Biography

Interests

Carlo Lazzari

Department of Psychiatry, International Centre for Healthcare and Medical Education (ICHME), Bristol, United Kingdom

*Correspondence to: Dr. Carlo Lazzari, Department of Psychiatry, International Centre for Healthcare and Medical Education (ICHME), Bristol, United Kingdom.

Copyright © 2019 Dr. Carlo Lazzari. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Interprofessional teams improve quality of care and patient safety. There is a growing interest in understanding how interprofessional education and practice (IPEP) functions and to endorse its philosophy in healthcare professionals. Furthermore, many hospitals and healthcare organizations have specific policies for the promotion of interprofessional education and practice in the health personnel. Therefore, understanding the dynamics of collaborative practice becomes pivotal for the improvement of research and applications in interprofessional teamwork. Social Network Analysis (SNA) is becoming a promising venue for understanding and representing dynamics and flaws in interprofessional practice. The current commentary explores the basics of IPEP and the application of SNA research.

Abbreviations

IPEP: Interprofessional Education and Practice

SNA: Social Network Analysis

Introduction

Interprofessional Education (IPE) occurs when students learn to collaborate by sharing responsibilities

and their know-how with colleagues. IPE is fast becoming a core training component in undergraduate

and graduate medical schools. In effect, the growing sub-specialization of medical and nursing schools and

the growth of specialized hospitals are gradually reducing the dialogue between healthcare professionals in

distinct specialties and between those who work in different wards and catchment areas. These events could

lead to an increased risk of fragmented care, reduced quality of care for patients, and a higher likelihood of

unattended needs and, in extreme cases, a more significant chance of medical errors. During recent years,

there has been a development in research instruments to assess and explore interprofessional education and

practice. One of the latest is Social Network Analysis (SNA) which allows triangulation of research methods

while capturing the dynamics of collaborative practice. The current commentary explores the central aspects

of interprofessional education and practice (IPEP) and the flaws in collaborative performances that can be

captured by SNA.

Definition of Interprofessional Education

IPE is defined as follows: ‘Interprofessional education involves students of two or more professions learning

together, especially about each other’s roles, by interacting with each other on a common educational agenda’

[1]. The World Health Organization describes IPE as follows: ‘Interprofessional education occurs when

students from two or more professions learn about, from and with each other to enable effective collaboration

and improve health outcomes’ [2]. The Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE)

provides another description: ‘Interprofessional education is occasions when members or students of two

or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care

and services’ [3].

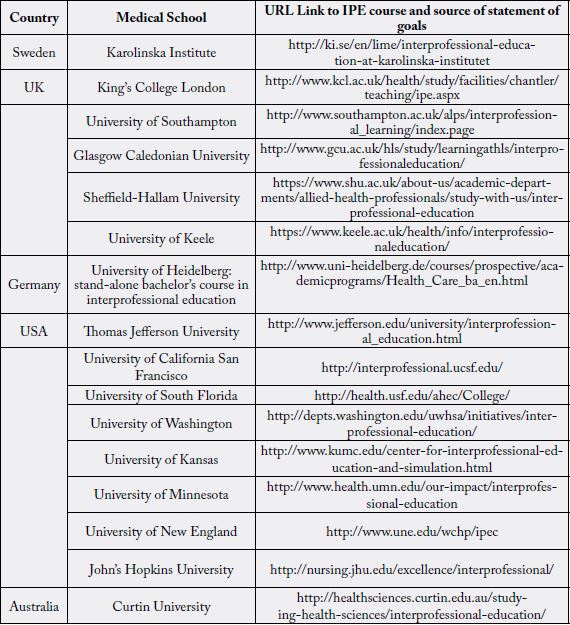

Curricula in Interprofessional Education in Medical Schools Around the World

As a stand-alone module or a short or long course, interprofessional education and practice (IPEP) have

been introduced in medical schools, nursing schools, and pharmacy and physiotherapy schools in several

universities around the world (Table 1). A research project involving sixteen American medical universities

indicated that the most popular forms of IPE instruction included team-based learning and simulations

[4]. In American teaching hospitals, the professions mostly involved in IPEP are nursing (89%), pharmacy

(59%), allied health (45%), physician assistants (39%) and social work (35%) [5]. The various formats for

IPE training include small-group classes (27%), large-group lectures (22%), simulation laboratories (10%)

and community organizations (10%) [5].

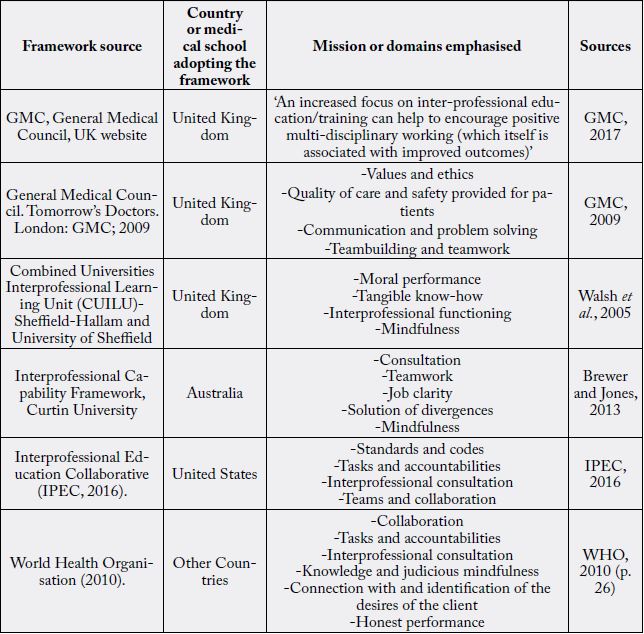

Competencies and Frameworks in Interprofessional Education

IPEP has become a major learning goal in medical schools and hospitals around the world. This current

commentary explores many of the IPEP frameworks that universities or organizations offering an IPEP

course have created to direct the training and assess the outcomes (Table 2). The interprofessional competency

frameworks adopted by several countries (Table 2) allow medical teachers to design IPEP courses and

reinforce the skills learners need in order to become operative members of interprofessional teams [6].

Different countries adopt some variations of the basic principles in IPE. In the United Kingdom, the General Medical Council [8,9] focuses on the need for multidisciplinary practice as a professional requirement for doctors and as a route leading to improved conditions of treatment and protection for patients. Other UK-based medical schools, like Sheffield-Hallam and the University of Sheffield, created the Combined Universities Interprofessional Learning Unit (CUILU) to guide interprofessional training. For instance, the CUILU emphasizes the importance of reflective practice and the ethics in teamwork for a successful IPE [10].

The interprofessional framework introduced by Curtin University in Australia highlights the need to improve communication, conflict resolution, and reflection to advance collaborative practice [11]. Furthermore, each member of the interprofessional team should be able to recognize how his or her expertise integrates with that of others [11]. The Interprofessional Educational Collaborative adopted in the United States emphasizes ‘interprofessional communication, team building, and teamwork’ as central in IPE emphasizing that communication and social skills are essential to working in an interprofessional team [12]. Lastly, the World Health Organization highlights the importance of recognizing the need of the patient and that learning with critical reflection is necessary for interprofessional practice [2].

Summary of Key Points from the Frameworks

IPE competences have been divided into six domains; each contains the major skills that students in IPE,

and health carers working in interprofessional teams, should master to succeed in cooperative practice [6].

These domains summarize what are suggested as being IPE frameworks and the practitioners’ needed skills

in mastering interprofessional practice [2,8-12]:

- working collaboratively with colleagues from other healthcare fields

- recognizing barriers to cooperation

-understanding functions and duties of each participant of the interprofessional team

-providing unified care to patients

-questioning stereotypes linked to roles

-communicating personal ideas to other members

-actively listening to other members

-proficiently communicating data about common patients

-using self-reflective practice to improve cooperative care

-using collaborative practice to enhance outcomes of care, client safety and decrease medical mistakes

-recognizing the individual biases towards others and acknowledging others’ opinions

-promoting an atmosphere of joint esteem and collective principles

Social Network Analysis in Interprofessional Teams

The interprofessional practice entails the dynamic interaction between different professionals, with individual

skills and behaviors, aiming to the shared goal of patient care and quality of life. Although there is extensive

freedom for each professional to decide the own course of accomplishment, each one is regulated by a

different professional body, and the level of personal autonomy complies with the legal and ethical demands

of the own profession. All the competencies of the framework are dynamically shared, which means that there

is a constant flow of giving and take about collaboration, roles, responsibilities, communication, learning,

interactions with patients and with agencies outside to hospitals or wards.

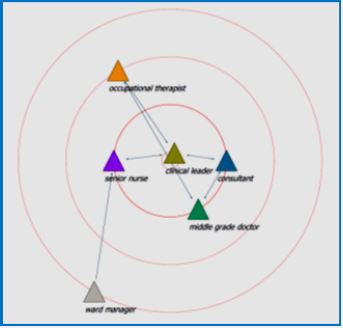

A complex network of interactions, communication, exchange of information and expertise occurs within interprofessional team members. Furthermore, these interactions are dynamic and very adaptable according to the needs of care and requirements of patients and members of the team. Within a team of interacting healthcare professionals, there is a constant exchange of information and advice about patient care. Furthermore, different professionals are more tied within themselves and interact more frequently compared to others who also belong to the multi-professional team. Hence, dyadic and more extended sub-groups and clusters characterize a network of relations between interacting professionals. Also, within these subgroups, there are those who more frequently provide information and advice and those, instead who require constant guidance and frequently seek information and guidance from others. Partly, personal knowledge and experience can explain the flow of information and advice but also personal factors like self-esteem, accountability, and leadership skills.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in using Social Network Analysis to capture interprofessional teams relations and in providing both figurative and mathematical models to describe the typologies of their interactions. In a social network, we usually refer to ‘relations’ between units while a ‘Social Network is defined as a set or sets of actors and the relation or relations defined on them’ [13]. As the social network could be inclusive of different typologies of relations, in interprofessional teams, it can occur that not all the configuration of ties are advantageous to team members and in patient safety and quality of care.

Researchers using SNA to study task-based groups can eventually help interprofessional teams recognize how to improve their approaches [14]. Also, a graphic representation of SNA offers some advantage over quantitative research [14] by visually evidencing hidden interactions within the actors of a network [15]. SNA is a collection of qualitative methods portraying interpersonal and social events inclusive of interactions, connections, group bonds and consultations that connect one unit of the network to other units while seeking statistical significance of the forms of these interactions [16]. The units of the social network are usually called ‘nodes’ and are presented by persons or groups and ‘ties’ that represent some form of mutual exchanges between the nodes that can have different arrangements [17]. Exchanges between units are usually represented by double-headed arrows representing information sharing, trading of assets, or cooperative ventures connecting subjects in the network [17]. There are numerous parameters indicating the typology of interactions between units. The author of the current commentary has found that the one which can mostly represent the exchanges types in the healthcare system is ‘degree centrality’ and the subcategory of ‘indegree centrality’ indicating the number of ties received by one actor from others - also indicating the ‘prestige’ of that unit - and ‘outdegree centrality’ the number of ties by one actor to others - also indicating the ‘expansiveness’ of that unit [18].

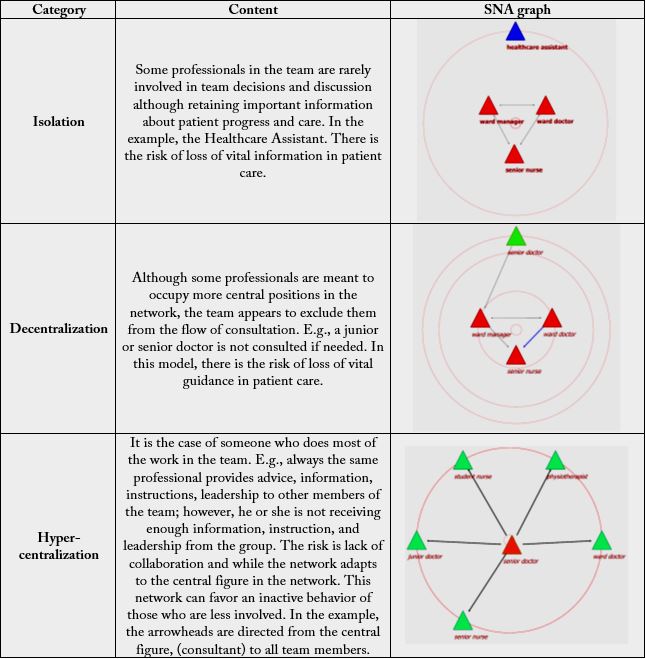

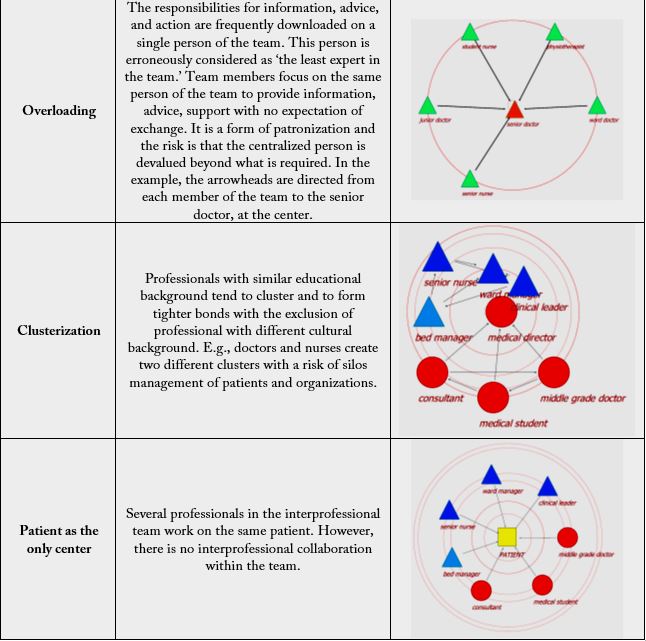

At the moment, several software programs are used to generate the math of social networks. The author of the current commentary has found the open source SocNetv 2.4 [19] program useful for this purpose. SNA starts from the assumption that all bonds between units are dependent on each other [20]. Therefore, the routine statistical methods that look for independent samples cannot be applied in SNA research. Hence, SNA can help identify areas of reinforcement within interprofessional teams. The major categories of flaws in interprofessional practice that the author of the current commentary has observed can be described as following (Table 3):

Conclusion

The current commentary has highlighted the importance of interprofessional education and practice in the

promotion of integrated care and the advancement of patient health and safety. Interprofessional curricula are now adopted by almost every healthcare organization which might decide to focus on specific components

of interprofessional practice. Nonetheless, also the most experienced interprofessional teams can show

interpersonal dynamics which can jeopardize collaborative care. There is an increasing interest in adopting

Social Network Analysis for research in interprofessional practice. SNA has the advantage to capture the

graphical dynamics of interpersonal practice while providing mathematical models to describe how people

in a team interact in integrated care. The current commentary has suggested that some of the flaws in

interprofessional practice that can be easily evidenced by using SNA models.

Acknowledgements

The author is thankful to the interprofessional teams that have been observed and that have provided the

vital insights for the completion of the current commentary.

Conflict of Interests

The author declares no conflict of interest. The author declares that he has no financial or personal

relationships that may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this article. Part of the content of

the current article was extracted from the author’s introduction in an unpublished master dissertation at the

University of Dundee.

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!