Biography

Interests

Uzoma Kizito Ndugbu* & Uchechukwu Chukwuocha, M.

Department of Public Health, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Nigeria

*Correspondence to: Dr. Uzoma Kizito Ndugbu, Department of Public Health, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Nigeria.

Copyright © 2018 Dr. Uzoma Kizito Ndugbu, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Nigeria has the largest number of malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea-related deaths. While it

is important that the country attains universal coverage of key childhood illness interventions,

poor attention is given on the implementation ICCM in drug shops, where close to a third of the

population seek health care.

The ICCM seeks to manage and control the rampaging effects of malaria, pneumonia and

diarrhoea among children in low-income countries, this study thus evaluates the outcome of

care given at drugs shops following the intervention of ICCM in the management of childhood

illnesses.

A total of 17 drug shops were sampled at Ulakwo and another 20 sample at Emii, Imo state

Nigeria. ICCM equipment was made available to the drug shops and additional training was

offered to the drug shops at Emii as in form of intervention. They were both assessed at baseline

and endline using a questionnaire.

Those who were taking the proper diagnostics were 54% while 86.4% were given the proper

medicines. Up to 62% recorded the age. At baseline, the drug shop dealers were not keeping

proper record of information about the patients but they improved with intervention from 15%

to 45% in both paper and computer recoding at post training survey.

The results of this study highlighted the need for a more proactive utilisation of iCCM strategy

in the communities with the provision of training, materials, supervision and logistic. Since most

care givers sought care at drug shops, it is important to give constant iCCM training among drug

shop sellers.

Introduction

Globally, there has been an obvious effort to combat and reduce under-five mortality. Progressive as these

efforts are towards the then MDG target of a two-thirds reduction of 1990 mortality levels by the year

2015, it is unfortunate that the proposed SDG target of 25 deaths per 1,000 live births by 2030 may not be

attainable. This is the case when there are an estimated 5.9 million children of under-five deaths in 2015,

with 16,000 deaths every day, of 43 deaths per 1,000 live births [1]. Of these deaths, three quarters are from

the three main childhood killers - malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea [2]. What makes these cases very

unfortunate is that these are preventable and treatable diseases.

Truth is, even though there has been a noticeable reduction in malaria child mortality, of 26% in Africa [3] due to increased deployment of long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLITNs), increased availability of highly effective artemisinin-based therapy and improved diagnosis of malaria, the Roll Back Malaria (RBM) partnership target of 80% of malaria patients receiving effective treatment within 24HRs cannot be achieved in sub-Saharan Africa where antimalarial drugs are still confined to the formal health sector [4,5,6]. Also, the estimated 760000 deaths from diarrhoea, and of 920,136 deaths from pneumonia among the under-fives [7], together with poor access safe drinking water, zinc supplements, intravenous fluids, rotavirus, Hib, pneumococcus, measles and pertussis immunization, amoxicillin dispersible tablets, oral antibiotics have continued make any integrated global action for the control and prevention of these killer diseases will be long [8].

Surely, it is important to note that in a bid to ensure increased access to treatment; the Integrated Community Case Management was adopted in 2000. It is an action approach that is poised to be an effective strategy of providing pragmatic support to access, classify and attend to sick children suffering from the three childhood killer diseases of malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea; at the community level. The ICCM whose basic packaged consists of Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and Artemisinin combination-based therapy (ACTs), Respiratory timers and dispersible amoxicillin, and low osmolarity ORS and zinc; received a boost in its determination to provide an enduring action against the three childhood diseases when the place of community health workers, of grass root health providers was identified as being vital [9].

As such, multi-country evidences have shown that utilisation of ICCM strategy of training Community health workers, providing them with materials, supervision and logistic support have contributed to bring a noticeable reduction in under-five mortality in countries where they are adopted: Bangladesh, Zambia, Ethiopia and Malawi [10,11,12,13]. The ICCM with time ran into hitches in its programmes with systems that were operational to the communities, ranging from poor funding, poorly trained and committed workers and poor attitude to public health sector. And so there was need to fill the gaps in the understanding of the optimal approaches to the implementation, scale-up, and sustainability of ICCM programmes and address the new questions: the role of the private sector in the ICCM project, the assessment of the quality of care at the rural and remote settings, the determination of the adherence to treatment guidelines among health workers at the community level, especially given the ugly trend that health workers often provided treatments for febrile children with RDT-negative test results [14], and the potential contribution of providing improved diagnostic and treatment approaches (especially for presumed pneumonia) through ICCM and rational use of drugs [15]. There was need then, to bring in the private sector health providers, if ICCM must meet the target people.

Reviews of the available literature reveal that shops are often preferred to health facilities as a first treatment action [4,16]. Retailers tend to be more accessible, have longer and more flexible opening hours, are willing to negotiate charges and offer credit, are politer and friendlier and are generally perceived as being cheaper. Patients also seek treatment in the private sector out of necessity since public health facilities experience frequent stock-outs. However, the private retail sector is often poorly regulated in low and middle income countries.

In Nigeria, malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea are still responsible for more than 50% of death among children under five years old. What is hard to know about this is that majority of the febrile children, particularly those living in remote areas, die at home. The adoption of ICCM of pneumonia, diarrhoea and malaria by Nigeria has only been implemented in two states, Abia and Niger; through the Rapid Access and Expansion (RAcE) project. RAcE 2015 is an ICCM project funded through the WHO Global Malaria Programme (GMP), with the support of the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD) to support case management of diarrhoea, pneumonia and malaria in children aged 0 - 5 years at the community level [1].

This effort is greatly hampered by the barriers of finance, extended family networks (which increases the tendency of administering home-based remedies such as herbs or a plain water enema), limited knowledge about causation and prevention of childhood illnesses, lack of strategic and targeted health education at community level, divergence between care-giver and care-seeker roles and supply-side issues [17].

Common opportunistic practices include illegal stocking of prescription-only medicines, the use of unqualified staff and referral by health facility staff to private outlets in which they have a financial stake [18,19]. The introduction of ACTs, amoxicillin dispersible tablets and zinc tablets compounded the problem further. In absence of regulation people are likely to buy cheaper and less effective drugs from the private retail sector [20]. Furthermore, the misuse of ACTs, amoxicillin and zinc tablets and, the use of artemisinin monotherapies, for example, could contribute to the emergence and spread of artemisinin resistance.

The continued increase in deaths of under-five children from malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea is an actioncall invitation for the ICCM project in Nigeria to make a decisive entrance in the private sector – clinics and drug shops. With the reality of up to 85% of parents in Nigeria, who seek care at private sector health facilities, especially drug shops [21,22]; and drug shop sellers have been observed to behave primarily as commercial salesmen, since around 75% simply sell what a customer requests, and on other rare occasions, fills a prescription [23], there is an urgent need to integrate them into the global health action against the control and prevention of the three childhood killer diseases of malaria, pneumonia, and diarrhoea.

Materials and Methods

The study design was a quasi-experimental study using an intervention town (Emii) and one comparison town,

Ulakwo. This is because while randomized controlled trials have high internal validity when determining

efficacy of an intervention, they are often not feasible or acceptable and their results are rarely enough

without additional contextual information and economic evaluation. The overall study design was a quasiexperimental

study using one intervention town (Emii) and one comparison town (Ulakwo). We collected

data in the intervention and comparison districts twice, both before and after introducing the intervention

(ICCM) in Emii, in order to determine its effect on quality of care.

All two studies were done in eastern Nigeria, the two rural towns of Emii and Ulakwo located around

404km and 520km respectively; southeast of Owerri, Imo State capital. From the 2006 population census,

the two rural towns are estimated to have about 120, 000 and 103, 000 people, with geographical coordinates

of 5*27’40’’N 6*8’30’’E and 5*24’43’’N 7*7’32’’E (Wikipedia. Imo State.http://en Wikipedia.org/wiki/imo

state.) respectively. Emii is made up of ten villages, while Ulakwo has ten villages. People of both rural towns

are mostly farmers, traders, civil servants as well as professionals like teachers, lawyers, doctors etc. Both

rural towns have tropical wet climates. Rain falls for most of the year with a brief dry season. The harmattan

affects the towns in the early periods of the dry season. The average temperature in both towns is 24.4*.

The ecology of Nigeria varies from mangrove swamps and tropical rain forest belts in the coastal areas to open savannah woodland on the low plateau - which extends through much of the central part of the country - to semi-arid plains and Sahel grassland in the north and the eastern highlands. The seasonality, intensity, and duration of malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea transmission vary according to the different ecological strata [24].

The choice of the two rural towns was purposive. This was informed by the predominance of child mortality rate of under-five from child illnesses in the area, side by side the reality of seemingly strategic drug shops.

The study population includes all children less than (<5 years) five years of age, living within both study

areas. Also included are the parents or care-givers of the children who sought care for their children less

than five years at the drug shops in the study areas within the one year of the research study, and the drug

shop sellers in the study areas.

All registered drug shops in both towns were included in the intervention study. The main components

of the programme was training of drug shop sellers, community awareness campaign (inter-personal

communication, public announcements at gatherings: market squares, town-hall meetings, churches etc.)

and monitoring and evaluation of the programme.

Considering the vital role traditional administration and political leaders play in ensuring community participation, and successful implementation of an intervention programme; a series of sensitization meetings were held in the community. Having obtained the support of the community leaders, meetings were held with members of drug shop sellers to gain their cooperation. Appreciable trust was built with them during the beginning phase of the project.

With the help of a graphic artist, we developed posters containing clinical symptoms of malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea dosages of approved ACTs, and tablets; and treatment advice in English and Igbo languages to communicate guidelines to drug shop sellers in diagnosing severe malaria, pneumonia, diarrhoea requiring referral, and to motivate the consumers to go for approved ACTs drugs, zinc tablets and amoxicillin tablets.

Before the intervention, focus group discussions (FGD) and in-depth individual interviews with drug shop sellers was conducted.

To determine the nature and appropriateness of care and effect of intervention, care-seekers were selected as

they entered and exited the selected drug shops in the two towns of Emii and Ulakwo. At the baseline, we

had 94 (39 at the baseline and 55 at the endline interviews) and 104 (62 at the baseline and 42 at the endline

interviews) respondents who visited the drug shops in Ulakwo and Emii respectively during the study.

A census of all registered drug shops was in the study areas was taken with the assistance of the chairman of the local Drug shop sellers association and thirty-seven drug shops were identified by the Yaro Yamani sample size formula from the population of 41.

Where N is population size

n is sample size

e is coefficient of margin, which is 0.05

Questionnaires completed were checked for completeness by counting the number of those returned with

the pages intact and they were checked for consistency by making sure that responses given by a respondent

in a questionnaire do not contradict each other. The data was cleaned and analyzed using SPSS statistical

packages version 15. Results were presented using appropriate charts and tables. Class variables were

presented on tables of distributions, which were expressed in percent. The mean summary statistics were

computed for continuous variables. Chi-square test was used to test for any significant association between

adherence-assessment factors at baseline/endline, at 5% significant level. Probability value (p) was used to

assess significance and a p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

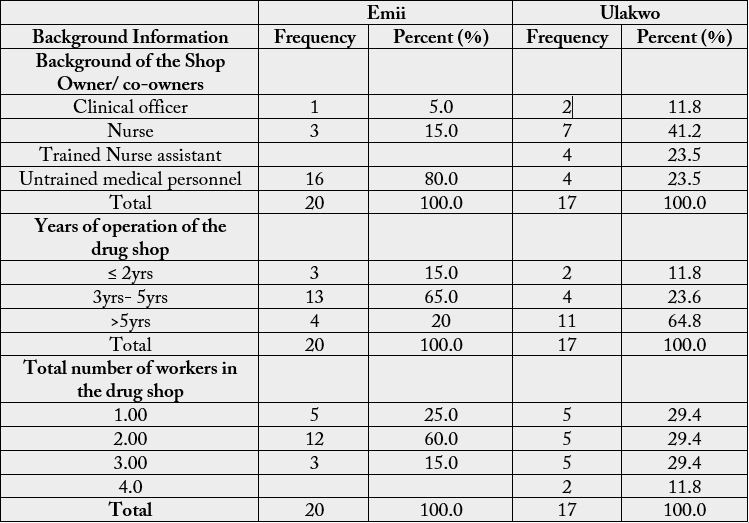

There were a total of 37 shops used in the study, of which 37 were sampled from Emii community and the remaining 17 were obtained from Ulakwo community. From Table 1, for the Emii drug shop owners, majority (80%) of the shop owners were not medically trained, 15% were trained nurses. At Ulakwo drug shops used for the study, 41.2% and 23.5% were respectively owned by nurses and trained nursing assistants. Up to 13 (65%) of the drug shops studied in Emii have been operating for 3 - 5 years, with only 3 (15%), operating within 2 years or less. On the other hand, 11 (64.8%) of the drug shops selected from Ulakwo have been operating for over 5 years.

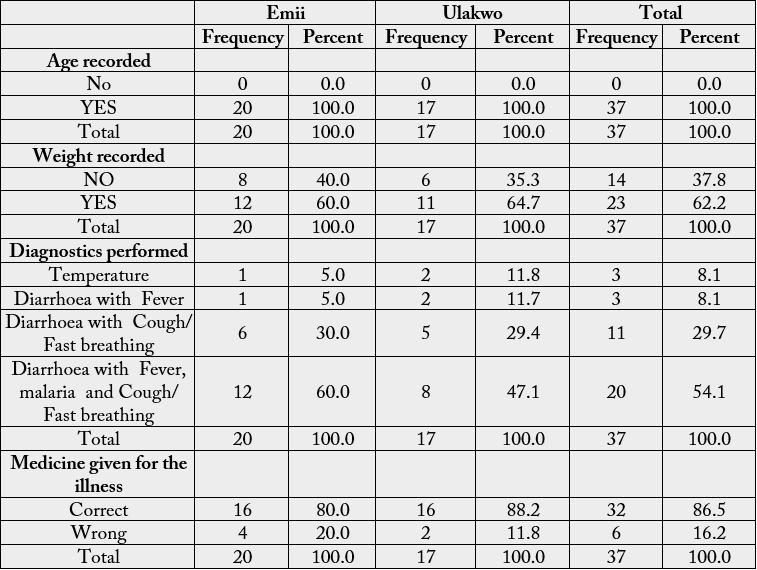

From Table 2, at Emii, all the drug shops recorded the age of the under-fives children while 60% of them recorded the weight of the children. Up to 60% performed diagnostics for diarrhea with fever and cough/ fast breathing, 30% of the diagnostics performed were on Diarrhea and cough/ fast breathing, while only 30% each were on diarrhea with fever and temperature alone. There were a total of 80% that offered the correct medicine while up to 20% offered wrong medicine to the illness.

Similar results were obtained at Ulakwo. For instance, 35.3% do not record the weights and over 11% give the wrong medicine for the illnesses (Table 2). The output for the overall grades in the studied area was also recorded on Table 2.

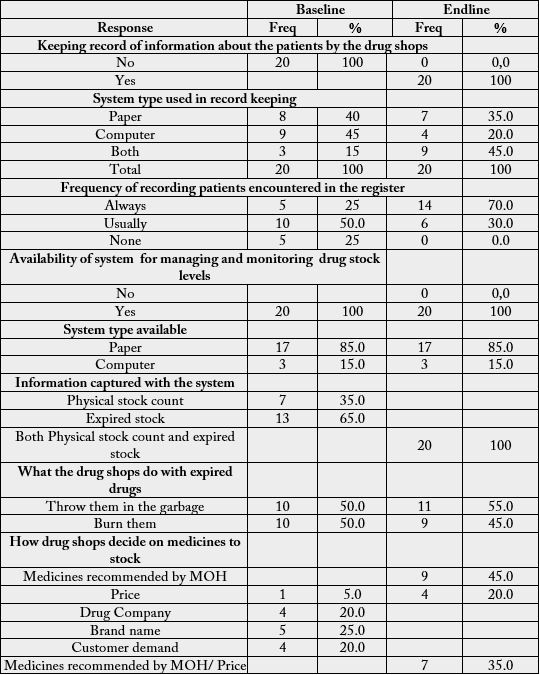

In Table 3, none of the drug shop dealers studied was keeping record of information about the patients by the drug shops before the training but after the training, the endline result indicates that all of them are now keeping record of information about the patients by the drug shops. Only 15% of them were recording information on both computer and paper prior to the training, and the percentage improved to 45% after the training. The frequency of constant (always) recording patients encountered in the register also improved from 25% at baseline to 70% at endline. No change was recorded on the availability of system for managing and monitoring drug stock levels as all the respondents responded “yes” in both cases at baseline and endline.

Only 35% of the Physical stock count were captured in the system at base line, but at end line, all Physical stock count and expired stock were been captured in the system. Not much difference was observed in terms of what the drug shops do with expired drugs at endline.

The decision on medicines to stock in the drug shops were up to 25% based on brand name at baseline but at the ensline, 45% and 35% respectively were based on medicines recommended by MOH and the medicines recommended by MOH in combination with the price.

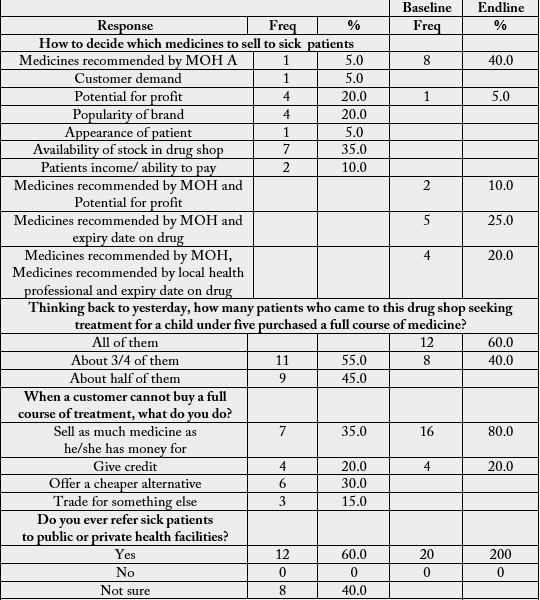

None of the patients who came to the drug shops seeking treatment for a child under five purchased a full course of medicine at the baseline but remarkable improvement of 60% was obtained at the endline.

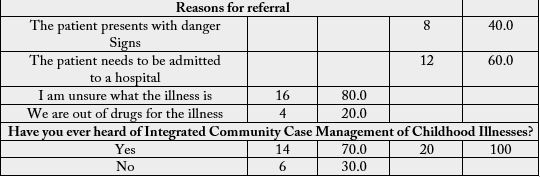

At baseline, 80% of the drug shops will only refer the patients to a public health facility if they were not sure of what the sickness of the patients is but at endline, up to 40% and 60% respectively will base their decision of patient presents with danger signs and if they feel that the patient needs to be admitted to a hospital. There were 30% that have not heard of Integrated Community Case Management of Childhood Illnesses but after the training, all the drug shops are now aware of it.

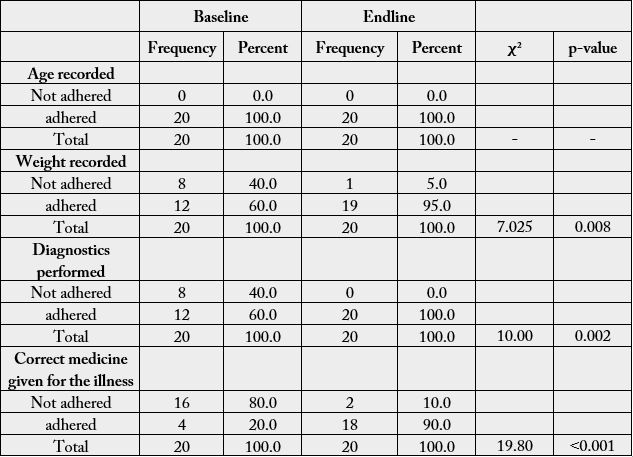

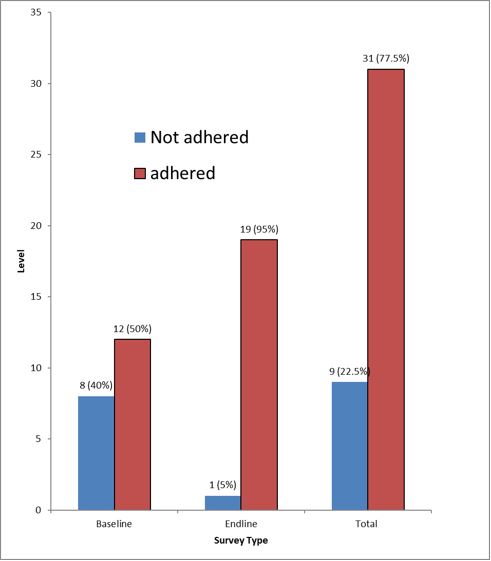

Finally, the adherence to treatment guidelines on the management of malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea for the under-fives among trained drug shop sellers was such that significant improvements were recorded, after the training. In terms of weight recoding, adherence significantly increased from 60% to 95% (p value = 0.008, χ2= 7.025). Similar results, were obtained at diagnostics at 100% (p value = 0.002, χ2= 10.0), and administering of correct medicine at 90% (p value = 0.001, χ2= 19.80) (Table 4). The summary of the adherence level indicates that the overall adherence improved from 50% at baseline to 95% at endline (Figure 1).

Discussion

This study was primarily aimed at evaluating the integrated community case management for childhood

illnesses in care given at drug shops in Owerri North, Imo State, the aim of the study was successfully

achieved. In respect to the quality of care provided by private sector drug shops when treating childhood

malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea all, those who were taking the proper diagnostics were 54% while 86.4%

were given the proper medicines. Sixty-two percent were recording the age. While these values seem to be

high, it also indicates that some non-negligible gaps exist in the administration of quality care. The findings

in this study are in line with the results in Awor et al., [25] for which 88% of febrile children who visited

the drug shops with fever, cough and diarrhoea were appropriately managed according to ICCM protocols.

Since most care givers sought care at drug shops for reasons such as accessibility, affordability, deferred

payment and others, it is important to give ICCM training among drug shop sellers.

At baseline, the drug shop dealers were not keeping record of information about the patients but the training helped them in doing so. They also improved on information recoding as up to 45% were found to be recording the in both paper and computer at post training survey, marking an improvement from a low value as low as 15%. Reasonable number of them was also started recording patients encountered in the register on regular bases at post training survey. Hence considering the fact that the rate of malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea is still high in Nigeria and other developing nations, the findings in this study probably suggest that will bring proper implementations of ICCM, will depict a remarkable reduction in the level of mortality and morbidity that usually accompany such diseases especially among under-fives.

On the contrary, two studies [22,2], found that the impact of ICCM on the care of childhood diseases, especially malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea had remain little.

The results of this study has highlighted the need for a more proactive utilisation of ICCM strategy in the communities with the provision of training, materials, supervision and logistic; these findings have shown consistency with some other studies in other places around the world [10,11,12,13]. It has also underscored the need towards encouragements of private drug shop dealers in the implementations of ICCM.

Only 35% of the Physical stock count were captured in the system at base line, but at end line, all physical stock count and expired stock were being captured in the system. Not much difference was observed in terms of what the drug shops do with expired drugs at endline.

The decision on medicines to stock in the drug shops were up to 25% based on brand name at baseline but at the endline, 45% and 35% respectively were based on medicines recommended by MOH and the medicines recommended by MOH in combination with the price.

None of the patients who came to the drug shops seeking treatment for a child under five purchased a full course of medicine at the baseline but remarkable improvement of 60% was obtained at the endline.

The adherence to treatment guidelines on the management of malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea for the under-fives among trained drug shop showed significant improvements on post training survey, with the overall adherence level increasing from 50% to 95%. In a Ghanaian study, adherence to dosing guidelines was high, among CHWs’ though adherence to referral guidelines was low [26]. Adherence was also high among health workers in registered drug shop [27]. The likely reasons to that were that training, re-training and gives important knowledge and skills [28,29,30,31], which are required for quality care in ICCM implementation.

Conclusion

The results in this thesis confirm that drug shops were the first source of health care for almost half of the

sick children in rural Nigeria, but the quality of care they provided was poor. However, with the introduction

of the ICCM intervention at registered drug shops, it was possible to greatly improve the quality of care that

children received. There was high uptake and utilization of diagnostic tests for malaria and pneumonia by

drug shop attendants; large improvement in appropriateness of care for malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea

in children both at the drug shop level and at population level; and high drug seller adherence to treatment

protocols. The results provide good evidence that drug shops can be utilized to expand access to point-ofcare

diagnostics and appropriate treatment for malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea in children. This could

contribute to reduced morbidity and mortality in children, from these illnesses.

Truth is, the integration of drug shop owners in the Integrated Community Case management of childhood illnesses can be increased not just access to high-quality health care, but also with appropriate training and monitoring ensure that prompt and appropriate medicines and treatment are given and received to the underserved; consequently, reducing deaths among the under-fives throughout Nigeria.

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!