Biography

Interests

Dr. Carlo Lazzari

Centre for Healthcare and Medical Education, United Kingdom

*Correspondence to: Dr. Carlo Lazzari, 19 Castlemoat Place, Corporation Street, Taunton, TA1 4BB, United Kingdom.

Copyright © 2018 Dr. Carlo Lazzari. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Short Communication

Partnership in dementia care is becoming one of the primary goals of the actual healthcare system in the

United Kingdom. Besides, as multidisciplinary teams are constantly involved in the care plans, it becomes vital

to ensure that all people occupied in the care of patients with dementia (PwD) understand the requirements

for collaboration and care planning. The current study will also serve as policy paper to implement a patientcentred

approach to dementia care. Several constraints exist for a coordinated care planning and the sharing

of expertise and skills within interprofessional teams. The primary limitations are linked to the nature of

care of PwD which is complicated and long-term. Also, there are different interfaces of teams that might

have some difficulty in communicating data, plans, notes, as these teams are geographically unconnected,

have a different philosophy of patient care, operate in an asynchronous matter, and work according to silos

management strategies. For instance, the communication within wards when a patient with dementia is

transferred often sees delay in getting the notes about the new admission. The discharge letters from the

previous admissions might not be ready when a patient arrives at a new unit. The medication cards are not

always updated or communicated within interlocking teams. The original team might be late in generating

all the information needed in the new ward when the patient was already transferred. Chronic medical

conditions might be recorded in the family doctors notes but are not in the file accompanying a patient

during admissions. Occasionally, in order to facilitate the allocation of a patient to another destination, some

negative behavioural or clinical aspects are emphasized or omitted to increase the likelihood to appeal the new team. Interprofessional teams in the care of PwD involve many healthcare workers regulated by

specific professional bodies: nurses, doctors, clinical psychologists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists,

clinical managers, support workers, etc. Hence, due to the complexity of clinical cases of dementia and to

disparities in professional figures, collaboration, coordination, and mutual trust are not always automatic.

In fact, divided staff need specific training in order to grow and to operate in partnership in the care of

PwD. The first goal in partnership responds to the theory of social systems. Teams can avoid becoming

chaotic (hence impairing patient care) as long as the barriers within systems are permeable to exchanges

of information via interprofessional communication. This action will avoid the risk of that PwD remain

unattended in one of their basic needs because two systems (wards, teams, hospitals) did not communicate

some essential information in patient care (e.g., an allergy to medication). Another interprofessional barrier

to the partnership is the conflict within different professions. For instance, PwD might have a reduced

quality of care because a hospital manager does not accept that PwD’s agitation is treated with medication

as instead suggested by the medical team. Another barrier to a partnership is found when teams operate

asynchronously, during different times of the day, of the week or from different regions. For instance, PwD

might receive limited night sedation because the night team did not hand over to the day team about

increased confusion and agitation during night time and insomnia of ward patients. Another problem found

is that when patients are transferred from one geographical region to another, the whole team changes, and,

consequently, the care plans promoted in the former hospital or ward cannot be replicated in the new ward

or unit. In this case, the entire care plan needs to be regenerated. Another barrier to a partnership is found

in the models adopted by the professionals to describe and treat a symptom or presentation, and when the

interprofessional team cannot see coordination of the different care models. For instance, a consultant in

dementia believes that patient’s confusion should be treated ‘mainly’ pharmacologically while the clinical

psychologist believes that it should be treated ‘mainly’ with cognitive behavioural therapy. In this case, the

two professionals could have implemented a coordinated plan in the partnership where the patient is treated

pharmacologically ‘and’ with cognitive behavioural therapy. However, the divide has not been filled. In

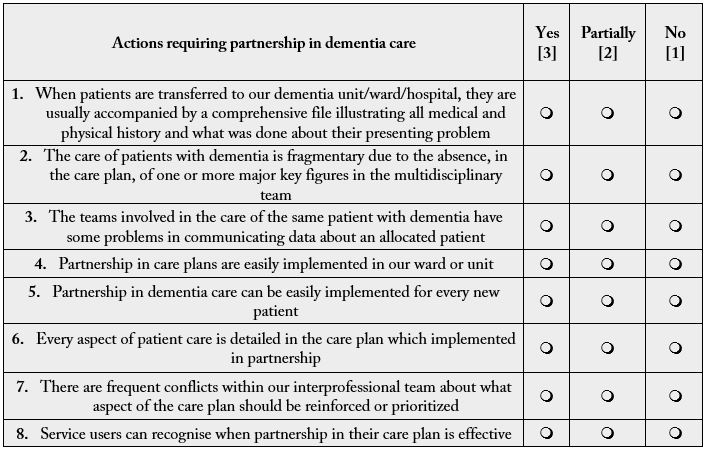

auditing partnership and coordination in PwD care the author of the current article has created a checklist

for assessing interprofessional care plans, the Partnership in Dementia Care Scale (PDCS). In the scale,

answers indicate that the patient has or not a robust care plan and that partnership in care is implemented.

There are several advantages of partnership in dementia care [1]:

1. ‘Added value’ as the global care plan cannot be accomplished if healthcare professionals work as separate entities.

2. ‘Reciprocity’ as the cooperation benefits each member of the multidisciplinary team.

3. ‘Formal and ongoing relationship’, a partnership is progressively achieved by working together.

4. ‘People who use services’, a partnership is effective only if it is recognized by the service users.

5. ‘Partnership is voluntary’ based on confidence, fairness and acknowledgement of the alliance.

Moreover, a patient centred care is achievable by sharing accountability and leadership within the interprofessional team [2]. Besides, being able to ask for help and to provide support to other members of the interprofessional team is one of the strategies of active collaboration [3].

Partnership in dementia care and interprofessional teamwork covers all areas of PwD treatment [4]:

1. Conclusive diagnosis is reached by consensus of different team members of what is the underpinning

problem.

2. Conclusive treatment requires coordination of each member of the team to assess the effect, side effects, and

allergies to the treatment provided.

3. Conclusive placement requires coordination of home treatment teams, families, care coordinator, support

workers, commissioners, and hospital team that agree what the best regarding therapy and placement for a

patient.

4. End of life care requires knowledge of hospital assets, wishes of the family, limitations linked to patient’s

physical health, and the legal aspects of DoLS (Deprivation of Liberty Safeguarding) and DNR (Do Not

Resuscitate).

The current project respects the guidelines for policy papers in the following dimensions [5]:

1. ‘Effectiveness’. The proposed paper examines the major steps in promoting partnership in dementia

care as matured during practical observations and auditing of dementia wards operating according to

multidisciplinary models.

2. ‘Efficiency’. The social impact is significant as it includes the whole care of a person with dementia.

3. ‘Equity’. The aim is to reduce the social divide in the health provision and provide PwD with the best care

plans operated by multidisciplinary teams.

4. ‘Feasibility’. Partnership in dementia care is already implemented in some regions and frequently applied

in the wards and community treating patients with dementia.

5. ‘Flexibility’. Care plans implemented by a partnership in dementia care should be open to the expertise

and creativity of each member of the multidisciplinary team.

In conclusion, the present article also stands as a policy paper for the management of patients with dementia in terms of desired actions in partnership care and eexpected goals in quality of patient-centred care.

Conflict of Interest

The author of the current article expresses no conflict of interests in the disclosed contents.

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!