Biography

Interests

Afodia Kassum, L.1*, Amin Igwegbe, O.1*, Florence Maina, J.2, Haziel Bala, K.1, Mohammad Makeri3, Mercy Kwari, I.1 & Amina Maijalo, I.1

1Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Engineering, University of Maiduguri, Maiduguri, Borno

State, Nigeria

2Department of Food Science and Technology, Federal Polytechnic Mubi, Adamawa State, Nigeria

3Food Technology and Home Economics Department, National Agricultural Extension & Research Liaison Services,

Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, Kaduna State, Nigeria

*Correspondence to: Dr. Afodia Kassum, L. & Amin Igwegbe, O., Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Engineering, University of Maiduguri, Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria.

Copyright © 2019 Dr. Afodia Kassum, L., Amin Igwegbe, O., et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Kunun zaki, a Nigerian local drink, was prepared using two cereal grains namely maize and millet. The objective was to determine which of the two grains is most suitable for the preparation of the drink. The products were subjected to chemical, microbial, organoleptic and rheological evaluations using the standard methods of analyses. Results obtained indicate that the kunun zaki prepared from maize and millet grains had percent moisture, protein, ash and carbohydrate contents of 78.86±1.32, 7.23±1.21, 2.02±0.49 and 8.92±0.34; and 80.66±1.41, 8.96±0.92, 2.48±1.00, and 4.88±0.13, respectively. The organoleptic qualities of the maize kunun zaki were rated highest especially in colour and the overall acceptability, while the millet kunun zaki scored highest in flavour only. No significant difference (p≥0.05) was recorded between the tastes of the two products. The microbial qualities of the products were observed to be within the limits prescribed by Regulatory Agencies and the products could be stored for up to four weeks under refrigeration temperatures. Also, the result of the rheological study showed that the products exhibited a Newtonian fluid flow as the power law index recorded was between 0.87 and 1.39. It was concluded that a highly nutritious and safe kunun zaki could be prepared from maize and millet grains which are in abundance in Nigeria.

Introduction

Cereals and legumes are important part of dietaries and contribute substantially to nutrient intake of human

beings. They are significant sources of energy, protein, dietary fiber, vitamins, minerals, and phyto-chemicals.

Primary processing of cereals and legumes is an essential component of their preparation before use. For

some grains, dehusking is an essential step, whereas for others, it could be milling the grain into flour. Grains

are subjected to certain processing treatments to impart special characteristics and improve organoleptic

properties such as expanded cereals. All these treatments result in alteration of their nutritional quality which

could either be reduction in nutrients, phytochemicals and antinutrients or an improvement in digestibility

or availability of nutrients. It is important to understand these changes occurring in grain nutritional quality

on account of pre-processing treatments to select appropriate techniques to obtain maximum nutritional

and health benefits.

Kunun zaki is a fermented, non-alcoholic beverage usually produced from cereal grains especially millet and is widely consumed in most part of Northern Nigeria especially during the dry and hot season [1]. kunun zaki is a term in Hausa language meaning sweetened beverage. The drink is popular especially in most parts of Northern Nigeria as a substitute to soft drinks, partly because it is relatively cheap and nutritious when compared to carbonated drinks that are more or less empty calories [2]. Cereal grains such as millet, maize and sorghum can be used to prepare kunun zaki alone or in combinations (Adeyemi and Umar,1995) [3,4]. In addition, other minor spice ingredients including ginger, clove, pepper and sweetening agents such as sweet potato paste, malted rice, or malted sorghum may also be added during the manufacturing process [5]. According to Agarry et al. (2010) [6] kunun zaki that is made from malted millet, rice, wheat and their composites with the addition of starter culture had better flavour, aroma, appearance, and overall acceptability over that made from other cereals. Several millet based products are also available in a variety of forms and conveniences in Nigeria. Beverages such as the alcoholic (burukutu, pito) and the non-alcoholic (Dambu, masvusvu) are very popular in most African countries [7-9].

Although the production of kunun zaki in Nigeria is still on the cradle and in a small scale, it is consumed by about 73% of the population in Northern Nigeria on daily basis and by 26% occasionally, especially during the dry and hot seasons [3,10]. Among the more than 13 types of cereal-based kunubeverages, kunuzaki is the most preferred and widely consumed beverage [3]. Millet is gluten-free, therefore an excellentoption forthe people suffering from celiac diseasesoften irritated by the gluten content of wheat andother more common cereal grains [11]. Kunun zaki is also a potential probiotic product produced by lacticacid spontaneous fermentation [12].

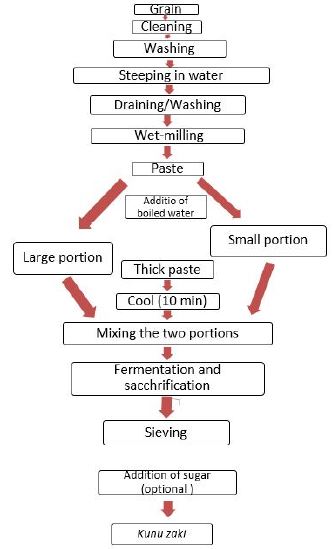

In the production of kunun zaki, the grains are usually steeped in water for 12-14 hours and then wet milled along with spice ingredients depending on type of grain employed and the desired flavour [3]. The slurry is then sieved and the filtrates left to stand overnight whereas the residue is discarded or fed to livestock.

Thereafter, the supernatant is removed and discarded leaving the sediment; the latter is the kunun zaki stock which can be used as it is or, may be wrapped in cheese cloth and allowed to drain out more water. However, because of the unsanitary processing environment, processing and post-processing storages usually employed by the locals, the microbiological quality of most kunun zaki has been adjudged to be very poor leading to a product with short shelf life of between two to three days [4]. And, despite the widespread consumption of kunun zaki in most parts of the Northern region, no particular cereal grain has been established as the most suitable grains for its production even as the possibility of processing the drinkon a commercial scale is yet to be investigated [6]. In addition, the products are observed being sold in the market and by hawkers in transparent polyethylene sachets and recycled plastic and glass containers that may result to foodborne hazards.The present study was therefore designed to compare the suitability of two abundantly available cereal grains (maize and millet) in the production of kunun zaki by assessment ofthe sensory, rheological properties of the products and their microbialstability. These investigations could assist in selecting the best grains for making kunun zaki as well asin recommending the best sanitary package for the product.

Methods and Methodology

The raw materials used in this study were maize, millet, spices (ginger) and sweetening agents (sweet

potatoes) and cane sugar, and they were purchased directly from Maiduguri Monday market in Borno State.

Analytical grade reagents were purchased from Chemical Suppliers within the city whereas the sample

preparation (cleaning, steeping and milling), kunun zaki processing, chemical analysis, orgnaleptic and

rheological studies were carried out in Food Science and Technology Laboratories, University of Maiduguri.

Two kg each of the cereal grains, maize and millet, were thoroughly cleaned and then steeped separately in

4 liters of distilled water for 24 hours at ambient temperatures. At the end of the steeping period, the grains

were drained and again thoroughly washed with distilled water, drained, and then milled separately using

an attrition mill (locally fabricated). The sweet potatoes were also cleaned, peeled, washed and grounded to

paste. Two liters of hot distilled water were added to each of the resultant flour to make slurry in separate

clean containers and with continuous stirring to avoid formation of lumps; and the slurry was allowed to cool

for ten minutes. Four hundred mg of the sweet potato paste was added to each ofthe grain slurries and then

allowed to ferment for eight hours at ambient temperatures. The slurry was filtered using a cheese cloth and

then sweetened with the cane sugar (Fig. 1),and the products were packaged in sterilepolyflorotetraethylene

plastic containers and sachets under strictly sanitary conditions.

The principal raw materials and the processed kunun zaki were chemically analyzed for the following

parameters: moisture, protein, fat and ash (or mineral matters). The moisture, protein, fat and ash contents

were determined in accordance with the procedures outlined in AOAC, 2005, Nielson, 2010, and Igwegbe

et al., 2019 [14-16]. Protein was determined through the quantification of the nitrogen content by the

standard Micro-Kjeldahl method [15,16] and multiplying the total nitrogen obtained by a conversion factor

of 6.25 to arrive at the protein content. Fat content was determined by the Soxhlet extraction method using

petroleum ether [14,16]. The ash content was determined following the procedures described by Igwegbe

et al. (2013 and 2019) [15,17].Whereas the moisture determination was carried out by step-up oven

drying of five grams of the samples at 115ºC until a constant weight was obtained [16]. Finally, the percent

carbohydrate content was obtained by subtracting the sum of protein, fat, ash and moisture from 100 [18].

Sensory evaluation of the prepared kunun zaki drinks was carried out to determine the taste, colour, flavour

and overall acceptability of the products. A total of twenty one taste panelists consisting of students and staff

of the University of Maiduguri who regularly consume the locally prepared kunun zaki and therefore are

familiar with the desirable characteristics of good quality kunun zaki were engaged in the sensory evaluation.

The coded samples were randomly presented to each panelist who was asked to assess and score each product

for preference on a 9-point hedonic scale with 9 representing extremely liked and 1 representing extremely

disliked in line with the descriptions of Igewgbe et al. (2015) [18]. Thepanelists were further asked to

indicate any observed difference in appearanceand to score the extent of variation among the products. The

viscosity and fluid flow properties of the kunun zaki drinks were also determined using the method described

by Sopade and Kassum (1992) [13].

Viable bacteria and mould counts were conducted on the prepared kunun zaki drinks using potato dextrose

agar (PDA) for the mould count and nutrient agar (NA) for the total aerobic plate-count,All glassware,

including Petri-dishes, test tubes, pipettes, flasks and bottles used in the microbial analysis were sterilized

in a hot oven at 170 ± 5ºC for at least two hours, while the media and distilled water were sterilized by

autoclaving at 121ºC for 15min and at 15 psi [19]. Each medium was prepared according to the manufacturer

‘sinstructions. Serial dilutions were madeby shaking one ml of kunun zaki sample in 9ml of distilled water.

Plating was carried out in triplicate and pour plate method was used to make the viable count [20,21]. In this

method, one ml of the inoculums was mixed thoroughly in molten plate count agar held in a hot water bath

at 47±2ºC. The agar was allowed to set; the plates were inverted and then incubated at 32ºC for 24-48 hours

for bacterial counts and at 25ºC for 5-7 days mould counts. For each dilution, the viable colonies, which

appeared colourless, in the three plates were counted and the mean was calculated. The microbial analyses

were carried out on the refrigerated samples of kunun zaki at weekly intervals for a period of 4 weeks.

The data generated from this study were analyzed using Analysis of Variance [22] and the tests for significant

differences between the means were determined using the Duncan‘s Multiple Range Test [23] at 5% level of

significance. The results were expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD).

Results and Discussions

Globally, cereal grains have been the principal component of human diet for thousands of years and have

played a major role in shaping human civilization. Around the world, rice, wheat, and maize, and to a lesser

extent, sorghum and millet are important staples critical to daily survival of billions of people. It is estimated

that more than 50% of the world daily caloric intake is derived directly from cereal grain consumption.

Most of the grain used for human food is milled to remove the bran (pericarp) and germ, primarily to meet

sensory expectations of consumers. The milling process strips the grains of important nutrients beneficial to health, including dietary fiber, phenolics, vitamins and minerals. Thus, even though ample evidence exists

on the health benefits of whole grain consumption, challenges remain to developing food products that

contain significant quantities of whole grain components and at the same time meet consumer expectations.

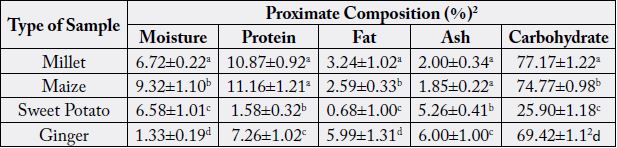

Nevertheless, the results of the proximate analysis conducted on both raw materials and the prepared kunun

zaki recorded in this study are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

The proximate composition of the raw materials showed that they are good enough to make good qaulty kunun zaki drinks as the values obtained in this study were quite in agreement with those obtained by Kent (1983) and Ihekoronye and Ngoddy (1985) [24,25] in similar studies. The results showed significant differences (p≤0.05) between the percent protein: 10.87±0.92 and 11.16±1.21, and ash: 2.00±0.34 and 2.59±0.33 contents of raw millet and maize samples, respectively; whereas the raw materials varied significantly (p≤0.05) in their percent contents of moisture, fat and carbohydrate (Table 1).

1Values are means of three determinations ± Standard Deviations;

2In every column, means bearing different superscripts are significantly different (p≤0.05).

The percent protein, fat, ash and carbohydrate obtained in this study are higher than those reported in similar investigations by Nkama and Badau (1996) [26] and Oyeleke and Abdulrashed (1977), while the values for moisture were lower than that recorded by Sopade and Kassum (1992) [13]. The variations were however expected, and are considered to be as results of varietal differences of the grains and the other raw materials (sweet potato and ginger) used and the processing methods as has rightly been observed by many researchers elsewhere, including Slavin et al. (2000),Graham et al. (2001), Bressani et al. (2004), Burt et al. (2010),Gannon and Tanumihardjo (2014), Ai and Jane(2016) and Oghbaei et al. (2016) [27-33].

Different processing methods result in changes to the nutritional profile of cereal grain products, which can greatly affect particularly the micronutrient intake of populations dependent on these crops for a large proportion of their caloric needs. Studies on the effects of different processing methods on nutrient contents in cereal grains, from field to plate, indicate that, generally, the fresher and less processed the cereals are, the more nutrients they will retain. Highly milled cereals will have lesser moisture, protein, lipid, and ash contents in comparison to those milled to a lesser degree.

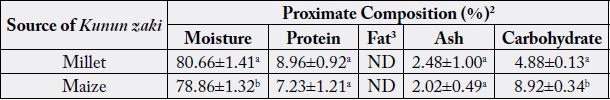

On the other hand, highly significant differences(p≤0.05) were observed in the percent moisture, ash and carbohydrate contents of the kunun zaki prepared from the two cereal grains, but no significant difference (p≥0.05) was recorded between their percent protein contents, while fat was not determined in the product, due to fact that the major fat-bearing components of the cereal grains were removed by the milling process (Table 2).

1Values are means of three determinations ± Standard Deviations;

2In every column, means bearing different superscripts are significantly different (p≤0.05).3ND

= Not Determined.

The higher moisture content as well as the increased concentration of the other nutrients could invariably be the reason for the thirst quenching property of the kunun zaki beverage when consumed and its more demand and consumption particularly during the hot dry seasons, as the beverage helps in replenishing moisture lost from the body, which is very common during the season.

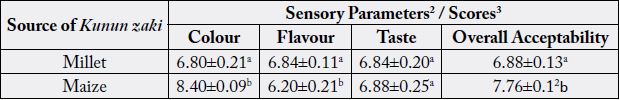

Usually, the organoleptic, as well as the nutritional properties are the most important motivators for liking

and purchasing of any processed food item. The objectives of any sensory assessment [18], may therefore be

for one or more of the following reasons: (i) to determine the presence of typically desirable characteristics;

(ii) to determine the presence and magnitude of undesirable characteristics; (iii) to describe the flavour

and/or aroma profile in the product; (iv) to determine whether one sample differs from another; and (v) to

determine whether one sample is preferred over another. Moreover, Table 3 shows the results of the panelists’

rating of the sensory attributes of the kunun zaki prepared in this study.

1Values are means of Scoring from twenty-one Panelists ± Standard Deviations;

2In every column, means bearing different superscripts are significantly different (p≤0.05).

3Scoring was based on a 9-Point hedonic scale, with 9 representing extremely liked and 1

representing extremely disliked.

The scores indicate that the kunun zaki prepared from millet has significantly better (p≤0.05) flavour (6.84±0.11) whencompared with that made from maize (6.20±0.21). However, the maize kunun zaki was rated significantly higher (p≤0.05) than that of millet in terms of the colour: 8.40±0.09 and 6.80±0.21, respectively, and the overall acceptability: 7.76±0.12 and 6.88±0.13, respectively; whereas, no significant difference (p≥0.05) was observed between the taste of the two drinks (Table 3).

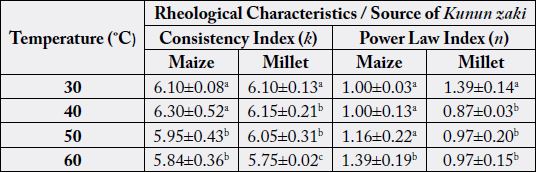

The data recorded from therheological assessment of the maize and millet kunun zaki drinks are presented in Table 4. The values obtained for Consistency Index (k) and the Power Law Index (n) were measured between the temperature range of 30 and 60ºC. The consistency index (k) ranged from 5.84±0.36 to 6.30±0.52 and 5.75±0.02 to 6.15±0.21 and the power law index (n) from 1.0±0.13 to 1.39±0.19 and 0.87±0.03 to 1.39±0.14, respectively. The power law index values for the two samples which were used to classify foods into Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids are either one or close to one and these are in agreement with the values recorded in this study (Table 4).

1Values are means of three determinations ± Standard Deviations;

2In every column, means bearing different superscripts are significantly different

(p≤0.05).

These values are also in consonance with the values reported by Sopade and Kassum (1992) [13] indicating that these drinks exhibited Newtonian fluid behaviour and is not temperature dependent as also indicated by Arslan et al. (2005) and Arslanoglu et al. (2005) [34,35]. Food rheology is the study of the rheological properties of food, that is, the consistency and flow of food under tightly specified conditions. The consistency or degree of fluidity of a food, and indeed other mechanical properties are important in understanding how long food can be stored, how stable it will remain, and in determining food texture. In addition, the acceptability of food products to the consumer is often determined by food texture, such as how spreadable and creamy a food product is. Food can be classified according to its rheological state, such as a solid, gel, liquid or emulsion, depending on their associated rheological behaviours, and its rheological properties can be measured [1].These properties have been reported to determine the design of food processing plants, as well asshelf-life and other important factor - including sensory properties that appeal to consumers [36]. Finally, the most importantfactor in food rheology is consumer perception of the product. This perception is affected by how the food looks on the plate and/or the package as well as how it feels in the mouth, or “mouthfeel”. The mouthfeel is in turn, influenced by how food moves or flows once it is in a person’s mouth and determines how desirable the food is seen to be.

In the food industries an increasing amount of attention is being given to prevention of contamination of

foods, from the raw materials to the finished products. The food processor is concerned with the “load” of

microorganisms on or in a food and considers both kinds and numbers of organisms present. The kinds

are important in that they may include spoilage organisms, those desirable in food fermentation, or even

pathogenic microorganisms.

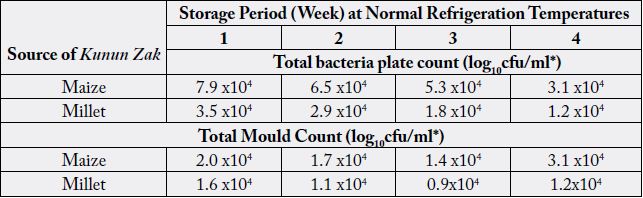

The numbers of microorganisms, on the other hand, are important because the more spoilage organisms there are, the more likely the food spoilage will be, the more difficult the preservation of food, and the more likely the presence of pathogens. In this study, the results of microbial assessment of the packaged kunun zaki stored under normal refrigeration temperature for a period of four (4) weeks are presented in Table 5.

1*Cfu/ml = colony forming unit per ml

1Values are means of Triplicate determinations

The results indicate low total bacterial and total mould counts from the kunun zaki drinks prepared from maize and millet. The microbial loads, more importantly, were observed to decrease with increasing storage period at normal refrigeration temperatures. This reduced microbial counts is thought to be as results of either the antimicrobial effects of the ginger used in the preparation, which is also in consonance with the observations of Farag et al. (1989), Badau (1992), and Sah et al. (2012) [37-39], or as result of the use of more hygienic processes during the preparation and subsequent packaging of the drinks, since the microbial load of any food may be the result of contamination, of growth of organisms, orboth. Also, it was observed that the prompt and sanitary packaging of the drinks after preparation provided additional protection against any chance contaminants. The quality of many kinds of foods is judged partly by the numbers of microorganisms present. The determination of microbial load is therefore important in estimating the food shelf life and also the suitability of the food for human consumption. Although both the total bacterial plate count and the total mould counts of the two drinks varied significantly (p≤0.05) throughout the storage periods (Table 5), the drinks are adjudged very safe for human consumption [40-42].

Conclusion

Primary processing of cereal grains is an essential component of their preparation before use. Most of

the processing treatments are designed to impart special characteristics and improve the nutritional and

organoleptic properties of the grains. The results of this study conclude that although both maize and millet

cereal grains yielded kunun zaki drinks that are similar in colour and the overall acceptability, kunun zaki

drink with the best flavour could be made from millet grains; and that prompt and sanitary packaging of the

product could lead to not only preservation of the nutritional quality of kunun zaki, but also to the extension

of the shelf life. Packages suitable for the packaging of Newtonian fluids will be most convenient in the

packaging of kunun zaki.

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!