Biography

Interests

Ray Marks

Department of Health and Behavior Studies, Columbia University, Teachers College, New York, USA

*Correspondence to: Dr. Ray Marks, Department of Health and Behavior Studies, Columbia University, Teachers College, New York, USA.

Copyright © 2021 Dr. Ray Marks. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

The COVID-19 virus, which persists in heightening premature death rates among older adults, especially those with health challenges, also appears linked to possible poor outcomes currently observed for older adults who not only experience COVID-19 infections, but who may experience highly injurious falls that lead to bone fractures. This overview focuses on falls injuries, the chief hip fracture precursor, and the possible impact of pre existing or concurrent depressive symptoms, especially among those treated with anti-depressant drugs, on falls risk, as well as COVID-19 risk. Reviewed are relevant topical articles and past literature and research on these topics located in the PUBMED data base. Results show, a large body of prior work on falls, but almost none either on falls and their possible bi-directional link to COVID-19, or COVID-19 restrictions, and an array of unanticipated adverse outcomes. Even less attention is paid to the potential role depression may play during this pandemic period and beyond that may heighten falls risk, as well as COVID-19 infection risk, and in turn, hip fracture risk associated with high mortality rates among those infected by COVID-19. Urgent attention to the possible interactive role played by reactive depression, as well as better preventive treatments directed to the origins of co-existing depression, other than anti-depressants appear indicated.

Introduction

A wealth of literature shows that falls and fall injuries continue to produce multiple adverse health care

outcomes and high costs among older adults, regardless of country of origin [1,2]. Strongly associated with

high hospitalization usage and costs [2], premature disability [3], and even death [4], falls thus remain a

highly significant health concern in the context of aging societies in all parts of the globe [5-7]. At the same

time, research has shown that while falls affect more than a quarter of older adults (age 65+) years and above,

there are certain contributory factors, such as excess medication, that are clearly modifiable. These factors are

thus of great interest to examine and to validate, and include a host of physical, cognitive, and environmental

factors.

In this regard, while this current topic is not new, and falls preventive programs do exist in efforts to produce efficacious health outcomes [8], the falls burden remains considerable nonetheless among older socially isolated community dwelling older adults. At the same time, the risk factors for falls as well as recurrent falls may have recently been heightened, along with excess frailty, closely aligned with the risk of acquiring COVID-19 infections. In turn, COVID-19 disease, which can be debilitating for extended periods of time, may increase the risk for injurious falls, in addition to fostering a reduced life quality, a loss of independence and an impaired ability to function physically [9].

In short, unforeseen demands placed on isolated elders, along with excess fears and possible loss of confidence and wellbeing, may be expected to not only impact overall health, but muscle and bone health status as implied by Goto et al. [10], and Gonzalez et al. [11], especially in the face of any pre existing depression in a negative way [12]. As well, even if the older adult is deemed to be healthy, the multiple unanticipated impacts of concurrent services losses, closures and delays, including diagnostic delays in the face of the COVID-19 [13], may similarly be inducing higher than desirable rates of general health declines, and other negative outcomes such as depression, as well as a higher falls risk [13].

However, although many papers currently report on COVID-19 and related determinants among older adults and several multi component falls prevention programs have emerged over time to minimize home based falls risk among older adults, not only do these fail to discuss what can be done about this situation at this pandemic time period, but whether any of these existing multi component approaches will prove efficacious if undertaken during this pandemic, even if implemented as planned is not known. Moreover, can falls induce health challenges inadvertently, for example frailty, and depression, both significant falls risk factors, in their own right.

Clearly, traditional home assessments, renovations, educational classes or materials, and guided interventions, while of import, may not only be prohibited, prohibitive, or scarce at present, but complex and costly as well time consuming and as unsafe. Moreover, even if available, fears of COVID-19 may deter older adults from both seeking care as well as receiving care, and the care needed may not be forthcoming if current directives focus primarily on physical factors, and fail to carefully screen for depression risk as well as falls risk.

In this regard, we elected to examine the most recent available data concerning depression and falling as posted the PUBMED data base, using the key terms: Depression, Aging, and Falls Injuries, COVID-19 and Depression.

Of specific interest was whether:

1: Falls and depression are related, such that older depressed adults are more likely to fall than non-depressed

older adults.

2: Depressed older adults who use antidepressants are likely to fall more often than those who do not.

3: COVID-19 is associated with symptoms of depression in the older isolated community dwelling adult.

4: Frail older adults are more likely to fall and injure themselves as well as develop COVID-19 than robust

older adults.

Methods

After searching the PUBMED database to identify works published predominantly from 2015-2021 items

that discussed either some relevant potentially modifiable falls risk determinants, or the observed link

between depression, and falls risk, as well as articles related to COVID-19 those deemed of interest were

examined more carefully.

The search was limited however, by excluding studies detailing nursing home or hospital-based populations or interventions, populations younger than 65 years of age, and those that did not directly address the current topics. All forms of study were deemed acceptable if they appeared to address one or more items of specific present interest. After examining the data, a narrative overview of what emerged from the search was generated.

Results

The current literature search revealed many stand alone COVID-19 and falls injury articles, a fair number

on some aspect of depression and falls, but only a very few articles on falls injuries relative to COVID-19.

Many articles focused on nursing home or long-term care setting, even though a high number of current

falls appear to have taken place predominantly in the home [14]. Many researchers in the past have however,

pursued studies of falls injuries in older adults that highlight a link to depression that may be of current

relevance to revisit as identified below.

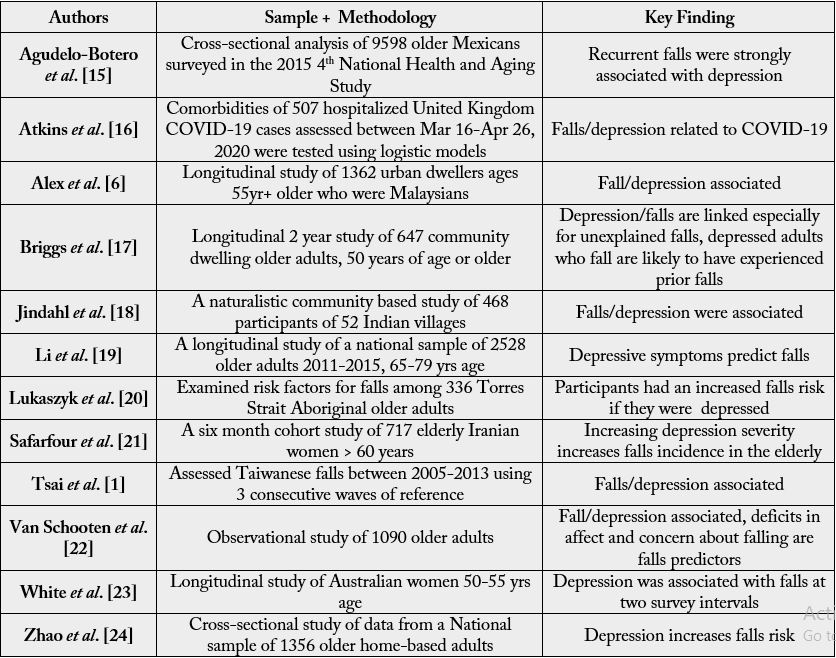

As outlined in Table 1, which represents a high percentage of available publications listed on PUBMED over the time periods of 2016-2021, and bearing in mind that contrary studies may not have been published over this period, it appears safe to say that among the numerous falls risk factors that have been documented over the course of time among cohorts of older community dwelling adults, there appears to be a consistent link between the presence of depression and the risk of falling or incurring one or more recurrent falls. However, this linkage is not unidirectional in all cases, and can arguably be shown to be bi-directional, rather than unidirectional, as recently suggested by Atkins et al. [16] and confirmed by van Schooten et al. [21]. As outlined by Choi et al. [25], however, who examined this issue using data extracted from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) Waves 5 and 6, it does appear that depressive symptoms assessed at baseline are likely to be significantly associated with a greater odds of future multiple falls, as well as increasing falls or continuing falls incidents among those older community dwellers with higher depressive symptoms and probable major depression.

In addition, Trevisan et al. [26] who examined the association between injurious falls and older adults’ cognitive function in order to examine the role depressive mood and physical performance might play in the context of falls found analogous results. That is, injurious falls were associated with the presence of a cognitive decline in older adults that increased with the occurrence of two or more falls, and where depressive mood explained a fair percentage of the association between falls and cognitive decline.

As discussed by Chen et al. [27] in their bibliometric analysis on trends in accidental falls among older adults, there does appear to be a significant association between depression and falling in older adults. Ooi et al. [28] too observed that high rates of depression were associated with the risk of incurring occasional falls among older community dwelling adults, as did Kim et al. [29]. Indeed Kim et al. [29] found significant rates of depressive symptoms in those older adults with reported falls related experiences when compared to those with no-fall experience. In those 64 years or younger and 65 years or older, the odds ratio of presenting with depressive symptoms in the context of a falls experience were markedly higher than those with no-falls experience. In males and females, the odds of depressive symptoms in those with a falls experience was 1.47 times higher (p 0.008) and 1.34 times higher (p =0.000) than those with no-falls experience, respectively.

In particular, in addition to those well documented multiple falls risk factors, such as impaired mobility, vertigo, alcohol use, fear of falling, history of falling, the presence of osteoarthritis, and having a visual and/ or hearing impairment, depression appears to be a highly consistent factor that warrants attention in this regard as identified by Joseph et al. [30] and discussed by Zhou and Xue [31] and Jindal et al. [18]. This association, while not necessarily a linear or uniform association, for example, the risk of incurring a fall in one study was higher among the female elderly population than men in the presence of depression [32], it does appear depression is not only associated with subsequent falls, future osteoporotic fractures, more fracture pain, and lower life quality post-fracture, but is a significant independent predictor of falls risk in the elderly population [18,19,31,32].

Other data show depression among older community dwelling adults, for example that occurring in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns and social isolation impacts [30], may inadvertently influence falls risk through its negative effect on sleep quality and duration, which is related to falls [33]. In turn, the experience of one or more falls incidents, followed by fear of falling and a tendency to decrease one’s social interactions, can similarly result in various degrees of increasing social isolation [34], plus anxiety and depression in their own right [35]. Falls that elicit sedentary rather than active behaviors, may similarly engender feelings of tiredness, as well as anxiety and depression, which are predictors of both physical and psychological declines, as well as long-term physical disability, and severe dependency [35,36]. Even when controlling for baseline physical functioning, vision, chronic conditions, and social support and neighborhood social cohesion, Hoffman et al. [37] found a 0.5 standard deviation increase in baseline 2006 depressive symptoms, one of the most common mental disorders and an up-surging worldwide health factor [38], to be associated with a 30% increase in fall risk within two years.

Moreover, Atkins et al. [16] found older depressed adults to not only exhibit associated COVID-19 infections requiring hospitalization, but many also had a falls and fragility fracture history. In addition, Robb et al. [39] have reported finding a definitive link between being considered to be social isolated during the current pandemic lockdowns and an increased risk of feeling excess anxiety and depressive symptoms among older confined adults. As well, research by De Pue et al. [40] has revealed that depression is strongly related to reported declines in activity levels, sleep quality, well-being and cognitive functioning, which are all falls risk determinants in their own right in older adults, as are potentially heightened pain levels and analgesic use [41], having a decreased social life and fewer in-person social interactions as a result of the pandemic [42], plus ensuing and unrelenting difficulties in accessing needed or regular health and social services [7,43]. Moreover, addressing depression through the use of antidepressants may independently heighten falls risk in fall prone older adults [1,5,6,44], even after controlling for demographic, functional, and health characteristics, including depression [45-50].

Discussion

One of the most pervasive problematic health issues facing older adults is the fact they are often highly prone

to falls and falls injuries. Accordingly, the prevention of falls among older adults, especially those living in

the community has been one of the most important public health issues in today’s aging society, regardless

of country or locality [30,51]. However, although much research in this regard has been forthcoming,

falls prevention efforts that need to be carried out on a community wide scale remain highly challenging

to implement, given their multiple dimensional nature. As well, even when these prevention efforts are

implemented as designed they may still fail to offset the risk of an older homebound adult incurring a falls

injury, in the face of lockdown restrictions and COVID-19 fears and susceptibility, unless careful thought

is forthcoming [1]. In particular, the multiple emotional as well as physical health issues associated with

COVID-19, potentially render the need for more refined programmatic approaches, especially in light

of recent observations that social isolation alone has the potential to markedly increase falls risk [49,52].

As well, despite the importance of non pharmacologic approaches for averting falls in the home, such

as counseling, appropriate diagnostic opportunities, exercise and environmental modifications [51], their

delivery is likely to be suboptimal at best under pandemic lock down restrictions that commonly include the

closure of gyms and group Tai Chi classes, plus face to face counseling and home improvement assistance.

In addition, in face of the unremitting and unpredictable pandemic itself and its emotional correlates, such

as depression, an independent falls predictor, as well as important health correlate in general, an increase in

falls risk, as well as injury severity, plus COVID-19 vulnerability can be anticipated, especially in the higher

age groups [1,53].

Unsurprisingly, and in accord with Kvelde et al. [54] who conducted an earlier meta analysis of this issue, the current review strongly indicates that more attention to the potentially highly deleterious linkages between stress, fear, anxiety, declines in overall wellbeing, social isolation, and possible falls risk and depression risk or exacerbation, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic as discussed by Norman et al. [55] and Shin et al. [56] is indicated.

This is because, as well as an fostering an endless downward cycle of debility, failure to do so is likely to increase hospital readmission rates [56] at a time when personnel are stressed and beds are limited to serve pandemic cases. Exposure to COVID-19 infections in the hospital is also possible. Hospital personnel may also fail or be unable to address the actual needs of the older adult with a falls injury due to a host of instrumental constraints, thus recommended depressive assessments, and the delivery of carefully tailored and targeted non pharmacologic directives [4,54,57] may be overlooked. Moreover, efforts to check for and administer antidepressant medications only if essential and in a safe manner may be omitted as well [57].

To counter this aforementioned situation, a proactive approach that aligns with best practices and what is currently available or not available is highly recommended in this regard [3,54]. This may entail any necessary counseling intervention, equipment and environmental modifications needed in the home, as well as attention to footwear, and vision needs.

As outlined by Quash et al. [49] it appears especially important in this regard to focus on efforts to combat social isolation, and its correlation with falls, depression, and poor health status. At the same time, rather than waiting for the tide to turn, media and public health advocates are urged to devise simple messages to apprise the public of the importance of protecting older community dwelling adults against falls and depression and how this can be done cost-effectively and independently until programs are reinstated. The possible related dangers of antidepressant drugs and others in fall prone older adults should be highlighted here as well other factors that may also be influential in the context of community home based falls and that are modifiable [51] during the pandemic, where falls injuries occurred more often in the home and were more serious than in pre pandemic times [58]. These include but are not limited to behaviors that impact:

Malnutrition

Obesity

Osteoporosis

Sedentary practices

Stress

Sleep disturbances

By contrast, a failure to provide a clear understanding of the possible linkages between behaviors and falling and between falling, depression, and COVID-19 among older adults, including the role of social isolation in mediating or moderating this association may predictably result in immense excess personal as well as societal costs and increases in hospitalization rates due to excess ground level falls incurred by the elderly during the 2020 pandemic period [59], as well as osteoporotic fractures [11]. However, by starting to simply target older adults and their families and health providers, and especially identifying older adults at high risk for falls, and depression, including those who have suffered from COVID-19 as well those suffering from multiple comorbid health conditions, and contacting them to provide any necessary resources to offset any falls risk, as well depression risk is strongly considered [27].

Individuals living in the community who might benefit most are-

Those who are sedentary with mobility problems [2,17,60]

Those with multiple co-morbid health conditions [17,21,24,60,61]

Previous fallers [17]

Those who live alone/who are socially isolated [3,49]

Adults older than 80 years of age [62,63]

Those who are depressed [17,60]

Those with impaired vision [23,60]

Those with hearing problems [24]

Those who are weak and frail [23]

Those taking diuretics, sedatives, narcotics, psychotropic, antihypertensive drugs [46]

Older men with a falls history [62]

Those with cognitive impairments [21]

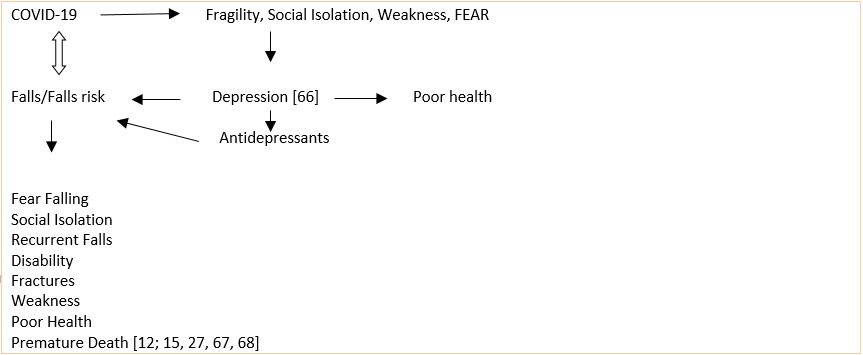

Potential improvements of a well constructed carefully tailored falls prevention program, albeit possibly only able to produce modest benefits [64], include multiple physical, mental, and financial benefits, along with a reduction in fall frequency and severity, as well as possible COVID-19 infection rates, as opposed to preventable decreases in overall well-being, and suffering, plus the likelihood of fragility fractures, and lower survival rates seven years later, beyond the effects of age, gender, marital status, and education [53,65] {See Figure 1}.

In sum, as per Choi et al. [25] as well as Hoffman et al. [37], the nature of the relationships between baseline depression and \subsequent multiple falls point to the importance of incorporating depression screening and treatment, along with medication assessments in fall prevention efforts for older fall prone adults living in the community, where a higher percentage of falls currently occur [69]. In addition, efforts to assess falls awareness among isolated older adults and their families appears indicated, along with periodic health and medication checks, plus any negative illness perceptions and manifestations, including inflammation, and excess fragility [46,67,68,70-72].

Limitations to the above discourse are its focus on the community, older adults, and one major website, and the fact our current falls prevention approaches have tended to only produce modest benefits and the quality of the evidence is low [64], and may not include a broad enough spectrum of adults [65], hence more extensive exploration of this topic, especially the role of behavioral factors [73] and whether early intervention is efficacious or not is highly recommended [74].

Key Conclusions

Falls and their injuries and consequences remain a serious seemingly intractable health problem for older

adults currently living in the community amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

Implementing falls as well as depression and social isolation screening and personalized intervention on a

more systematic basis among those aging adults currently living in the community who appear at high risk

for falling and/or depression could possibly help to minimize falls injuries and risk among older community

dwelling adults, as well as COVID-19 disease due to weakness and frailty.

While much is currently being written about the impact of COVID-19 on mortality rates among older

individuals, the associated of COVID-19 as regards falls injuries as well as depression warrants more intense

scrutiny and attention.

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!