes hotspots. According to the International Diabetes

Federation, the Philippines ranked in the top 15 in the world for diabetes prevalence. Philippines is home

to more than 4 million people diagnosed with the disease - and a worryingly large unknown number who

are unaware they have diabetes. A 2015 meta-analysis, done by Dr Gerry Tan of Cebu Doctors University

Hospital, noted that rapid urbanization in the Philippines is one of the factors that propelled the upward trend

of the disease [1], there are several clinical settings where diabetes screening, education and management can

be organized and delivered. For example, at the level of the barangay health station (BHS), the health worker

should have the capability to deliver diabetes self-management education, do blood pressure and weight/

BMI monitoring but it will be at the level of the rural health units (RHU)/City or Provincial Health Office

where diabetes clubs will be encouraged to be set up. At all levels of health care, education and training will

be done so that health care workers will have the competencies needed for health education, screening and

management. The strategy will be patient-empowerment; the team should be centered on the person with

diabetes focusing on self-management.

Self-management education (SME) is defined as a systematic intervention that involves active patient participation in self-monitoring (physiological processes) and/or decision making (managing). It recognizes that patient-provider collaboration and the enablement of problem-solving skills are crucial to the individual’s ability for sustained self-care [2,3].

Self-management is a concept emerging from Albert Bandura’s social cognitive theory which is based on the principles of self-regulation, self-control, and self-efficacy [4]. Self-regulation refers to an individual’s ability to monitor or manage oneself. Self-regulation constitutes three components: (i) Self-observation: Monitoring ones’ behavior, (ii) self-evaluation: Making judgments about ones’ behavior in comparison with their own standards and their environmental conditions, and (iii) self-reaction: The emotional responses associated with the behavior. Self-control is the process of acquiring skills to gain personal control over one’s thoughts and actions to achieve the target behavior [3]. Finally, self-efficacy refers to the extent to which an individual is capable of performing a particular task or behavior. Self-efficacy takes into account individuals’ attitudes, perceptions, and emotions in relation to the behavior [4].

Within the domain of diabetes, self-management involves (i) attending regular checkups, and (ii) adherence to a physician-prescribed, tailored medication, and lifestyle.

Diabetes self-management education (DSME) is a critical element of care for all people with diabetes and those at risk for developing the disease. It is necessary in order to prevent or delay the complications of diabetes [5-7] and has elements related to lifestyle changes that are also essential for individuals with prediabetes as part of efforts to prevent the disease [8]. A 2015 meta-analysis, done by Dr Gerry Tan of Cebu Doctors University Hospital, noted that rapid urbanization in the Philippines is one of the factors that propelled the upward trend of the disease [9].

The primary objective of the study was to determine the self-management needs of the diabetics registered in a Philippine government hospital to come up with a sound development program and an individualized self-management kit for the patients.

Materials and Methods

The study made use of descriptive survey method of research. The respondents of the study consisted of 102

non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) patients of a government hospital. Data were gathered

through a written interview schedule. Interviews were started with an informed consent obtained verbally

from each of the respondents. The interview schedule was designed on the basis of the study objectives.

Experts in the field of diabetology helped the researcher refine the questionnaire. Needed data that were not

supplied by the respondents were taken from the patients’ chart at the Diabetes Clinic.

Data collected from the questionnaire were tabulated. Each questionnaire was number coded to safeguard

the confidentiality of the respondents. The study utilized the descriptive and inferential statistics.

For food items frequently consumed, mean scores were computed using a Likert type scale 1-To interpret data on food consumption, the following arbitrary scale was used:

Food most frequently consumed (.>4 times per week) were given a score of 4; Food more frequently consumed (.2-3 times per week) were given a score of 3; Food moderately consumed (.>1-2 times per month) were given a score of 2, while food least frequently consumed were given a score of 1.

Results and Discussion

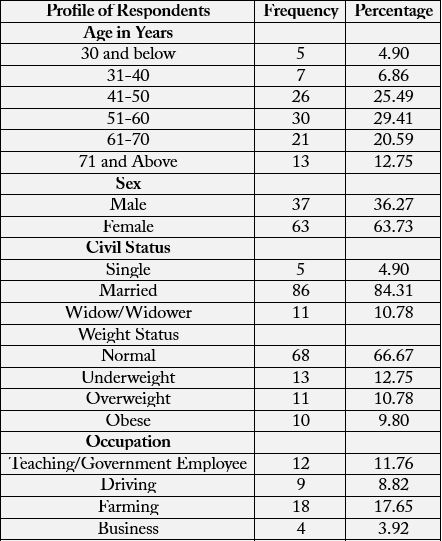

Table 1 presents the profile of the noninsulin- dependent diabetes mellitus patients in Cagayan. The

noninsulin-dependent diabetic patients are as young as 23 years old and as old as 76 years old. The table

shows that the majority of them are between 41-70 years old. The average age of the patients is 54.73. There

are 26 (29.41%) respondents aged 51-60 years. This was followed by those aged 41-50 years (25.49%). Of

the 102 respondents only 5 (4.90%) and 7 (6.86%) belong to 30 years and below, and 31-40 years age groups

respectively. These findings indicate that there is no specific age when diabetes could occur. However, data

collected indicate that diabetes is highest among the 41-70 years old patients.

In the Philippines, according to the Food and Nutrition Research Institute-Department of Science and Technology 8th National Nutrition Survey, diabetes prevalence based on fasting blood sugar has risen from 3.4 percent in 2003 to 5.4 percent in 2013. The greatest numbers of Filipinos with diabetes are 50 to 69 years of age and wealthy, and live in urban areas.

According to the interview, the respondents knew they had diabetes only after they submitted themselves for random blood sugar (RBS) testing. Hence, they were encouraged by their physicians to be admitted for further evaluation.

Of the 102 respondents, 3 or 36.27% are male while 65 or 63.73% are female. This finding implies that there

are more female respondents who seemed susceptible to diabetes mellitus than male respondents.

The phenomenon of more female respondents could be explained by women’s more concern for health than do males, that men are more or less skeptical of medical care and that women take more preventive action particularly those associated with medical interventions. This could explain why there are more female than male respondents in the study. This finding of the study suggests that measures should be taken by health care providers to encourage male clients to improve their health promotion and prevention behavior.

Data on civil status reveal that majority of the respondents are married and most of these are women.

Nutritional status, as indicated by weight, is one factor that predisposes one to diabetes mellitus.

Data on weight status reveal that a great majority of the respondents’ weight is normal based on the weight for height table. Some 21 respondents are obese and/or overweight. The data run counter to the belief that if one is overweight or obese, he/she is most likely to have diabetes. Those with normal weight could contract diabetes, although obese and overweight are at greater risk of type 2 diabetes.

On occupation, majority of the respondents are housekeepers and some don’t even have jobs, and are

therefore belonging to low income bracket. From this data, it can be concluded that diabetes mellitus is

not only a disease of the people with higher socio- economic status but affects as well those in the lower

economic status.

Only 6% of the respondents had elementary level education. According to this study, prevalence rates

are lower in people with higher education regardless of sex. It must be noted that education influences

income and income influences the type of clinic people go to. This study has for its subjects the patients

of a Philippine government hospital. Based on observation and experiences many people who patronize

government hospitals are the lower income clients.

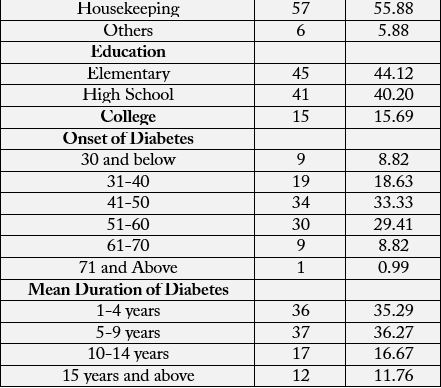

Results showed that the majority of the respondents have been diabetic when they were at the ages from

41-50 years old. Thirty respondents experienced the disease when they were at the ages between 51-60 years

old, while 19 have acquired the disease when they were from 31-40 years of age. Nine of the respondents

were diabetic before they were 30 years and below and after they were 61-70 years old. Only one has been

found to be diabetic when he was 76 years old.

The data showed that majority had the disease for less than 4 years to 9 years now. From the data presented,

one can surmise that there is an increase in the number of diabetic patients. There are more patients who just

contracted the disease than those who had it for longer years.

When asked if they were willing to go for diet counseling, 83 respondents said yes. Other responses included

“it depends” (5), if time permits (14).

The way one chooses, prepares and consumes food affect body chemistry.

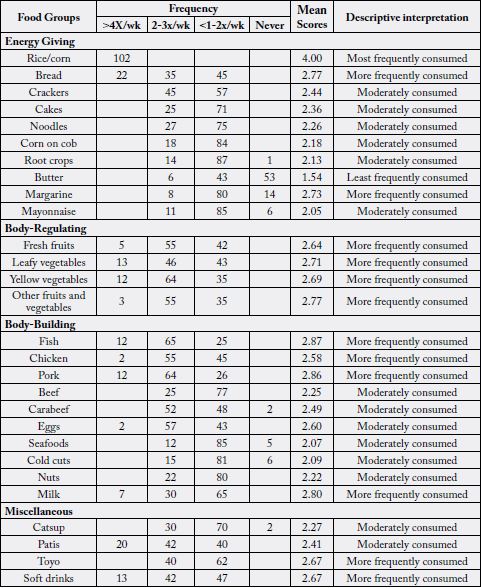

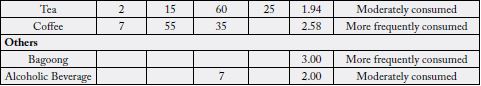

Table 2 presents the food commonly consumed by respondents prior to diagnosis. Data on food commonly

consumed by respondents according to basic food groups showed that most frequently consumed energygiving

food was rice. More frequently consumed are bread and margarine. All of the rest of the foods belonging

to the Energy-Giving Food are least frequently consumed. All body-regulating foods that include fresh

fruits, leafy vegetables, yellow vegetables and other fruits and vegetables are more frequently consumed. For

the body-building foods, more frequently consumed include fish, chicken, pork, eggs and milk. Moderately

consumed foods include beef, carabeef, seafoods, cold cuts, and milk. Miscellaneous items that were more

frequently consumed are toyo, soft drinks, coffee, bagoong. All the rest are moderately consumed.

When asked about foods they would like very much, the respondents gave the following ranked in this order: vegetable dishes, pork dishes, fish and seafood, sweets and desserts, and poultry. Family, lifestyle, personal characteristics, income, nutrition information and the disease itself are the most influential factors affecting food habits and food consumption pattern among NIDDM patients. Attitudes and beliefs about food develop from birth, from being born into a particular culture, society and family and these, the most influential is the family. The example given by parents is the basic model that the children follow in developing their own attitudes and food habits. In turn, the parents’ attitudes and habits are affected by several factors including ethnicity, traditions, food availability, convenience, economic status, positive experience with specific foods, beliefs and nutritional consideration. It is important therefore to know and to take family background into consideration when attempting to change or modify a person’s dietary practices. The respondents in this study had established long dietary habits that are hard to lick. Those who give diet counseling to people with DM must consider this.

As shown in Table 2, food liked very much by the respondents include vegetable dishes, pork dishes, fish and

seafoods, sweets and desserts, and poultry.

Diet plans become useless when they are not followed. Barriers experienced by the respondents in following

their therapeutic regimen Too many food restrictions, limited quantity of food intake, not being able to

enjoy food, Other reasons given why they find difficulty adhering to their diet are having to say no to food

offers, barrier to usual life, eating at specified time, and no appetite.

Based on the interview, only 14 (13.73%) of the respondents follow their diet regularly. Reasons given by those who don’t follow are: lack of self-control, feel bored with the diet, and lack of knowledge about the diet. It is said that the initial reaction after diagnosis of the disease is a feeling of depression, dependence and withdrawal which may be resolved within a year.

Some respondents in the study cited the changes in dietary habits they had to make. These findings pose a challenge to nurses, doctors and Nutritionist-dietitians to reevaluate their nutrition education approaches to make diet adherence more appealing instead of creating negative acceptance and unfavorable attitude towards diet. In the past, dietary advice for people with diabetes was too restricted and emphasized the don’ts and foods to avoid.

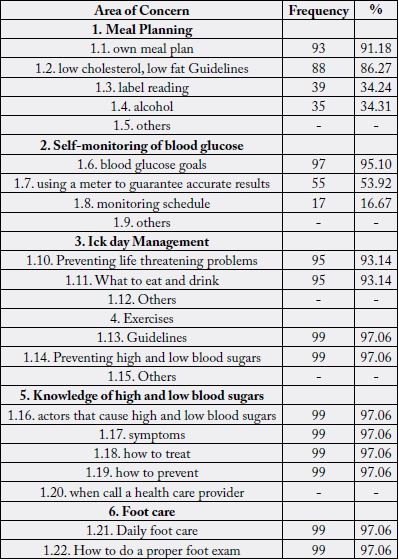

The 102 diabetic patients were given a checklist of diabetic management skills and knowledge they want to

acquire to achieve better glucose control. Table 3 presents these concerns.

Ninety-three (55.69%) like to know how to prepare their own meal plans, 88 (52.7%) want to know some

low cholesterol, low-fat guidelines, 39 (23.35%) needed to be given the importance of label reading,, while

35 (20.96%) need to know about alcohol in relation to their disease. This is signified mostly by the male

respondents.

In this area, ninety-seven (57.4%) wanted to be given some knowledge on how to achieve normal blood

glucose, 55 (32.54%) need to know how to use a glucometer to guarantee accurate results, 17 (10.06%) need

to know monitoring schedule.

Ninety-five (50%) wanted to know how to prevent life-threatening problems, and also 95 (50%) wanted to

know what to eat and drink on days they are ill.

Diabetes is a chronic disease that requires a person with diabetes to make a multitude of daily selfmanagement decisions and to perform complex care activities. Diabetes self-management education and support (DSME/S) provides the foundation to help people with diabetes to navigate these decisions and activities and has been shown to improve health outcomes [10].

Ninety nine (97.06%) wanted to know some exercise guidelines as how long, how hard, how often and when

the exercise shall be done.

Ninety nine of the respondents wanted to know the factors that cause high blood and low blood sugars the

symptoms, treatment, prevention and when to go to a doctor when they have low or high blood sugar level.

Ninety nine (97.06%) of the respondents wanted to know how to take care of their feet and to do proper

foot examination.

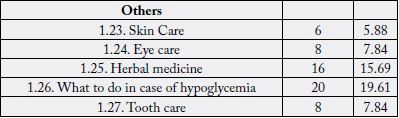

Other areas of concern mentioned by the respondents include skin care (6), eye care (8), herbal medicine

(16), what to do in case of hypoglycemia (20) and tooth care (8).

There are seven essential self-care behaviors in people with diabetes which predict good outcomes namely healthy eating, being physically active, monitoring of blood sugar, compliant with medications, good problemsolving skills, healthy coping skills and risk-reduction behaviors. All these seven behaviors have been found to be positively correlated with good glycemic control, reduction of complications and improvement in quality of life. Individuals with diabetes have been shown to make a dramatic impact on the development of their disease by participating in their own care.

Knowledge on the disease process, risk factors, prevention, signs and symptoms, treatment, self-monitoring procedure, sick day management, exercise and other diabetes information are the areas most of the diabetics want to learn. To address these concerns, a development plan was made. As mentioned by one of the diabetologists in Cagayan, Dr. Magnolia Reyes, information dissemination is the preliminary step in the prevention of the disease. She said that if there is a need to give them alarming figures, one has too, because as her experiences, some would not mind their disease unless they see someone very ill.

It was said that a well-informed and involved diabetic patient is more able to handle his or her own disease.

Helping people with diabetes to learn and apply knowledge, skills, and behavioral, problem-solving, and

coping strategies requires a delicate balance of many factors. There is an interplay between the individual and

the context in which he or she lives, such as clinical status, culture, values, family, and social and community

environment. The behaviors involved in Diabetes Self-Management Education (DSME) are dynamic and

multidimensional. In a patient-centered approach, collaboration and effective communication are considered

the route to patient engagement. This approach includes eliciting emotions, perceptions, and knowledge

through active and reflective listening; asking open-ended questions; exploring the desire to learn or change;

and supporting self-efficacy. Through this approach, patients are better able to explore options, choose their

own course of action, and feel empowered to make informed self-management decisions.

The enormous impact of diabetes mellitus on each patient is understandable, the reason why this disease is considered as matter of major concern. Education is an investment for both patient and health professionals, as well as the key to promote and improve diabetics’ quality of life.

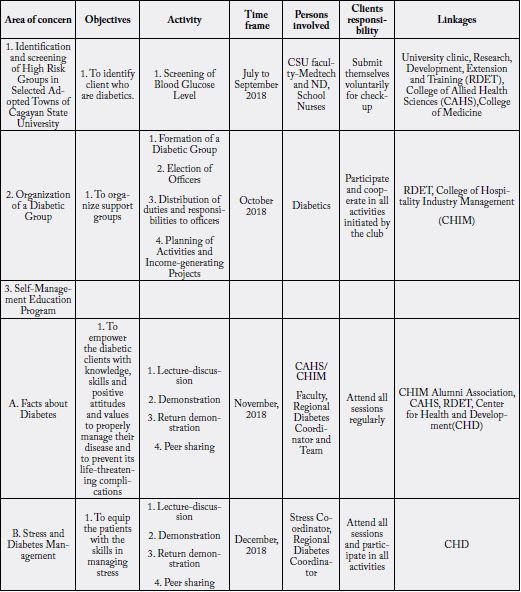

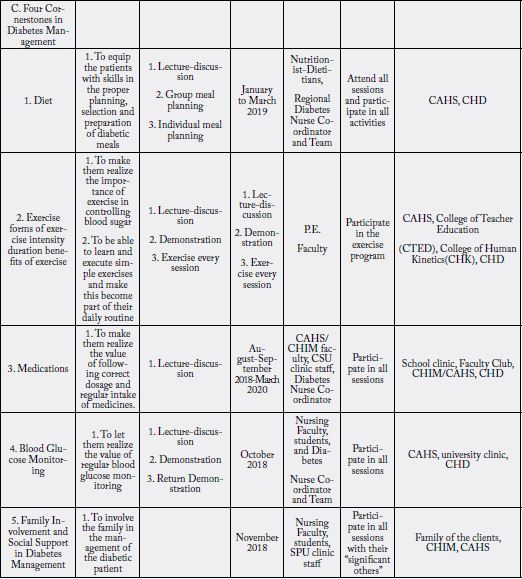

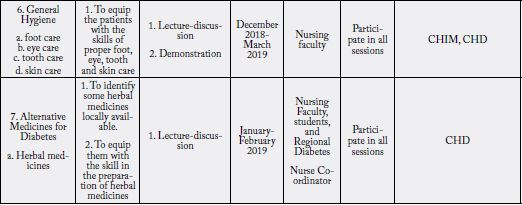

After determining the characteristics and needs of NIDDM patients, a development plan was proposed. Table 4 presents the development plan for NIDDM.

Proposed Development Plan for NIDDM

Effective, efficient and preventive health care can only be carried out by an involved and informed patient.

A Cagayano empowered to prevent diabetes and its life-threatening complications by themselves and by

their families.

To maximize community resources and open opportunities to establish diabetes awareness, conduct massive

information dissemination campaign and medical and guidance support, and other allied services in the

community.

1. To reduce the health, economic, physiological, social and psychological impact among the community

people by:

a. Making at least 30% of the Cagayanos aware of what diabetes is by year 2019 through 2020 and thereafter,

b. Reducing the rate of increase of prevalence of diabetes to 5% per year starting 2019.

2. To meet the needs of noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients through instructional support and guidance service designed to enable patients with diabetes to function at a maximum level of wellness.

Conclusions

Type 2 diabetes strikes anyone young or old, rich or poor, married or single, educated or not, normal weight

or obese. Basically, the diets consumed by the patients are healthy. This is seen in their inclusion of variety

of foods in their daily diet.

Majority of the patients resist changing their long standing dietary habits despite advantages they experience when sticking to the prescribed diet. Diet is one of the cornerstones to Type 2 diabetes treatment but the respondents stick to the easiest to take and follow-medication.

The respondents want to make themselves “managers” in their own care.

Recommendations

(a) Health practitioners like the doctors, nurses, nutritionist-dietitians as a group should exert efforts to

make their services accessible to NIDDM whose quality of life depends on a long-term dietary intervention.

(b) Barriers to dietary adherence must be part of the patients’ agenda for action

(c) Individualization and liberalization need to be emphasized in designing a meal plan for individuals with diabetes and for those with other chronic diseases.

(d) Patient empowerment is very crucial. The health care team cannot control diabetes without the cooperation of the patient and to be able to participate fully on his own care, the patient must be well informed and well motivated. Diabetes camps can address some aspects of diabetes education management.

(e) For the Hospital Diabetes Clinic to:

1. Provide ongoing regular self-management education among the diabetic patients with emphasis on the

topics of major concern;

2. Provide teaching-learning materials which are printed in bigger and bolder letters;

3. Provide opportunities for the diabetic clients to ask questions or clarify areas of concern during sessions

to help promote long-term adherence to therapeutic regimens particularly diet and exercise, which are key

to Type 2 diabetes control.

4. For other researcher to replicate this study in their diabetes center exploring other variables that may

affect knowledge, adherence to therapeutic regimen and metabolic control.

5. Provide more satellite or community-based diabetes centers to correct irregularity in their check-up.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to acknowledge the Chief of Hospital, personnel, particularly the personnel of the Diabetes

Clinic and the Dietary Department in the Philippine government hospital where the study subjects were taken. Their support to this scientific endeavor is highly appreciated. I wish also to acknowledge the

endocrinologists, the diabetes coordinators of the hospital and all those who were consulted to refine the data

gathering tool. To the respondents who gave their utmost support during the data-gathering phase,thank

you so much for your cooperation.

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!