Biography

Interests

Content Creation and Ghostwriting Services, Medical Writer, Clinical Consultant Services, USA

*Correspondence to: Dr. Diana Rangaves, Content Creation and Ghostwriting Services, Medical Writer, Clinical Consultant Services, USA.

Copyright © 2023 Dr. Diana Rangaves. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Glossary of Terms

Sub-Acute Specialty Care

Introduction

Health care economics and patient outcomes are embedded in every facet of the health care model. Due to

their pharmaceutical knowledge and training, pharmacy technicians and pharmacists are poised to contribute

in the creation, development, and implementation of medication reconciliation. These opportunities are

consistent with Safe Practice Recommendations and Patient Point-of-Care.

http://www.macoalition.org/Initiatives/RecMeds/SafePractices.pdf

The Impact

Medication errors injure at least 1.5 million Americans annually, costing the nation more than $3.5 billion a

year [1]. Estimates suggest that up to 60 percent of patients have at least one discrepancy in their admission

medication history [2]. Experience from hundreds of organizations has shown that poor communication of

medical information at transition points of care is responsible for medication errors [3]. Poor communication

is known as the “common denominator” in medication errors.

Ineffective communication at significant patient exchange points (transition points of care): admission, transfers between care settings, and discharge, result in as many as 50% of all medication errors in the hospital and up to 20% of adverse drug events [3]. A uniform systems approach, designed to help organizations maintain their culture of safety, is critical.

Core ElementsPlan-Do-Study-Act and the Five Rights are integral in the clinical support of a medication reconciliation process. Understanding the rationale and evidence reinforcing the importance of the medication reconciliation process will support the health care team members in the creation, development, and implementation of a template.

The medication reconciliation process includes four steps:

1. Verify (collect a current medication list)

2. Clarify (make sure the medications and doses are appropriate)

3. Reconcile (compare new medications with the list and document changes in the orders)

4. Transmit (communicate the updated and verified list to the appropriate caregivers) [4].

This four-step process is to be conducted at each phase of transition in the patient point-of-care.

Goals

Medication reconciliation is a shared collaboration, bringing together responsible health care team members:

patient or patient’s representative, nurse and/or unit nurse manager, pharmacist and pharmacy technician,

physician, executive management and directors, and/or other allied health professionals.

The primary commitment is to the coordination of interdisciplinary efforts to develop, implement, maintain, and monitor the effectiveness of the medication reconciliation process. Throughout the continuum of care pharmacists and pharmacy technicians have a responsibility to educate patients and caregivers by obtaining a personal medication list. The goal of medication reconciliation is improvement in patient well-being through education, empowerment, and active involvement in the accurate transfer of medication information throughout transitions along the healthcare continuum [5].

Strategies

Medication reconciliation must be standardized across the continuum within an organization.

The data set must have common elements to facilitate the efficient transfer of information.

This systems approach is an effort to prevent medication errors, omissions, duplications, dosing inaccuracies, drug interactions, and to observe compliance and adherence patterns. A comparison of existing, previous, added, deleted and changed medication therapies must occur at every transition of care. In a patient-centered process, one must be sensitive to diversity and the patient’s level of health, literacy, cognitive and physical ability, and willingness to engage in his or her personal health care [5].

Non-judgmental, neutral, and open communication skills are necessary for the success of any structure. The intention is to resolve discrepancies in medication regimens and improve patient safety and ultimately the health of the community. In order to optimize success, clinicians must work together, putting community cooperation and partnership foremost, in place of individual territories.

Management

The Joint Commission (TJC - formerly known as JCAHO) has set an expected standard of practice with

the National Patient Safety Goal (NPSG) 8 on medication reconciliation. National Patient Safety Goal

8 is to accurately and completely reconcile medications across the continuum of care. However, since its

introduction in 2005, effective methods to administer and manage have been challenging to implement.

Currently, this finding will not contribute to an organization’s accreditation decision. The intent of NPSG 8 is

the improvement of health care. The Joint Commission recognizes the difficulties and expects organizations

to continue to address medication reconciliation [6]. As of April 2010, the TJC has commenced a field

review [7]. Organizational compliance is an imminent focus.

In one study, a standardized medication reconciliation process using a multidisciplinary approach, academic detailing (targeted one-on-one education), crosschecks, audits, and feedback led to a reduction in medication discrepancies [8]. There are numerous aspects that must be addressed by a multidisciplinary approach and supported by electronic tools. In order to reduce the number of discrepancies, the severity of discrepancies, and the types of discrepancies, a Collaborative Partnership must be created. The Collaborative Partnership would include and involve:

• Senior Administrative Leadership

• Clinical Leadership

• Physician Leader (that is also a Senior Administrative Leader or a respected ‘thought leader’ among the

physician group)

• Unit Nurse Manager

• Staff Nurse

• Pharmacist Manager

• Pharmacy Technician

• Human Resource

• Patients

Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians are an outstanding manpower resource throughout all stages of the medication reconciliation process. At many institutions they have begun performing medication histories for patients at transitions of care. In addition, they continue to enhance the accuracy of patient medication lists by direct entry in the electronic hospital summary (patient profile) [8].

Previous studies have shown that medication reconciliation performed by a pharmacist in the preoperative clinic results in a substantial number of pharmaceutical interventions or in a reduction of medication discrepancies from about 40% to 20%. A reduction of discrepancies by half was also identified in a study in which pharmacy technicians were used to obtain medication histories, suggesting for the first time that technicians could have such a role [9].

Major reductions of medication discrepancies can be achieved by the use of pharmacy technicians supervised by pharmacists. The supervision is not to correct mistakes in the actual medication verification process, but rather to identify additional drug-related problems.

Expanding the role of pharmacy technicians is more than a cost-effective intervention. This approach quantifies the collaborative team, while also enhancing job satisfaction and retention.

Clinical interventions can be successfully assigned to pharmacy technicians and pharmacists, resulting in a statistically significant decrease in medication discrepancies [10].

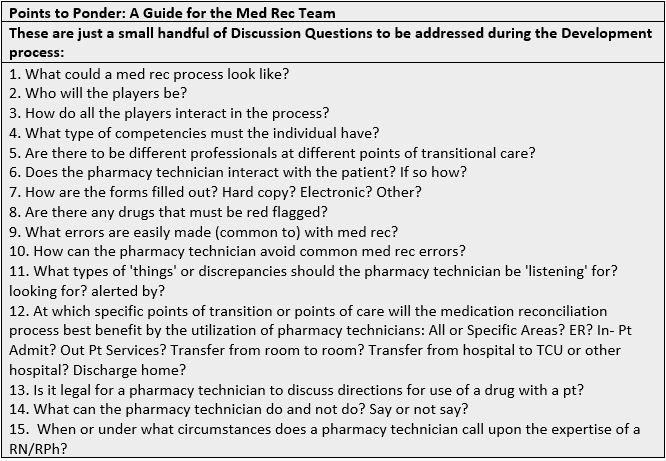

Beta-Test Collaborative Partnership

Hospital admissions, transfers, and discharges occur during all hours throughout the week. Developing and implementing electronic medication recon-ciliation is challenging. In order to establish a starting point, a ‘paper’ retrospective review can be completed. This will establish a given baseline of data for comparison. The Pharmacy Manager can obtain a set of 30 closed patient records with the following parameters:

1. A minimum patient stays of 3 days.

2. A retrospective timeline of 1 to 3 months.

3. Utilization of a random selection process.

4. Review the charts and count the unreconciled medications.

5. Tally the errors and report the data as a monthly number of errors per 100 admissions.

6. Present findings to members of the Collaborative Health Care Team.

The Medication Safety Reconciliation Toolkit developed by North Carolina Center Hospital Quality and Patient Safety, September 2006, encompasses assessment, project, performance improvement model, spreading and formalizing, and reference materials. This Toolkit is highly recommended as additional reading before the commencement of a medication reconciliation process. http://tinyurl.com/2bwmq4a

Once a baseline performance has been established the Collaborative Team begins the difficult task of creating

a system process. Each system is unique to the organizational environment and corporate culture. Suggested

guidelines for initial beta-test resources toward development meetings and tasks are:

8 to10 hrs./week the first 6 weeks of the 6 month beta test

24 to 36 hrs. /month for the remainder of the project

1 to 4 hrs./week for the first 6 weeks of the 6 month beta test, depending on role

4 to 12 hrs./month for the remainder of the project

The majority of the beta-test time will be devoted to planning, creation of forms and the process, real-time undertaking, retrospective study and analysis, user feedback, and establishment of best practices for policies, procedures, and training. This involves repeating the pattern of activities, Plan-Do-Study-Act, until a workable process or system improvement is achieved.

The developed and implemented electronic medication reconciliation documentation process must be adaptable and flexible at this early phase. Requirements for successful implementation include adequately staffed pharmacy personnel to expand the reconciliation documentation process, the ability of nursing and pharmacy to collaborate with prescribers, and the availability of technical support. Until computerized prescriber order entry becomes mandatory, the implementation of an institution’s standardized medication reconciliation process will continue to be delayed [11].

Pharmacy Technicians and pharmacists are uniquely qualified to undertake the lead in the medication

reconciliation process. Any personnel selection process is to include excellent communication and problem

solving skills, training and background reading, competency checklist, observing and shadowing a mentor,

performing supervised interviews, cross-training, maintenance of consistent core personnel, and ongoing

performance competency reviews.

The author has designed and implemented a medication reconciliation process for a local acute care clinic, working with the existing electronic health records system. The process involved a medical assistant, pharmacy technician, and pharmacist. The pharmacy technician was selected based upon superior communication skills and pharmacology knowledge. Patients were triaged to the Pharmacy Intervention Clinic by providers. The medical assistant and pharmacy technician observed ten medication reconciliation interventions conducted by the pharmacist. Once the training was complete and competencies met, the pharmacist observed ten medication reconciliation interventions conducted by the pharmacy technician.

Patients were given health education, medication discrepancies were categorized and documented electronically, and suggested corrections were emailed to the providers. A sample Medication Reconciliation form is provided at the end of this document and may be used or adapted to fit another medication reconciliation system. Outcomes and success stories were shared with the providers.

The role of the medication reconciliation pharmacy technician is not well defined at this time, but rather it is evolving and can be created based on the system’s requirements.

Outcomes

Each year, as more studies are conducted, the literature is revealing that medication reconciliation provides

optimum care. Whittington and Cohen showed a 70% reduction in errors and 15% reduction in Adverse Drug Events over a 7-month period with Medication Reconciliation (Med Rec) intervention [12]. Another

study corroborated with an 80% reduction of potential adverse drug events, within 3 months, in a segmented

population of surgical patients utilizing pharmacy technicians to initiate the reconciling process [13].

Medication reconciliation impacts all four business quadrants, Financials, Product/Services/Quality, Customer Satisfaction, and Workload (eventually). This is hard work. Asking people to change what they have been doing is problematic, but not impossible. The Med Rec team will provide vision, prioritize, focus, and share project data and success stories with colleagues and senior leadership. Ethically, improved medication management is the right thing to do.

Teaching Patients to Take Charge

The role of patients cannot be undervalued. Patients are an integral part of the process. Patients and family

care takers can be taught about the importance of an accurate and updated medication list, including nonprescription

medications and herbal supplements, as well as the necessity of bringing medication bottles or

the most current medication list to every provider visit or hospital admission [14].

Overall, patients voiced a realization of the importance of health care providers and patients working together to ensure a complete medication review. Many times, patients stated that they had experienced medication-related difficulties in the past or were being admitted with medication-related problems. Some patients expressed that they had a family member admitted or discharged with medication-related difficulties in the past [15]. The importance of an up-to-date and readily accessible list of medications cannot be underestimated.

Conclusion

In the coming years, medication reconciliation will become a targeted goal for organizations. The intention

of the Joint Commission is unmistakable. Pharmacy technicians are in a knowledge and experiential based

position to utilize their talents. While organizations create their medication reconciliation health care teams,

some technicians may find an opportunity to become a member of that team. As a team member one will influence

and design their process, and construct a career path for future pharmacy technicians. Equally, as the

practice matures and ripens, pharmacy technicians may have an opportunity to develop employment proposals,

job descriptions, or professional competencies for a medication reconciliation pharmacy technician.

One issue is very clear: together as a community we can create better health care economics and therapeutic outcomes. All heath care partners have a role to fulfill. It takes individuals dedicated to change and the accompanying challenges, frustrations, and successes to initiate this process. In addition, the growth of the individual in self-competency skills assessment, knowledge based pharmacology, communication, and diversity are key. Innovations, initiatives, and intelligently designed systems will provide form and structure. Appropriate utilization of technology and a network of health care team members are key contributing factors in implementing medication reconciliation in the healthcare system.

Sociodemographic Aspects

• Haig, K. R. N. (2003). One Hospital’s Journey Toward Patient Safety - a Cultural Revolution. Medscape Money & Medicine, 4(2). • Pronovost, P. (2003). Medication Reconciliation: A Practical Tool to Reduce the Risk of Medication Errors. Journal of Critical Care, 18(4), 201-205.. • Rogers, G., et al. (2006). Reconciling Medications at Admission: Safe Practice Recommendations and Implementation Strategies. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 32(1), 37-50. • Haig, K. R. N. (2003). One Hospital’s Journey Toward Patient Safety - a Cultural Revolution. Medscape Money & Medicine, 4(2).

Additional Reading

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nurseshdbk/docs/barnsteinerj_mr.pdf

Patient Safety Network /Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.gov

http://psnet.ahrq.gov/primer.aspx?primerID=1

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

Endnotes

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!