Biography

Interests

Brian Mayahle1*, Steve Parnell2, Rob Rolls3, Anthony Welch4, Jennieffer Barr5 & Fumiso Muyambo6

1Team Manager, Department of Healthcare Management, CQUniversity, Australia

2Director Operations and Innovations CQHHS, Australia

3Team Manager, Central Queensland Acute Care Team and AODS, Australia

4Associate Professor, Associate Professor Mental Health, Discipline Head, Mental Health, CQUniversity, Australia

5Associate Professor, Deputy Dean of Research, CQUniversity, Australia

6PhD student, Disaster Management Training and Education Centre for Africa (DiMTEC), Faculty of Natural

and Agricultural Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

*Correspondence to: Dr. Brian Mayahle, Team Manager, Department of Healthcare Management, CQUniversity, Australia.

Copyright © 2018 Dr. Brian Mayahle, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

To ensure consistent care for mental health consumers when admitted in rural and remote hospitals

and subsequently contribute to the management of regional acute mental health inpatient unit

beds.

The admission process in Central Queensland rural mental health services has been compromised

by diminishing resources and increased demand for the service. This has resulted in compromised

provision of consumer care, reduced consumer engagement, poor consumer outcomes and frustrated

staff.

Therefore, the impetus of this paper is to present the application of Lean practices to the rural hospital mental health admissions procedure, in order to create clear processes and care expectations, to enhance consumer outcomes and rural hospital staff confidence and role clarity when providing care to admitted mental health consumers. If mental health consumers can be admitted safely in rural hospitals, this would address the issue of increasing demand for regional acute mental health inpatient beds, as care would be provided in the consumers rural locality.

The study utilised a qualitative approach through an online ‘survey monkey’ questionnaire to develop

in-depth understanding of the perception and experiences of hospital and mental health staff.

The participants reported that the improved standardised work processes were clearer and simpler

to understand which resulted in more efficient service and therefore, increased consumer safety and

rural hospital staff confidence to admit and provide care.

Introduction

There has been an increase in demand for mental healthcare services throughout the rural hospital emergency departments (EDs) in Central Queensland. There is no single reason that explains the increased mental health presentations in EDs. However, the increase can be attributed to the associated drug use, increasing community awareness of mental health issues and an ageing population. The changing national economic conditions such as unemployment rates, resources sector downturn and wages stagnation are major contributing factors to development of mental illness in rural and remote communities. The impacts of natural disasters; for example, the floods and cyclones that recently hit the Central Queensland region such as cyclone Marcia in 2015 and cyclone Debbie in 2017 also affect mental health. It can also be partly explained by the fact that EDs in Central Queensland are generally the most flexible and easily accessible sector in a complex system of healthcare delivery in hospitals and the community. In addition, there are no financial constraints to consumers to access ED services, lack of bulk billing and after-hours General practitioners.

The need to pay attention to mental health services in regional, rural and remote areas has been raised by the Australian Government recently [1]. Research highlights that, whilst both policy attention and new funding were being directed towards Australian mental health services, there was still a significant number of people with a mental illness not seeking help or not receiving appropriate treatment because of insufficient services, in addition to fragmented and uncoordinated systems, especially in regional, rural and remote areas [2].

Several studies suggest that suicide rates, homicide, alcohol and tobacco consumption National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) 2016 [3], as well as untreated mental illness in rural and remote communities, could be higher than in metropolitan settings, but there is no broad consensus in Australian research to confirm this phenomenon [4]. However, social issues and behaviours that are sometimes indicative of mental illness, such as violence and self-harm, appear to occur at a higher rate in rural and remote areas [5-7], particularly among rural indigenous populations [2].

Waiting lists, lack of treatment options or the need to travel to access healthcare services may result in a considerable proportion of the population with mental health challenges not accessing support services, or not receiving treatment due to cost and time barriers, until their condition has deteriorated significantly [6]. Consequently, by the time consumers present to rural hospital emergency departments they will be requiring hospitalisation.

Mental health services have been criticised as lacking capacity and vision to ensure high quality care, particularly for people living in rural areas [8]. Regional mental health inpatient units’ beds are frequently fully occupied; hence, the need to admit some of the mental health consumers as outliers in rural hospital facilities. In spite of all this, there are no national or state-wide initiatives that have been developed and systematically implemented to comprehensively address or resolve issues of access, appropriateness of care and accountability in rural hospitals for mental health consumers (AIHW, 2005). The approach to provide care in rural hospitals for mental health consumers has been generally ad hoc, driven by the need for urgent political solutions to local crises. It is essential for rural and remote hospitals to have sufficient capacity to manage consumers according to standard protocols, where possible.

Sustainable solutions to meet the increasing demand for brief mental health admissions in rural and remote facilities, as well as increasing capacity, would require adequate analysis of the processes. Identification of clinical process steps from admission to discharge from the facility either to an inpatient acute mental health facility or back to the community was necessary, before any solutions can be implemented. If all stages of clinical service provision are clearly defined, then services can be labelled in a proactive manner; that is, aligned and configured around individual needs as well as leading to improved consumer outcomes. After clearly describing the care processes, a collaborative working approach between all stakeholders, including community mental health teams, will be required to seamlessly navigate the consumers through the system.

Lean thinking specifically has shown great potential for improving quality of care and processes in several departments of the general healthcare system [9-11]. Much success in the healthcare industry has been reported in emergency departments, pharmacy, radiology, pathology, transport, operating theatres, HR, IT or food services; to generate a continuous improvement culture through identification and elimination of waste within the processes [12]. Lean is described as a process management philosophy that examines organisational processes from a customer perspective with the goal of limiting the use of resources to those processes that create value for the end customer [11]. The impetus of this project was to develop clear processes on managing rural hospital mental health admission in cahoots with all key stakeholders using Lean principles to ensure consistent high-level care for the consumers and contribute to the regional mental health units’ bed management.

Research Methodology

The study utilised qualitative methodology. It implemented naturalistic inquiry using the method proposed

by Braun and Clarke (2006) [13]. The socio-technical aspects of Lean (humanistic factors) could be better

understood by having a good understanding of staff perceptions of internal quality and Lean implementation

in healthcare. The healthcare industry has various cultures, structures, professional bureaucracies and norms

which require qualitative methods to explore people’s perceptions and experiences Maxwell (2008) [14], Yin

(2008) [15], and Tharenou, Donohue, and Cooper (2007) [16].

The online ‘survey monkey’ questionnaires had open ended questions to allow participants to express their

pre- and post-Lean implementation knowledge, views, experiences and perceptions regarding the quality

improvement methodology. The post-Lean implementation questionnaire was addressed to staff who

participated and those who utilised the processes that were developed in the Kaizen workshops (group

activity which can last up to five days, in which a team identifies and implements a significant improvement

in a process) The questionnaires are attached as Appendices A and B respectively

This study used convenience sampling. A convenience sampling framework was appropriate as a specific

health region was targeted to consider the usefulness of this business approach.

The online survey monkey questionnaire was created and administrated by an independent administrator

with a locked password. The online questionnaire had a consent box and an additional information sheet

contained a statement that there were no consequences if they decided not to participate. Participation was

not mandatory but was highly recommended to improve the services.

This project required ethics approval as it involved human participants. Ethics approval was sought from the

appropriate institutional ethics committees, Central Queensland University (CQU) and Central Queensland

HHS Human Research Ethics.

The online questionnaire was anonymous; therefore, participation or non-participation in the study was

non-identifiable. The online questionnaire was locked with a password and administered by an independent

administrator.

A total of 26 responses were elicited from 40 participants, which translates to 65% response rate. The

participants comprised of rural mental health staff, the acute care team and the rural hospital staff. The

responses could not be categorised to the specific areas because of the need to maintain anonymity.

Nevertheless, the cohort of participants was a cross-section representation of the regional mental health and

hospital workforce staffing profile which includes psychiatrists, allied health, nurses and administration staff.

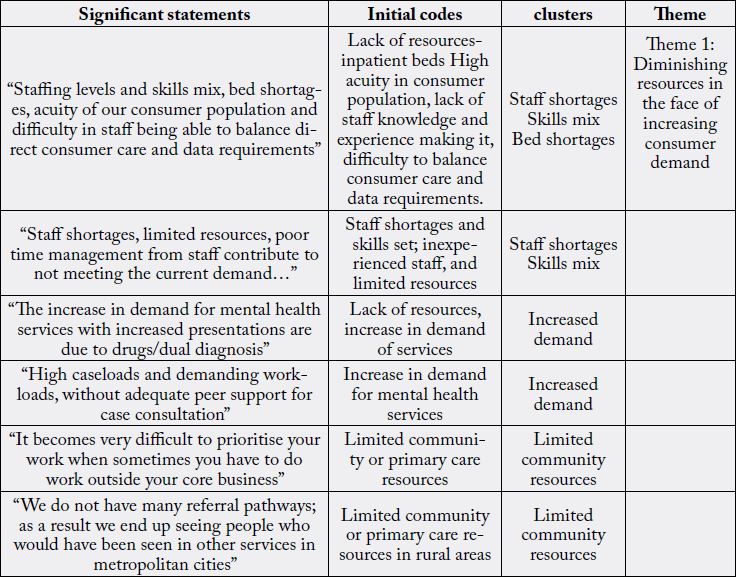

The responses to the open-ended questions used in the online questionnaire were analysed following the six phases of thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (2006) [13] who posit that it is a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data. This method was chosen because it organises and describes the data set in (rich) detail while providing in-depth interpretations of the data in meaningful ways Boyatzis (1998) [17]. Therefore, in line with the six phases by Braun and Clarke (2006) [13] we familiarised ourselves with the data by independently reading through the responses so as to come up with a well organised story. Secondly, we generated initial codes, which resulted in 6 identified codes. The third phase was to search for themes. 6 codes yielded 2 clusters which were reviewed to generate initial themes. In the fourth phase we reviewed the initial themes by cross-referencing them. All participants were identified and given equal weighting. The emergent themes were synthesised and the process was repeated until there was minimal overlap in the remaining categories. Fifthly we defined and named themes after there was minimal overlap and five themes emerged. Finally, a report was produced. The significant statements, initial codes, clusters and theme is presented in Appendix C

The theme that emerged from the analysis was diminishing resources in the face of increasing consumer

demand. The identified clusters that fall under this theme were; increased demand, staff shortages and skills

mix, as well as lack of external resources, for example, psychological services. The diminished resources

mentioned by participants were categorised into two:

1. The internal resources at secondary level care mental health services (Queensland Health Acute and crisis management teams)

2. Resources in primary care services sector in rural areas (NGOs, GPs and allied health services such as psychologists and social workers)

Some participants mentioned that the general increased referral activity caused by the recent coal mining

downturn in Queensland and Australia, had not been matched with capacity due to budget constraints,

as expressed in the following statement; “the increase in demand for mental health services and increased

presentations are due to drugs/dual diagnosis as well as the economic downturn”. As a result, the resources

could no longer meet demand. Another issue raised by the participants was ‘high demand of services’, which

leads to high caseloads for the clinicians. “There are now high caseloads and demanding workloads, without

adequate peer support for case consultation” noted another participant. In addition, staff shortages and skill

mix was also raised as a concern.

Another participant mentioned staff shortages as a major issue, in rural community mental health services,

which resulted in the services’ inability to meet demand by stating that; “Staff shortages, limited resources,

and poor time management from staff contribute to not meeting demand”…. Moreover, the participant

pointed out the aspect of lack of skills mix and role modelling in rural mental health services as a hindrance

to the provision of quality care. The following is the statement from one of the participants that highlighted

this view of lack of skills mix:

• “Staffing levels and skills mix, bed shortages, acuity of our consumer population and difficulty in staff being able to balance direct patient care and data requirements is an impediment to the provision of quality care”

It is noteworthy that it was also mentioned that there is need for general resources such as more acute inpatient beds in regional and rural centres. Closely linked to staff shortages is the lack of the correct skills mix and experienced staff who are good role models and could provide supervision and peer support. Another participant also highlighted the skills mix issue, but specifically mentioned the reduced accessibility of specialists (consultant psychiatrists), which resulted in mental health clinicians staff working outside their scope and consequently leading to huge workloads and inconsistent supervision for case managers. The participant stated that “…increase number of hours available for access with consultant psychiatrists in rural areas for case managers to be able to afford more contact time with clients…”

Other participants mentioned the unclear policies and procedures compounded with staff shortages and short-term contractual workers as resources that lacked in community mental health services, leading to unmanageable workload and inconsistency in service provision. One participant mentioned that “the current pathways would be more clear and easy to understand if they are depicted via flow charts”. In addition to simplified pathways and procedures, other participants highlighted the need for good orientation and adequate training when new staff joined the services. Effective orientation would subsequently provide new staff with a good understanding of the service processes, requirements and expectations so that staff can better manage their workload. One participant mentioned that “not having clear understanding of what is expected and lack of adequate training when joining the services with regards to expectations and the departments’ key performance indicators…”. Apart from the internal resources which were identified by participants as lacking, external resources in the rural communities were also highlighted as lacking.

Another cluster which posits the theme of diminishing resources in the face of rising demand was lack

of external resources in primary healthcare services. Lack of primary care or community resources was

highlighted as the reason why the rural community mental health services could not meet the demand,

resulting in clinicians ending up with busy workloads. One participant expressed this view by stating that

“We do not have many referral pathways as a result we end up seeing people who would have been seen in

other services in metropolitan cities. We do it all”. Another participant mentioned a similar view by stating

that “It becomes difficult to prioritise your work when, sometimes, you have to do work outside the core

business”.

A one-day kaizen workshop, to create the current state of admission, was conducted by key representatives

from rural community mental health staff, rural hospital emergency department, and regional acute care

team. The kaizen team discussed the number of mental health consumers admitted per year in rural mental

health hospitals, the number of admission at regional acute inpatient unit from rural and remotes areas in

Central Queensland, and service capability frameworks of rural hospitals. The data of admissions clearly

showed that there were more mental health admission episodes in rural hospitals (162) in a year as compared

to the regional acute inpatient unit (27) in a year, which necessitated the need for clear admissions process

to increase capacity and consistency in managing the rural hospital mental health admitted consumers. This

was then followed by discussions pertinent to gaps between state-wide recommended service provision and

current Central Queensland rural mental health service provision. Thereafter issues and constraints within

the current process were also discussed before embarking on developing the standard work flow charts and

rural mental health consumer admission care plan.

A significant issue raised in this workshop was lack of flow in the process as a whole. Flow is described as linking the, otherwise, disjointed links to ensure that consumers move in the process without any delays or waits. Issues on flow of information in the system were found to impact on treatment delays and clinicians’ involvement in provision of care. Any interruption results in disruptions to flow. The major obstacles to flow are the seven wastes as described by Taiichi Ohno (1988) [18]. Black and Miller (2008) [19] give seven types of flow in healthcare. However, the three major types of flow which were distinctive and relevant to this admission process are:

1. consumer flow;

2. information flow;

3. clinicians flow.

The kaizen team also acknowledged that Central Queensland region is sparsely populated, compounded by a tyranny of distance between geographical areas. The huge distances results in fragmented service provision, inaccessibility and inefficiencies. As a result, a more robust management of the mental health consumers in their localities was required. After reaching that consensus that real problems existed in the current process the team developed the current state process map of the admission process and then brainstormed to identify new ideas to improve flow. To improve flow and to create the desired future state, the team used the acronym FECRS which stands for:

F- Fix broken operations

E- Eliminate waste

C- Combine or collocate operations

R-rearrange operations

S-standardise and simplify operations

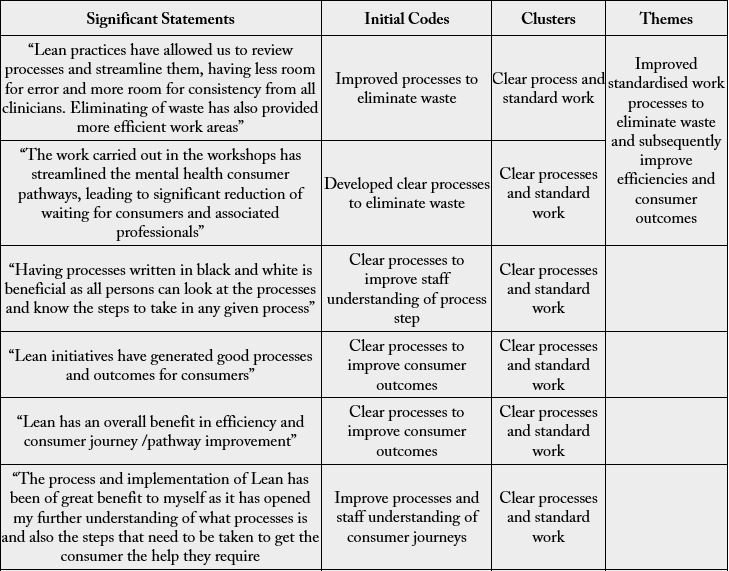

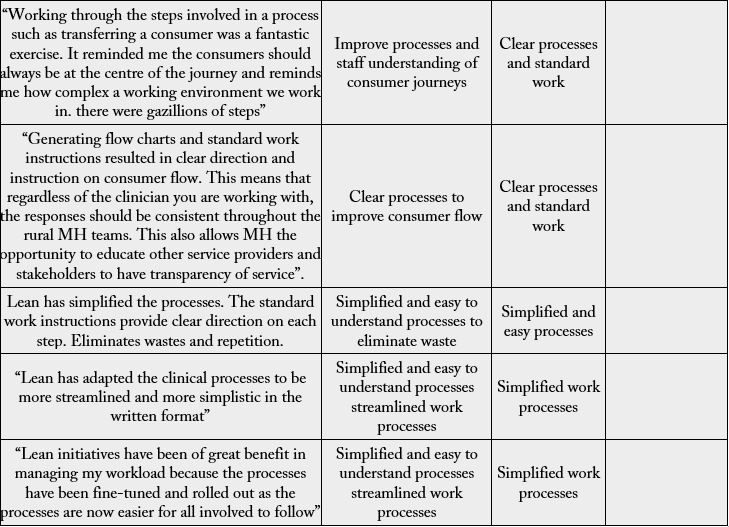

Once the future state processes were developed, the team then drafted the desired future state flowcharts and rural mental health admission care plan. The drafts were shared with other key stakeholders for further consultations.

Standard work is not a management tool to be imposed coercively on employees. Moreover, it is not

trying to enforce rigid standards that make the jobs routine and degrading, but it is the basis of employee

empowerment and innovation in the workplace. Therefore, the flow charts were emailed to various groups,

including the Clinical Director of mental health, rural hospitals, Director of Medical Services and Directors

of Nursing of rural hospitals who further consulted with their colleagues. The consultation occurred for a

month to allow all key stakeholders to provide all parties to have an input.

Taiichi Ohno (1988) [18] stated that standard work is the basis of having stabilised processes before any

continuous improvement can occur. It is impossible to improve any process until it is standardised (No

kaizen without standard work). If the process shifts without a set standard then it will be viewed as another

variation. As a result, the key results from the workshops were standard flow charts and the admission care

plan which would address the issues that had been raised in the workshop and also in the pre-Lean surveys.

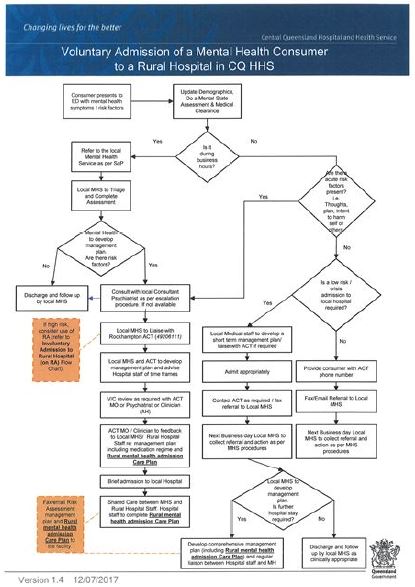

Figure 2 shows the voluntary admission of mental health consumers in rural hospitals. The flow chart clearly

shows the step by step tasks to be followed when a consumer is to be admitted in a rural hospital voluntarily.

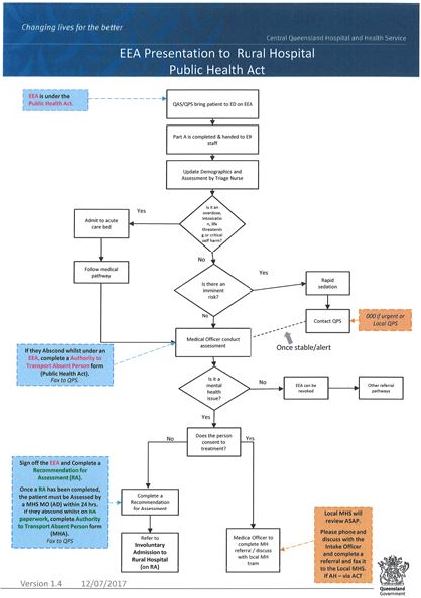

Figure 3 is a step by step flowchart which guides staff on how to respond to a consumer who presents to a rural hospital on an emergency examination order under the public act.

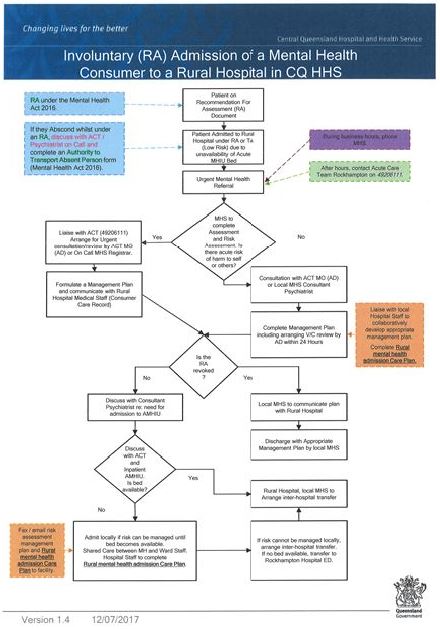

Figure 4 highlights simple step by step flow chart for managing an involuntary mental health consumer at a rural hospital when there is bed block at the regional acute mental health inpatient unit.

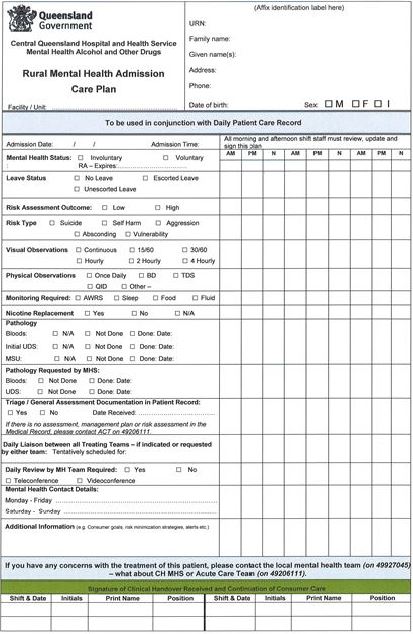

The team developed the rural mental health consumer admission care plan as shown in Figure 5. The rural mental health admission care plan would be completed by mental health teams and faxed to the rural facilities if the admission is carried out after hours. The community mental health teams would complete the care plan and share with the local hospital staff if the admission is done during working hours.

The team developed a communication plan and standard work training implementation spread sheet for

systematic dissemination of the newly created standard work instructions and flow charts. The communication

plan identified all the stakeholders, a timetable and how progress would be evaluated.

The standard work instructions were rolled out to community rural mental health staff, rural hospital staff, other remote and multipurpose facilities in the district and the acute care team staff. Clear roles and

• “The work carried out in the workshops has streamlined the mental health patient pathways, leading to significant reduction of waiting for patients and associated professionals”

• “Having processes written in black and white is beneficial as all persons can look at the processes and know the steps to take in any given process”

Two other participants correlated the standardised processes to improved consumer journeys and outcomes through the following listed statements:

• “Lean initiatives have generated good processes and outcomes for patients”

• “Lean has an overall benefit in efficiency and consumer journey /pathway improvement”

The standards processes were also identified to be easy to read and understand resulting in the improved clarity.

Lean initiatives created simplified and easy to understand processes that resulted in improved workload

management. One participant expressed the view by stating that “Lean has adapted the clinical processes to

be more streamlined and more simplistic in the written format”. The same sentiment was echoed by another

participant who stated that “Lean initiatives have been of great benefit in managing my workload because

the processes have been fine-tuned and rolled out as the processes are now easier for all involved to follow”.

Discussion

Pre-Lean implementation surveys highlighted negative responses towards resources that have been

diminishing in rural areas. Underpinning the pre-Lean theme were several other factors that included lack

of clear processes and expectations, staff shortages, high turnover of staff and geographical distances in rural

areas.

The issues on diminishing resources could not be adequately be addressed by streamlining the internal processes. To do so would require high level interventions at state-wide and government levels. For instance, both internal and external resources need to be included such as bed shortages, staff shortages and skills mix, psychological services as indicated in the pre-Lean surveys. The other services which are non-existent in rural and remote areas which would impact positively in meeting demand would include supported accommodation as well as step-up-and-down facilities in the communities. Lean implementation did not effectively address these issues as they were outside the scope or process boundaries.

The changes brought about by Lean made the services more efficient through reduction of waste and reduced variation, thus increasing capacity in already existing resources and consumer safety. This substantiates the fact that Lean focuses on gradually improving consumer experiences without necessarily adding or an injection of more funding to address the overall issue of resources and capacity.

Despite the limitation of Lean to directly address challenges of diminishing resources, the post-Lean implementation resulted in positive changes in identifying clear expectations. This resulted in consistency in managing consumer admissions in rural health facilities due to increased confidence and effective collaboration working through standardised work processes. This confirms the view of Graban (2012) [20] that Lean is an approach that can support employees and physicians, eliminating roadblocks and allowing them to focus on proving high standards or levels of quality care. While there are no statistical figures to back that up, Lean implementation ensured that consumers admitted in rural hospitals would be provided expected appropriate and safe care due to standardised work processes.

The team neither sought to increase nor had capacity to increase internal resources; however, they streamlined the admission process to increase the capacity to admit more consumers and provide great care in their localities. That is aligned to the overall 2030 strategic focus of Central Queensland health and hospital services of providing great care within consumer localities. Caring for consumers within their localities wherever possible reduced transfer costs and ensured that rural consumers could maintain their social supports when requiring brief admission periods. This substantiates Graban (2012) [20] who states that Lean is about eliminating waste in processes in order to provide better services using same or fewer resources rather than increasing funding for projects. However, implementation of Lean can inform service leaders on where resources need to be allocated.

Conclusion and Implications of Study

The study highlights that Lean philosophy can improve the admission process in regional, rural and remote

hospitals and contribute to the confidence of staff in managing mental health consumers. The key element

to achieving required goals is to involve the clinical staff in identifying the problems that will subsequently

result in relevant solutions to be developed and adhered to.

If staff from different departments develop processes jointly, that can address issues of staff animosity consequently increasing service utilisation and address issues of demand and capacity and future allocation of available resources. The process also provided or informed on how resources can be allocated since the exploration of improving the admission process partially addressed the bed management issues, but did not eradicate the bed occupancy issues at the regional centre. Instead it contributed to hospital staff being able to provide care with confidence and certainty for those consumers admitted at local hospitals.

Special acknowledgement to all the central Queensland rural mental health staff and rural hospitals staff, and the acute care team

Appendices

Please tick the box provided if you consent to participate in this research study

Writing in usual conversation style is acceptable to answer the questions in this document

Describe your understanding of Lean thinking philosophy?

Describe your understanding of mental health patients’ journey in central Queensland mental health services?

What do you consider as the “value adding” activities/steps in a patient’s journey within the mental health service?

What do you believe are some of the “non- value added” activities/steps in the current clinical process?

Describe the key performance indicators which relate to patients’ journey when they are referred to central Queensland mental health services?

What do you think are the challenges for meeting the current key performance indicators?

What are your suggestions in relation to IT, documentation, and data systems that will improve your workload and meeting key performance indicators?

Describe your understanding of the overall central Queensland mental health services strategy?

Describe the communication style between senior leadership and staff within the central Queensland mental health services?

What are your suggestions of how employees can be empowered and encouraged to be actively involved in improving the clinical processes and their work environment within central Queensland mental health services?

Based on your experience and knowledge, what are your suggestions about process improvements that are needed in Central Queensland mental health services to improve patient experiences?

Any other comments?

Please tick the box provided if you consent to participate in this research study

Writing in usual conversation style is acceptable to answer the questions in this document

1. What is your opinion of the CQWay/lean activities in which you have participated?

2. To what extent has your work with lean contributed to better workflow?

3. To what extent has the implementation of lean improved your work environment?

4. Which factors do you think obstructed the successful implementation of CQWay in rural mental health services?

5. Which aspects of Lean resulted in positive outcomes for, patients, you and the team?

6. Please describe how lean implementation in rural mental health services has helped you to perform your work?

7. Please describe how lean implementation has helped you to understand clinical processes

8. Please describe how lean implementation has helped you to understand Key performance indicators and overall CQMHAODS strategy

9. Any other comments

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!