Biography

Interests

Getu Teferi

Department of Sports Science, Debremarkos University, Debremarkos, Ethiopia

*Correspondence to: Dr. Getu Teferi, Department of Sports Science, Debremarkos University, Debremarkos, Ethiopia.

Copyright © 2020 Dr. Getu Teferi. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Health enhancing physical activity (HEPA) is a term used particularly “any form of PA that benefits

health and functional capacity without tiredness”. The purpose of this study is to assess the habits

and educational preparation on physical activity of healthcare professionals.

A cross-sectional survey design was used to assess healthcare professionals’ physical activity habits

and their educational preparation on physical activity in hospital setting. Source populations of the

study were the registered healthcare professionals with any age and sex and currently on practice

in the sample hospitals and the sample size was determined by using the formula for estimating a

single population proportion. Regarding data collection tools: Demographic information and the

key variables of the study were collected through questionnaire.

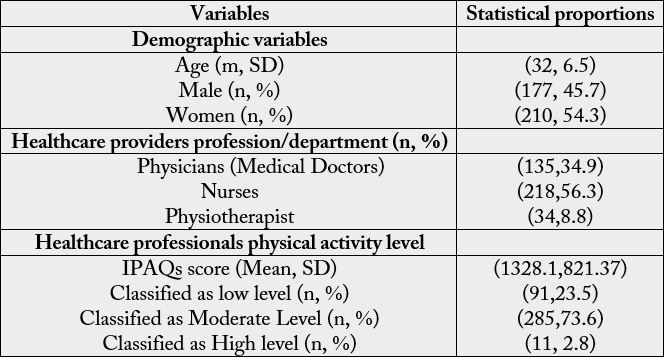

A total of 442 healthcare professionals from 7 government hospitals in Addis Ababa city participated

in the study. From these hospitals 387 healthcare professionals (physicians=135, 34.9%, nurses=218,

56.3% and physiotherapist=34, 8.8%) completed the questionnaire. The majority of (73.7%) of

healthcare professionals categorized moderate level of physical activity, only 2.8% of participants

in the study were suggest that highly physically active and only 23.5% of the respondents were

categorized as low physical activity level.

In general, above the three/fourth of participants were categorized as physically active and nearly

one/third of the respondents categorized as low level of physical activity. There was a significant

difference among healthcare professionals regarding to physical activity level (physicians: Mean

rank =197.56, Nurses: Mean rank =151.64, Physiotherapist: Mean rank =256.65, X2 = 28.537, df

= 2, p = .000). Specifically, physiotherapists were more physically active than physicians and nurses

and nurses were less physically active. Almost all healthcare professionals (N=387) 95.3%) would

be interested in obtaining training related to physical activity prescription/counseling.

Introduction

The terms exercise and physical activity are often used interchangeably. However, exercise is a subcategory of

physical activity and has been defined as “planned, structured, and repetitive and purposive in the sense that

the improvement or maintenance of one or more components of fitness is the objective”, and in some studies

sports participation is assessed and analyzed separately from other leisure‐time activities [1,2]. Physical

activity is sometimes defined synonymously with fitness. The fitness concept includes aerobic capacity,

strength, flexibility, speed and power [3].

Sedentary behavior has during the last years been separated from low physical activity. It is defined as “activities that do not increase energy expenditure significant above the resting level” (1.0-1.5 metabolic equivalent units) and includes activities such as sleeping, sitting and lying down [4]. PA can be categorized in various ways, including type, intensity, and purpose. With regard to classification by “purpose,” physical activity is frequently categorized by the context in which it is performed [2]. According to [2] commonly used physical activity classification include occupational, leisure time or recreational, household, self‐care, and transportation physical activities. Health enhancing physical activity (HEPA) is a term used particularly among the European health promotion community, and is defined as “any form of PA that benefits health and functional capacity without tiredness” [5,6].

The actual physical activity can be measured or assessed by different methods or tools. Three types of physical activity assessment methods are currently available in clinical settings: direct measurement methods using calorimetric (e.g. doubly labeled water), objective methods measuring physical effort (e.g. pedometers and accelerometers) and subjective methods that are dependent on individual recall, including questionnaires and activity diaries. The more sophisticated methods (other than subjective) are more time and labor consuming and thereby costly, and are in many cases considered to have lower feasibility for large‐scale studies. Subjective measurement methods are inexpensive and more easily applicable to large populations. However, subjective methods rely on subjective interpretation of the questions and the perception of physical activity behavior from the participant [7].

The methods of assessing PA can be summarized as self-reported or objective measures. The method to choose depends on whether to measure the PA behavior or the energy expenditure. PA as a behavior can be assessed with direct measures such as observations, PA can also measure with self-reported questionnaires and fitness tests. Self-reported questionnaires have high feasibility and are often used in large populations since the method is inexpensive and easy to administer [8]. Some research findings have found that overestimation of PA occurs and should be taking into consideration when using self-reported questionnaires [5,7].

The most common self-reported questionnaire that in use are the standardized instrument, the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAC) and the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire [9,10]. IPAQ is validated in 12 countries. The questionnaire comes in a short form with 7 items and a long form with 27 items, and shows acceptable measurement properties for measuring the population physical activity level [9]. Self-reported personal physical activity level of healthcare professionals was measured by the validated questionnaire of International Physical Activity Questionnaire short form [11].

In one study on Correlation of primary care physicians’ exercise habits and their age [12] revealed that the exercise habits of primary care physicians were significantly correlated with their age and workplace, but not with their specialty. Their age group was positively associated with their PA habits. Those in the older age group were more likely to do more PA than those in the younger age groups. Healthcare professionals who were normal weight more physically active than the other sub groups. Physicians and medical students with a normal BMI, and who achieved moderate and vigorous USDHHS guidelines, were more likely to feel confident about counseling/prescribing PA to their patients than those who did not achieve the guidelines or those who are overweight or obese [13].

There is evidence from different scientific research for the benefit of exercise in many forms of disease. It is effective, less cost, with a low side effect, and can have a positive environmental impact. Despite this, there remains reluctance within the healthcare professionals to use PA as a treatment. This probably reflects a lack of knowledge or educational preparation among healthcare professionals regarding to physical activity for counseling and prescription purpose [14].

Healthcare professionals have inadequate training in non-pharmacological methods, which means that there is uncertainty about prescribing physical activity. Physical activity prescription is not a priority for healthcare professionals because other tasks are considered more important. The competences of healthcare professionals need to be utilized to achieve optimum teamwork in physical activity prescription/counseling. The healthcare professionals point out that the proper conditions have to be established in society and in the health service to increase the PAL among patients to manage and prevent chronic diseases [15]. There is sometimes a struggle about who should be can prescribe medicines, but when it comes to physical activity prescription/counseling there is opposite situation: it is a task that healthcare professionals would prefer not to perform. They have reservations about using PAP because they give priority to other tasks [15].

Physical activity prescription requires healthcare professionals’ knowledge about physical activity in other way it requires educational preparation how to counsel/prescribe physical activity to their patients. According to [16], since insufficient exercise education in medical school and training were also chosen as important barriers, it is important that medical educators evaluate curricula to see if there are deficiencies in exercise science/counseling. In general, the purpose of this study is to assess the physical activity level and educational preparation of healthcare professionals.

Objectives of the Study

To determine physical activity level of healthcare professionals

To assess the educational preparation of healthcare professionals

Methods and Materials

A cross-sectional survey design was used to assess Addis Ababa’s, healthcare professionals’ physical activity

counseling and prescription behavior for non-communicable diseases in hospital setting. Ethiopia has a total

of 9 regions and two administrative cities. Addis Ababa city is among those and the capital city of Ethiopia.

Addis Ababa city was providing the setting for the study. Source population of the study was the registered

healthcare professionals (medical doctors, nurses and physiotherapist) with any age and sex and currently on

practice in the sample hospitals.

Hospitals have to meet the following criteria to be included in the study: Hospitals that give services related

to: cardiovascular diseases, diabetic type 2, chronic respiratory diseases. Regarding to participants had to meet

the following criteria were included in the study: a registered medical doctors, nurses and physiotherapist,

male or female, currently working in the sample hospitals and age range 26-40.

Hospitals would exclude which, during the study time, have not given services related to cardiovascular diseases, diabetes type 2 and chronic respiratory diseases. Participants who met the following criteria were excluded from the study: healthcare professionals still busy with their community service and If the participants are not voluntary.

The sample size was determined by using the formula for estimating a single population proportion. Sample

size was calculated by taking the proportion of physical activity prescription/counseling which is 50%

on healthcare professionals (medical doctors, nurses and physiotherapist) for chronic disease with 95%

confidence level, 5% margin of error to get an optimum sample size that allowed the study to look into

various aspects of physical activity prescription/ counseling among healthcare professionals. Why have taken

population proportion 50% because there is no previous study in this area, in our country, and impossible to

predict the population proportion on physical activity prescription/ counseling for chronic diseases among

healthcare professionals. Based on the above assumptions, the formula is as follows [17].

s = required sample size

X2 = the table value of chi-square for 1 degree of freedom at the desired confidence level

(3.841)--------------- 1.96 x1.96 =3.8416

N = the population size

P = the population proportion (assumed to be .50 since this would provide the maximum sample size).

d = the degree of accuracy expressed as a proportion (.05).

Based on this formula the maximum sample size would be 384, assume 85% would be return rate, then add

15%, the total sample would be 442.

First, have been contacted Addis Ababa city health bureau to get information and list of government

hospitals. Then based on the information and the inclusion criteria the sample hospitals have been selected.

Second, contacted each sample hospitals’ medical director and get permission, information about number of

population (medical doctors, nurses and physiotherapist) in each hospital. Finally, by using simple random

technique and stratified sampling from the sample hospitals, the following samples have been drowning:

Physicians =175, Nurses = 225 and Physiotherapist = 34, totally 442 healthcare professionals were selected

as sample subjects for this study.

Self-reported personal physical activity level of healthcare professionals would measure by the validated

questionnaire of International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) short form [11]. The purpose of the

questionnaires is to provide common instruments that can be used to obtain internationally comparable

data on health–related physical activity. To assess the participant’s physical activity, level the International

Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) short version survey was used [11]. The IPAQ was constructed to

assess physical activity level among individuals aged 15-69. The full IPAQ measures; leisure time physical

activity, domestic and gardening activities and work related physical activity [11]. The IPAQ short version

assesses three types of physical activity; walking, moderate intensity activities and vigorous intensity activities.

The IPAQ short version was selected because it is a validated survey and provides a validated scoring system.

The IPAQ survey short form has been shown to have acceptable test reliability in prior studies. For instance,

in a 12 country evaluation study [17], it has also been used for a larger scale study like the Euro-parameter

which measured physical activity level among Europeans and a survey that measured physical activity levels

in 51 countries, conducted by the WHO [18]. To categorize the participant’s physical activity levels, the

IPAQ scoring system were used. The data was cleaned according to IPAQ scoring system with the exception

that the participants who had reported frequency and not duration or vice versa was reported as zero instead of missing value which the IPAQ data cleaning suggested. The reason why this modification was made was

to avoid missing values and exclude some answers from the analysis. This modification was done in another

study, when the aim was to measure physical activity level by using the IPAQ [11].

A participant´s physical activity level could be categorized as low, moderate or high. To be categorized as “high” the participant had to achieve vigorous intensity activities of at least 3 days a week, or 7 days or more of any combination of walking and moderate intensity or vigorous intensity activities. To be categorized as “moderate” the participant had to achieve at least 3 days of 20 minutes per day, or 5 or more days of moderate intensity activity involving at least 30 minutes per day [11]. To be categorized as “low” neither of these criteria above were achieved. Prior to entering the categorized data material to SPSS the data was numbered as 1 for low, 2 for moderate and 3 for high. These activity categories were multiplied by their estimated intensity in metabolic equivalents (METs) and summed to gain an overall estimate of PA in a week [11]. One MET represents the energy expended while sitting quietly at rest and is equivalent to 3.5 ml/kg/min of volume of oxygen (VO2). The MET intensities used to score IPAQ in this study were vigorous (8 METs), moderate (4 METs), and walking (3.3 METs).

Low physical activity, no physical activity or some activity reported, but not enough to satisfy the requirements of the other two categories; Moderate PA, any of the following three criteria: (1) 3 or more days of vigorous intensity activity for at least 20min/day, (2) 5 or more days of moderate intensity activity or waking for at least 30min/day, or (3) 5 or more days of any combination of walking, moderate intensity, or vigorous intensity activities achieving a minimum of 600 ME minutes per week; High PA either of the following two criteria: (1) 3 or more days of vigorous intensity activity accumulating at least 1500 MET minutes per week or (2) 7 days of any combination of walking or moderate‑ or vigorous intensity activities achieving a minimum of 3000 MET minutes per week.

The present study was conducted from December to February 2019 and the manuscript was prepared in

September 2020.

Results

A total of 442 healthcare professionals from 7 government hospitals in Addis Ababa city participated in the study. From these hospitals 387 healthcare professionals (physicians=135, 34.9%, nurses= 218, 56.3% and physiotherapist=34, 8.8%) completed the questionnaire. From the international physical activity questionnaire, healthcare professionals’ physical activity level reported that classified as low level (91, 23.5%), moderate level (285, 73.6%), and high level (11, 2.8%). More than half of healthcare professionals (76.4%) were classified as physically active.

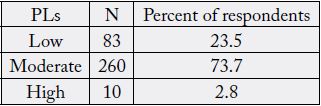

Regarding to physical activity levels of HCPs’ from IPAQ, computed MET-minutes per week then categorized in to three different categories of physical activity levels: Low, Moderate and Vigorous as suggested in “International Physical Activity Questionnaire” (IPAQ, 2004, 2005). Our study revealed that the majority of (73.7%) of healthcare professionals reported moderate level of physical activity, only 2.8% of participants in the study were suggest that highly physically active and only 23.5% of the respondents were categorized as low physical activity level. In general, above the three/fourth of participants were categorized as physically active and nearly one/third of the respondents categorized as low level of physical activity (see on Table 2).

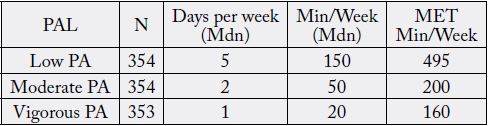

As observed from Table 3 below, the participant healthcare professionals were physically active for a total of 220 minutes per week (Low PA: Mdn =150min/week, Moderate PA: Mdn = 50Min/week and Vigorous PA: Mdn = 20Min/week) by walking and involving in different moderate and vigorous physical activities. The respondents walked (low physical activity level) about 150 minutes per week. And also, the participants involved in moderate level of physical activity, like carrying light loads, bicycling at a regular pace, double tennis and brisk walking for about 50 minutes and they were performed vigorous level of physical activity such as, heavy lifting, digging, aerobics, or fast bicycling for 20 minutes per week. Participant’s weekly physical activities performed were converted to Metabolic Equivalent (MET-Minutes) which considered the intensity of the physical activity performed.

In measured MET- minutes, Vigorous physical activities can contribute more to the total energy expenditure (MET) per week than the moderate and low physical activities. But, the present study suggests that low physical activity (walking) was the most commonly doing physical activity among HCPs, which providing the highest energy expenditure (495 MET-minutes per week).

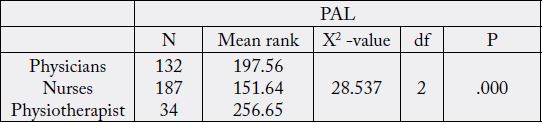

To show the differences among healthcare professionals in relation to physical activity level we apply Kruskal-Wallis test. Therefore, the finding revealed that there was a significant difference among healthcare professionals regarding to physical activity level (physicians: Mean rank =197.56, Nurses: Mean rank =151.64, Physiotherapist: Mean rank =256.65, X2 = 28.537, df = 2, p = .000). Specifically, physiotherapists were more physically active than physicians and nurses and nurses were less physically active (see Table 3).

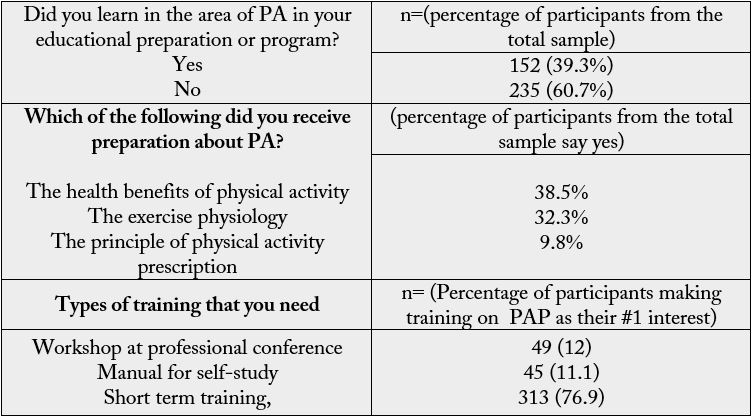

Regarding to educational preparation of healthcare professionals in related to physical activity prescription/ counseling, only 39.3% of participants reported that receiving educational preparation to counsel patients on physical activity during their educational program (see Table 4). Among these healthcare professionals who reported receiving educational preparation about physical activity during their educational programs, the topic of lessons most commonly received were: the health benefits of physical activity (38.5%), exercise physiology (32.3%) and the principle of physical activity prescription (9.8%).

Key note: n = Number of Participants

Almost all healthcare professionals (N=387) (95.3%) would be interested in obtaining training related to physical activity prescription/counseling. Among these healthcare professionals who reported interested in obtaining training related to physical activity prescription/counseling: most of participants were interested through short term training (76.9%), workshop or conference/seminars (12%) and manual for self-study (11.2%).

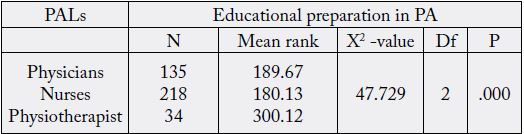

Regarding to healthcare professionals’ educational preparation in the area of physical activity, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test, to show the differences of the three groups (physicians, nurses and physiotherapist). Mean rank differences of Kruskal-Wallis test suggest that there was a significant difference among healthcare professionals in their educational preparation in the area of physical activity (χ2 = 47.729, df = 2, p = .000).

Note: PALs = Healthcare professionals’ physical activity level, X2 -value = chi-square value, df = degree of freedom, P = Significant level at P< .05 a Questions forwarded for healthcare professionals: Did you learn in the area of PA in your educational preparation/program? In Yes or No form

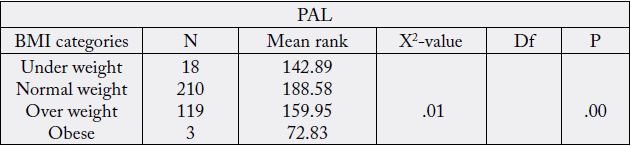

Specifically, among the three groups physiotherapists have thought more about physical activity during their educational program than the other two groups. The mean rank differences have shown that physiotherapist more thought than others (M = 189.67) physicians (M= 180.13) and nurses (M = 300.12). Differences of the respondents’ physical activity level among their body mass index sub group, to show this differences, the Kruskal-wallis test was applied. Therefore, the present study result reported that there was a significant difference among healthcare professionals’ physical activity level in reference with their body max index sub groups (under weight: Mean rank =142.89, Normal weight: Mean rank =188.58, Over weight: Mean rank =159.95, Obese: mean rank = 72.83, X2 = 11.28, df = 3, p = .01). Generally, Healthcare professionals who were normal weight more physically active than the other sub groups and the second more physically active next to HCPs who were with normal weight was over weight (see Table 4.29).

Key note: BMI = body mass index, PAL = physical activity level

Discussion

The present study suggests that more than half (73.7%) of healthcare professionals doing moderate level

of physical activity, only 2.8% of participants were revealed that highly physically active and 23.5% of the

respondents were categorized as low physical activity level. In general, above the three/fourth of participants

were categorized as physically active and nearly one/fourth of the respondents categorized as low level of

physical activity. In line with this [19] suggest that 44.32% of healthcare professionals were doing moderate

physical activity, 25.35% were participating in mild exercise and 20.88% were doing high physical activity.

Small proportions of physicians (9.45%) were not doing any exercise or rarely doing any physical activity.

Moderate to high physical activities totally constitute 65.2% of the total number of physicians. In South India

one study conducted on “Doctors’ self-reported physical activity and their counseling practices” demonstrate

that moderate PA was reported by 37.7% of the doctors and the remaining 62.3% reported being inactive.

Most of participants were physically inactive [19]. In other study more than half of physicians (64%) were

classified as physically active [19,21]. Reported that 42% were physically active. In general, the present study

has shown that most of the participants’ physical activity level was categorized as moderate level. Regarding

to the difference between male and female physicians in their physical activity level, Chi-Square test did

not show any significant difference (P>0.05, χ2=0.44, OR=1.48, CI=0.47-4.63) in physical activity between

males and females [19]. In line with this the present study revealed that there was not a significant difference

between male and female healthcare professionals’ physical activity level (X2 = 1, df = 2, p = .590 or p > 0.05).

In one study on Association of primary care physicians’ PA habits and their age [12] reported that the PA habits of primary care physicians were significantly correlated with their age and workplace, but not with their specialty. Their age group was positively associated with their exercise habits. Those in the older age group were likely to do more exercise than those in the younger age groups. In line with this, the present study has shown that there was not a significant association between healthcare professionals’ physical activity level and their age (X2 = 4.363, df = 3, p = .225 or p > 0.05).

Differences of the respondents’ physical activity level among their body mass index sub group, to show this differences Kruskal-wallis test was applied. Therefore, the present study has reported that there was a significant difference among healthcare professionals’ physical activity level in reference with their body max index sub groups (under weight: Mean rank =142.89, Normal weight: Mean rank =188.58, Over weight: Mean rank =159.95, Obese: mean rank = 72.83, X2 = 11.28, df = 3, p = .01). In relation to this, generally healthcare professionals who with normal weight were more physically active than the other sub groups and the second more physically active was who with overweight. Physicians and medical students with a normal body mass index, and who achieve moderate and vigorous USDHHS guidelines, were more likely to feel confident about counseling/prescribing PA to their patients than those who did not achieve the guidelines or those who are overweight or obese [13]. The present finding revealed that there was a significant difference among healthcare professionals regarding to physical activity level. Specifically, physiotherapist was more physically active than physicians and nurses. One study conducted on Physical activity among Saudi Board residents in Aseer region, Saudi Arabia [21], showed that more than 47% of participant physicians were physically inactive and more than 31% were moderately inactive [22].

Conclusion

This is the first study assessing the self-reported PA habits and educational preparation among healthcare

professionals in Ethiopia. In relation to healthcare professionals’ physical activity level, the present study has

suggested that most of healthcare professionals categorized as moderate level of physical activity. The present

study shows that, there was not a significant difference between male and female healthcare professionals’

in their physical activity level and there was not a significant association between healthcare professionals’

physical activity level and their age. Specifically, physiotherapists had greater physical activity level followed

by physicians (medical doctors). In other way nurse’s physical activity level were also low. Most of the

participants reported that, they have not thought about physical activity in their educational preparation to

counsel patients on physical activity during their educational program. Almost all healthcare professionals

would be interested in obtaining training related to physical activity prescription/counseling through short

term training.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank you for Sample Hospitals’ Medical Directors for their permission conduct this paper,

Addis Ababa Health Bureau, St. Paulos Specialized Hospital, and St. Peter TV specialized Hospital for

facilitating and giving Ethical Clearance and for all participants of healthcare professionals.

Conflict of Interest

I do know of no conflicts of interest related to this publication, and there has been no significant support for this work that would have influenced its outcome. As Corresponding Author, I confirm that the manuscript

has been read and approved for submission.

Funding Agency

Debremarkos University

Data and materials availability statement should be mentioned.

Ethical Clearance

Ethical Clearance for the present study was obtained from Addis Abeba City administrative health bureau,

St. Paulos Specialized Hospital, and St. Peter TV Specialized Hospital.

Statement of Written & Oral Informed Consent

Written & oral informed consent were obtained from all individual participants in the present study.

Data and Materials Availability

The data and materials are available.

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!