Biography

Interests

Carlo Lazzari1*, Georgios Mousailidis2, Ahmed Shoka2 & Basavaraja Papanna2

1Department of Psychiatry, International Centre for Healthcare and Medical Education (ICHME), United

Kingdom

2Department of General Adult Psychiatry, Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust, United Kingdom

*Correspondence to: Dr. Carlo Lazzari, Department of Psychiatry, International Centre for Healthcare and Medical Education, United Kingdom.

Copyright © 2018 Dr. Carlo Lazzari, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Factitious Disorder (FD) represents a rare and challenging condition in primary and secondary care. The complexity of presentation of patients who are fabricating, or exaggerating illnesses requires an interprofessional approach to identify and treat FD successfully. The current article explores the critical routes for diagnosis and management of a disorder which can lead to unnecessary medical and surgical investigations with the risk of iatrogenic side effects or life-threatening outcomes if it remains misdiagnosed.

Abbreviations

FD: Factitious Disorder

BPD: Borderline Personality Disorder

DPD: Dissocial Personality Disorder

Introduction

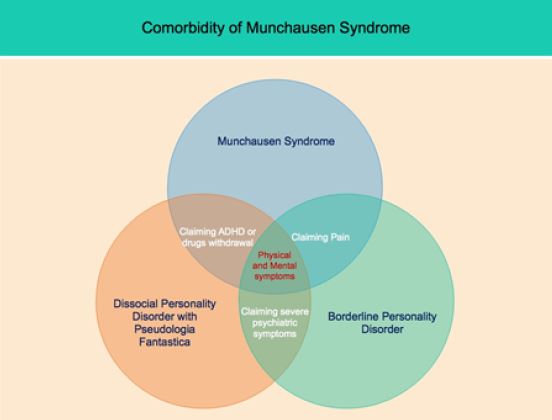

Factitious Disorder (FD), sometimes termed Munchausen Syndrome, is a well-known condition in liaison

psychiatry and medicine. The DSM-V [1] indicates that Factitious Disorder consists in the fabrication of

signs or symptoms, or the production of a wound or illness with the patient describing himself or herself as

unwell or wounded in the absence of severe mental illness. During recent years, the incidence of factitious

clinical cases has increased mostly linked to comorbidity of FD with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD),

Dissocial Personality Disorder (DPD) and depression, a condition that the authors of current commentary

named ‘Tripolar Syndrome’ (Figure 1) [2,3]. FD causes constant concern in staff and teams as patients

with FD might put their lives at serious risk by strategies of malingering. Self-inflicted wounds, illnesses,

or pathologies or exaggeration of symptoms and signs that cannot be readily cleared become a vicious

circle and a game with the health care system; in fact, the real nature of the presentation is often difficult to

interpret, clarify or modify. From here, the recurrent and chronic presentation of FD which is a challenge

to staff ’s endurance and clinical resources. There is some gender prevalence as the comorbidity of FD with

BPD is more frequent in female patients while comorbidity of FD with DPD is more frequent in male

patients [2,3]. The current commentary will explore the typical presentation of FD in primary and secondary

care and some strategies of management.

Materials and Methods

An ethnographic observational approach and the collection of narratives provided the methodology to

clarify the nature of beliefs and behaviors of patients suffering from FD and to suggest possible strategies of

management. Clinical observations by staff and the use of an ad-hoc scale (see Appendices) helped unmask

FD. The cases commented were mostly FD patients in an adult psychiatric ward offering liaison services

with the local general hospital.

Results

If unrecognized, the behaviors characterizing FD can become maladaptive and can lead to life-threatening

conditions. One common presentation is the problematic management of patients with FD; they tend to

undermine the therapeutic relationship with their primary carers while they could mount false allegations

towards doctors and nurses whenever they feel challenged or minimized in the true reasons of their behaviors.

Patients suffering from FD can find themselves voluntarily at risk of severe medical and surgical diseases.

They can self-harm or self-inflict medical and surgical pathologies while becoming highly dependent on

hospitals and healthcare services. They might harbor undisclosed plans to gain access to medical and surgical

procedures or to retrieve restricted medication. When in the hospital, their challenging behavior is often

conducive to intramuscular or intravenous therapy which yields some symptomatic benefit and is welcome

by patients with FD (e.g., mounting agitation to get intramuscular lorazepam).

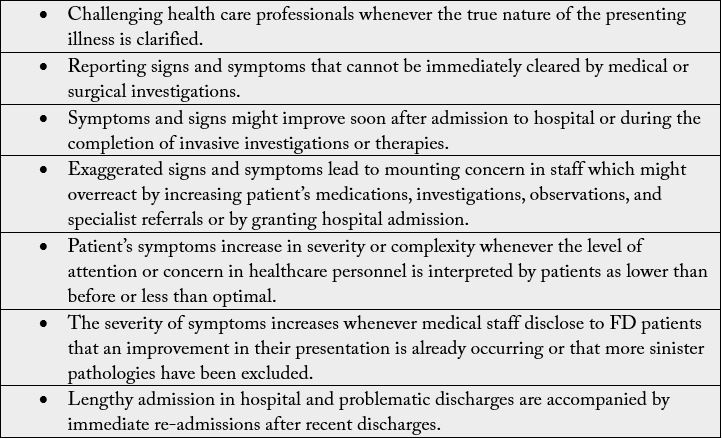

Patients with FD pretend, exaggerate or self-inflict physical and mental symptoms to access healthcare services and resources, psychotropic medication, sedative drugs, painkillers, and hospital admission. They might sabotage primary care services and family physicians by directly accessing a hospital via accident and emergency services. Besides, FD behavior can lead to undisclosed plans of manipulation of healthcare resources, staff and care plans. Therefore, FD usually results in lengthy admissions, constant conflicts between staff and patients with the syndrome and expensive, unnecessary medical and surgical treatments. Furthermore, patients with FD are hard to discharge from a hospital. Instead, they could actively resist any clearance from medical, surgical and psychiatric services. FD patients might tend to be readmitted shortly after discharge and become chronic bed blockers. A series of maladaptive behaviors tend to present in primary and secondary care. In the FD, maladaptive behaviors are a constellation of patient’s manners that challenge, stop, or threat any therapeutic plan is designed to improve their condition and quality of life (Table 1).

Hospital or community healthcare professionals might face the patient’s tendency to test carers and to make formal complaints against staff whenever his or her interpretation of the presenting illness is challenged, minimized or the true nature of the illness or signs are doubted. Besides, patients with FD frequently chose to report signs and symptoms that cannot be instrumentally or immediately falsified, like severe pain, untreatable dizziness, chronic epilepsy, severe depression or suicidality, and others. Consequently, clinical symptoms at admission to a hospital might appear dramatic or exaggerated while the patient’s presentation tends to normalize soon after entry in a hospital or whenever the desired clinical or surgical treatment is provided, or staff ’s awareness granted. Nonetheless, in a medical, surgical or psychiatric unit, patients’ exaggeration or malingering of psychical and mental symptoms can lead to mounting concern in unaware staff which automatically reacts by increasing current medication that is already on patient’s card, starting new clinical investigations, increasing the level of observation, or becoming more acquiescent with patients’ desires.

At the same time, the authors of the current commentary observed an increase in the severity of symptoms and signs whenever patients interpret the level of medical attention and medical or surgical investigations as being less than optimal. Another aspect which impacts on the healthcare management is that patients with FD tend to have lengthy admissions into a hospital with seemingly little improvement in their presentation. These patients might assert that there is no recovery in their pathology although proper medical and surgical treatment and investigations are already provided, and more sinister pathologies have been ruled out. Also, there are paradoxical relapses in symptoms and presentation whenever medical and surgical teams compliment with patients about their improvement. When the accurate diagnosis of FD is delayed, and due to the complexity of FD presentation, medical and surgical staff might start a chain of unnecessary investigations, therapies or specialist referrals. Unfortunately, when patients with FD are informed about negative (absence of pathology) outcomes of these investigations or assessments, they might react by disclosing new symptoms, increased pain, agitation and little progress ‘although’ current investigations result negative, and a targeted medication is already prescribed. Subsequently, FD maladaptive behavior can thus lead to novel factitious pathologies, new fabricated signs, and new self-inflicted wounds.

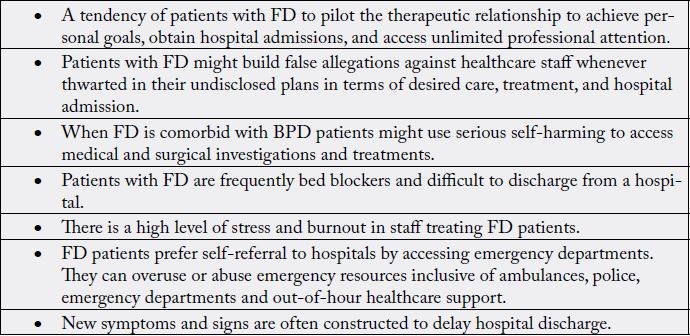

The therapeutic relationship with patients with FD is paramount for the successful completion of the

treatment and for favoring a successful discharge to the community (Table 2). However, patients with FD

might misuse the therapeutic relationship as a lever to access restricted diagnoses, medications, therapies

and hospital bed and to influence staff ’s emotions. Also, uninformed or unqualified staff might collude with

FD patients hence reinforcing their behavior. Besides, patients with FD might undermine the therapeutic

relationship with their primary carers or use false allegations whenever they perceive there is an obstacle or

a boundary to their undisclosed goals or when staff confronts patients about the fictitious version of their

illness.

When FD is comorbid with a borderline personality disorder or dissocial personality, patients might be at high risk of deliberate self-harm and parasuicide which might present to healthcare services as significant medical and surgical pathologies. Hence, a vicious circle ensues where self-inflicted wounds or medical conditions might become the passe-partout that patients with FD use to access hospital beds, exclusive healthcare services, medical and surgical wards or to obtain restricted psychotropic medications and painkillers. Some exaggerated behaviors in psychiatric wards acted by tripolar (FD-BPD) patients might occur to have medication administered intramuscularly or intravenously for rapid tranquillization. Patients use this factitious behavior as a form of masked self-harm. Typical presentations of FD in liaison psychiatry include a blend of deliberate self-harm, challenging behaviors, self-mutilation, overdoses of paracetamol, chronic and vague pain, and repeated access to medical or psychiatric hospitals via emergency departments.

Whatever is the hospital ward or specialty that patients with FD approach, staff treating them face distress and discouragement during a therapeutic relationship. FD syndrome frequently results in lengthy admissions, disputes between staff and patients and expensive and often unnecessary medical and surgical investigations and treatments. Staff might feel a loss of empathy due to the problematic interaction with patients with FD. Other times, unprofessional and collusive alliances between patients and some healthcare professionals ensue; in this case, patients are supported and accepted in their presentation, and hence their factitious behavior is reinforced. Most of the times, the hospital staff finds it difficult to discharge patients with FD back to their homes. FD patients might resist any clearance from medical and psychiatric services by reporting each time the occurrence of new symptoms or signs. Bed blocking can be a concern for hospital managers, and any constructive attempt to encourage patients with FD not to rely heavily on hospital admissions is met with unsuccessful results.

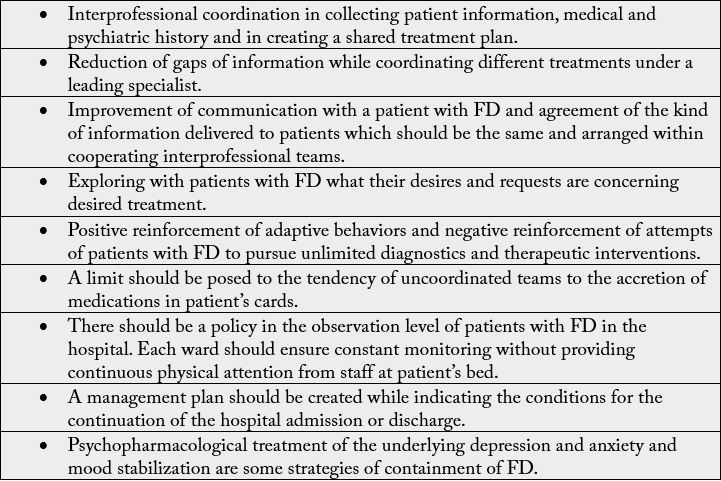

The management of FD requires a coordinated effort by part the part of all agencies and people working in

psychiatry and general medicine (Table 3). Therefore, an interprofessional team of healthcare professionals

should plan a coordinated action to deliver the same information and care to patients with FD and avoid

gaps in reporting and prevent divisions in their care. Any breaks in information regarding treatment,

decisions, and medication can be used by patients to split staff and generate misunderstanding within the

teams treating them. One leading specialist shall instead coordinate medical, surgical and psychiatric teams

in their clinical plans. Consequently, the significant hindrances to FD patient management are present in

the strategies of staff-patient communication. As discussed, the communication channels and interpersonal

dynamics between patients with FD syndrome and staff are halted or distressed at different levels both in

direct communication and meta-communication.

The feelings of people who attend to these patients are often characterized by manipulation and frustration; the demands and requests that patients with FD syndrome place on staff cannot be satisfied within mature adult interactions either in medical or psychiatric wards. If the intentions and needs of patients with FD syndrome are not immediately apparent to their carers, then the resulting misinterpretations and distress in the patient-carer dyad can reinforce the pathological accretion of more factitious symptoms. Consequently, staff should spend some time with patients with FD to clarify what are their desires and expectations regarding the possible therapies. Staff should also reinforce real boundaries to reduce the pursuit of patients with FD to receive an endless amount of attention and care from health carers by exclusively using fabricated signs and symptoms to access unlimited courtesy. As we have seen, FD syndrome creates concerns among healthcare professionals. Worries about these patients and the dramatization of symptoms often lead to immediate hospital admissions. Moreover, the use of multiple medications to address feigned symptoms risks creating iatrogenic illnesses.

Furthermore, the care and management of these patients, together with their lengthy admissions and expensive but redundant investigations, are a constant concern in healthcare policy. There is also a human cost in the management of FD syndrome. We find anxiety among staff who are unable to leave a patient with FD alone for even a single minute as these patients prefer to be under constant observation by multiple nurses in medical, surgical and psychiatric wards. If not satisfied in this quest, patients will quickly escalate to self-mutilating behaviors or by feigning more intense symptoms. Patients with FD syndrome might also refuse benign diagnoses, insisting that they do suffer from severe physical and mental illnesses. They hope to achieve lengthy admissions into psychiatric and medical wards, and they are notoriously hard to discharge back to the community due to a form of ‘hospital addiction.’

FD patients aim to an unlimited provision of staff ’s compassion, empathy, and attention considered as an entitlement. However, the pursuit of such attention is often achieved at the expense of emotional and objective crises and frustration in the nursing and medical staff treating them. Therefore, a contract with the patient might be necessary while indicating where the clinical investigations will terminate. Besides, the FD patient shall agree with staff the discharge plan when she or he has finally been declared medically and mentally fit. Without an integrated management plan, patients with FD syndrome can put the entire health organization at risk of burnout, physical and economical exhaustion or staff ’s abandonment of patient care. Also, the demanding and complex nature of the long-term treatment of FD syndrome requires exceptional resources not always available. Patients should thus be invited to explore their concerns not merely linked to their reported illness but also if and why they resist being discharged from the hospital or benign diagnoses. Psychopharmacological treatment of low mood and anxiety can also be considered although the best evidence is in favor of mood stabilizers while considering the potential and paradoxical effect of antidepressants which might instead increase FD symptoms or impulsive self-harming.

Conclusions

The current commentary has explored the presentation of FD in clinical practice. The assessment and treatment of patients with FD are complex while requiring an interprofessional collaboration. The authors of the article explored the typical presentation and the difficulties in establishing a therapeutic alliance with these patients. The awareness of the maladaptive behaviors in FD and a robust interprofessional plan can improve the presentation and reduce the risk of lengthy admissions to hospital with continuous medical assessments and unnecessary surgical operations. Further research is required to address the intrinsic needs of patients with FD and reduce the risk that healthcare organizations, as well as primary and secondary care, are jeopardized in their resources by the elaborate presentation of these cases. The current article has attempted to address some of the issues in diagnosis and treatment and in recognizing how frequently the presentation of FD syndrome overlaps with personality disorders. As the authors of the article have highlighted, only after the proper diagnosis of FD syndrome is made, it is also possible to improve the outcome in the treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to their teams that regularly provide support and professional attention to patients

with FD syndrome.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The authors declare that they have no financial or personal

relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Appendices

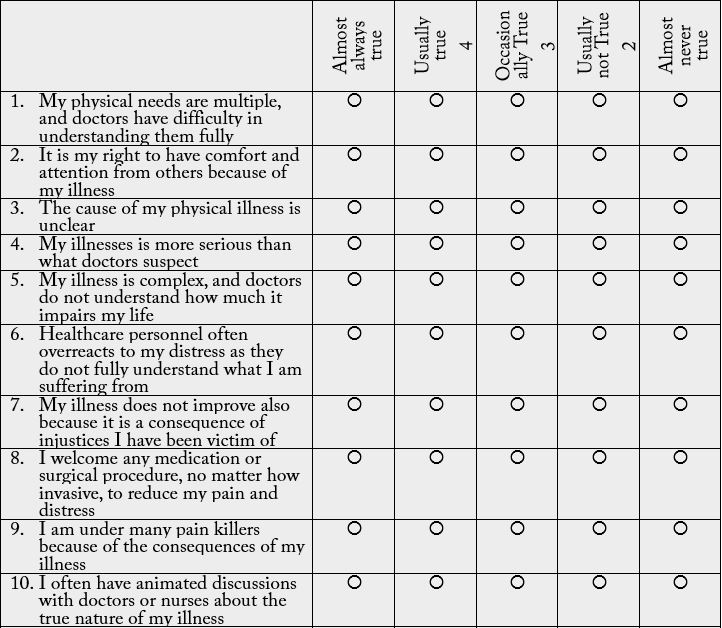

The authors of the current commentary have created an assessment scale for FD which can help in clarifying

patient’s distress and behavioral components of FD.

The Factitious Disorder Self-Assessment Scale (FDSAS)

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!