Biography

Interests

Dalal Naeem M. I.1, Siulapwa Ntungo, J.2 & Ravi Paul3*

1MBCHB, BSCHB, MMED Psychiatry and Mental health Registrar, Department of Psychiatry, School of

Medicine, University Teaching Hospitals Adult Clinic 6, Lusaka, Zambia

2MBCHB, BSCHB, School of Medicine, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia

3MBBS Neuropsychiatry Consultant, Head, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University Teaching

Hospitals Adult Clinic 6, Lusaka, Zambia

*Correspondence to: Dr. Ravi Paul, MBBS Neuropsychiatry Consultant, Head, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, University Teaching Hospitals Adult Clinic 6, Lusaka, Zambia.

Copyright © 2019 Dr. Ravi Paul, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Graduating as a medical doctor takes an average of 7 years after which another 7 years are invested

to be conferred with a consultancy in Zambia. Coupling the many number of years of education to

high patient- low doctor ratio, medical doctors are at high risk of occupational health. “Burn Out

Syndrome (BOS) is a work related constellation of symptoms that usually occurs in individuals

without any prior history of psychological or psychiatric disorders. Medical doctors are at high risk

of occupational health leading to BOS. BOS is triggered by a discrepancy between the expectations

and ideals of the employee and the actual requirements of their position. In the initial stages of

BOS, individuals feel emotional stress and increasing job related disillusionment. Subsequently they lose the ability to adapt to work environment and display negative attitudes toward their

job, co-workers, and their patients. Ultimately, three classic BOS symptoms develop: exhaustion,

depersonalisation, and reduced personal accomplishment [1].” Little is known about the prevalence

of BOS among Zambian health care service providers and medical doctors in particular. This study

explores the factors associated with BOS, its prevalence at the University Teaching Hospital’s

(UTH’s) in Lusaka, Zambia and its implications. The study also highlights measures to put in place

in order to curb BOS and promote wellbeing among health care providers.

A three 3 part self-administered questionnaire that contained a Maslach Burnout inventory (MBI)

was distributed amongst doctors in the various hospitals at UTHs to collect data for a sample size

of 126 participants in duration of 4 months from September 2018 to January 2019.

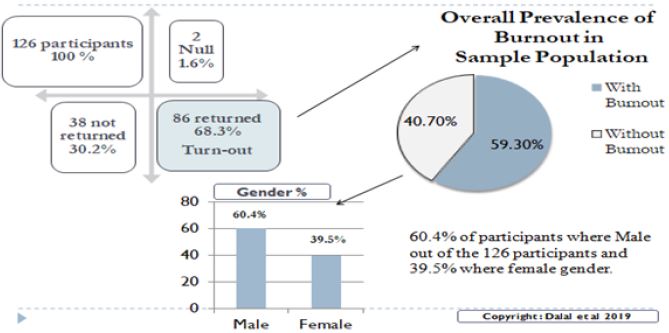

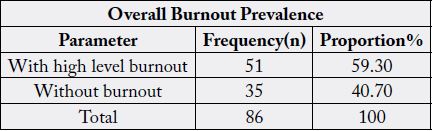

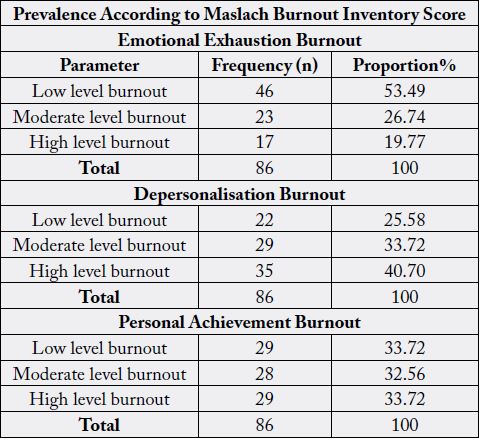

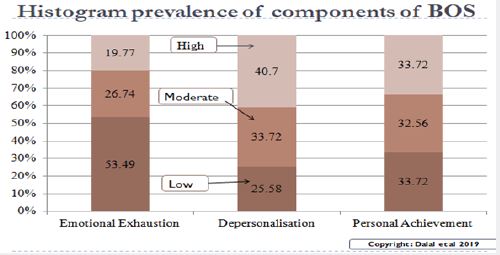

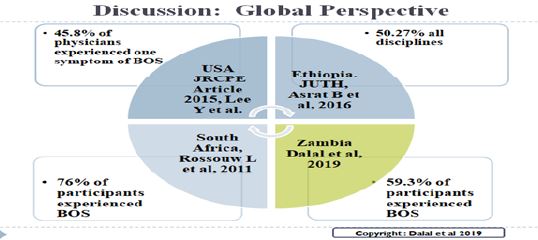

The overall prevalence of burnout at UTHs was found to be 59.30%. With clinically significant

Emotional Exhaustion having a prevalence of 19.77%, Depersonalisation has a prevalence of

40.70% and reduced personal achievement having a prevalence of 33.72%.

BOS and work related stress are significantly prevalent at the UTHs and the statistics shown

highlight the need to safeguard medical doctors mental health by putting up confidential,

professional and easy to access mental health care in the work place to help curb burnout amongst

medical doctors at UTHs and in the Zambian health sector as a whole.

Introduction

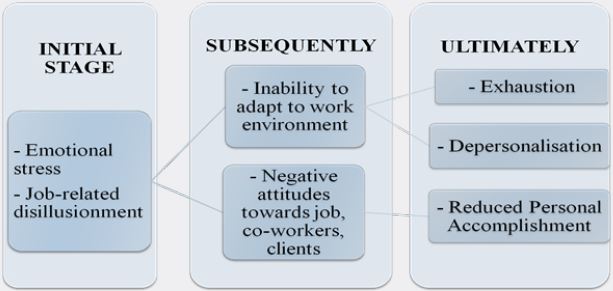

“First described in the 1970s, Burnout Syndrome (BOS) is a work related constellation of symptoms that

usually occurs in individuals without any prior history of psychological or psychiatric disorders. BOS is

triggered by discrepancy between the expectations and ideals of the employee and the actual requirements

of their position. In the initial stages of BOS, individuals feel emotional stress and increasing job-related

disillusionment. Subsequently, they lose the ability to adapt to the work environment and display negative

attitudes toward their job, their co-workers, and their patients. Ultimately, three classic BOS symptoms

develop: exhaustion, depersonalisation, and reduced personal accomplishment [1].”

“Exhaustion (Emotional Exhaustion): is generalised fatigue that can be related to devoting excessive time and effort to a task or project that is not perceived as beneficial [1].” “Within the human services, the emotional demands of the work can exhaust a service provider’s capacity to be involved with and responsive to the needs of service recipients [2].”

“Depersonalisation is an attempt to put distance between oneself and service recipients by actively ignoring the qualities that make them unique and engaging people [2].” “Depersonalisation manifests as negative, callous and cynical behaviours; or interacting with colleagues or patients in an impersonal manner. Depersonalization may be expressed as unprofessional comments directed towards co-workers, blaming patients for their medical problems, or the inability to express empathy or grief when a patient dies [1]”

“Reduced Personal Accomplishment is the tendency to negatively evaluate the worth of one’s work, feeling insufficient in regard to the ability to perform one’s job, and generalised poor professional self-esteem [1]”.

“The scale that has had the strongest psychometric properties and continues to be used widely by researchers

is the Maslach Burnout inventory developed by Maslach and Jackson in 1981 [2]”.

“Burnout is found to be higher in people who are not involved in decision making. Lack of support from

supervisors and colleagues in the work place has also been implicated as one occupational of the causes of

burnout. People who lack a social support system are more likely to develop burnout [2]”.

“Personality traits that present as a possible risk factors for burnout are those of idealism, perfectionism and a great sense of responsibility [3].” A South African study on health professionals working in Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality Community Healthcare Clinic and District Hospital of the Provincial identified long working hours, workload, work conditions and system related frustrations as the most important contributing factors of burnout syndrome ( Rossouw L et al., 2013).

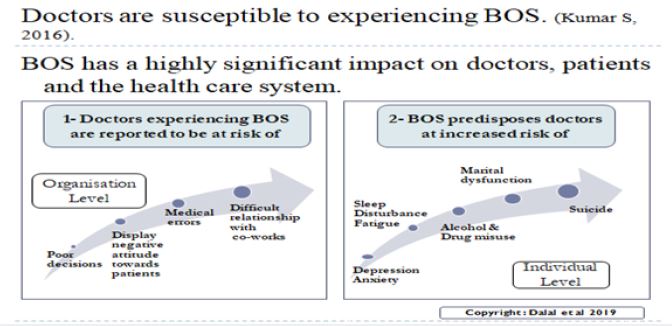

“Doctors are exposed to high levels of stress in the course in their profession and are particularly susceptible

to experiencing burnout. Burnout has a highly significant impact on doctors, patients and the health care

system. Doctors experiencing burnout are reported to be at risk of making poor decision; display hostile

attitude toward patients; make more medical errors; and have difficult relationships with co-workers.

Burnout among doctors also increases the risk of depression; anxiety ; sleep disturbance; fatigue; alcohol and

drug misuse; marital dysfunction; premature retirement and perhaps more seriously suicide [4].”

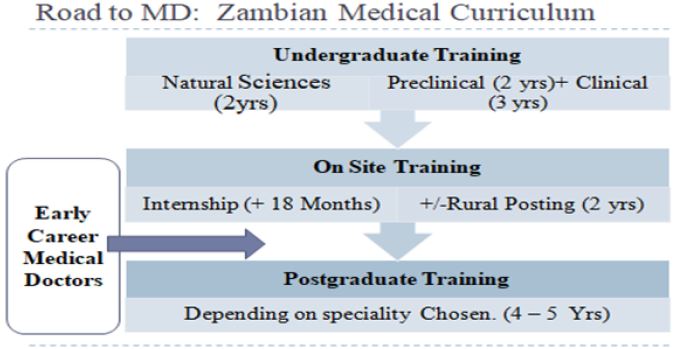

Becoming a doctor is a long and challenging process. In Zambia, upon completion of 5 years of medical

school of training at the University of Zambia (UNZA) with a pre-requisite 2 year course of Natural

Sciences. Graduate doctors are referred to as junior resident medical officers (JRMO) who undergo a

mandatory internship for a minimum duration of approximately 18 months in the four major disciplines

of; surgery, internal medicine, pediatrics and obstetrics and gynecology. Upon completion of internship,

JRMOs are promoted to senior resident medical officers (SRMOs) upon conferment of a full practicing medical license. Being promoted to the rank of SRMO they undergo 24 months of rural posting after which

they can begin their postgraduate studies in a specialty of their choice. The post graduate programs in the

clinical specialties usually run for 4-5 year provided they are no delays and culminate in the promotion to

the rank of senior registrar upon completion of postgraduate studies. After further sub-specialization and/or

years of experience gained a doctor may be conferred the honorary title of Consultant. The Zambian MOH

has also introduced the Specialist Training Program (STP) in 2018 for the training of the specialist doctors

post internship. In this study, early career medical doctors are defined as graduate doctors after starting their

internship until they complete their MMED program.

Located in Ridgeway, Lusaka, UTHs is composed of 5 sub-hospitals being; Children’s hospital, Mother and New Born hospital, Eye Hospital, Adult hospital and the Cancer Diseases hospital. Being the foremost tertiary referral hospital in the country, it used as a training ground for professionals in various health disciplines and incurs a high patient load.

Research Question and Objectives

What is the prevalence of Burn Out Syndrome in early career medical doctors at the University Teaching

Hospitals, Lusaka, Zambia?

To establish the prevalence of burnout syndrome among early career medical doctors at the University

Teaching Hospitals using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)

1) To determine the prevalence of Burnout in early career medical doctors at the University Teaching

Hospital.

2) To determine the factors causing Burnout in early career doctors at the University Teaching Hospitals.

Research Methodology

The study design was quantitative. This method best suited this study because it helped ascertain the

prevalence of BOS among early career medical doctors at UTHs which has been represented as proportions

and it also helped establish causative factors of work related stress with responses participants gave to the

closed ended questions, these responses were then tallied to obtain proportions,. The results obtained were

used to make associations between the causative factors of work related stress and the prevalence of Burnout

syndrome.

Variables used to collect data were demographics, employment information, Maslach burnout inventory

scores, personal, organisational and patient factors causing work related stress, effect of work related stress

on work performance, effect of work related stress emotionally and socially, and ways in which participants

coped with work related stress.

The study was undertaken at the University Teaching Hospital’s Ridgeway Lusaka, Zambia from July 2018

to January 2019.. The questionnaires were distributed to participants in clinics, postgraduate rooms and

hospital wards.

The study population consisted of both male and female medical doctors working in all sub-hospitals at

the rank of junior resident medical officer, senior resident medical officer, and 1st to 5th year Masters of

Medicine (MMED) post-graduate students who were estimated to be 229 in number (as of march 2018)

For the purpose of this study, Early career medical doctors are referred to the above cohort.

The participants had to be full-time employees at UTHs, have been employed for not less than a year, must

be resident doctors from rank of JRMO to final year MMED students.

Doctors not on any form of payroll for the services they provide at UTH.

Sample size Determination The study enrolled a total of 126 participants.

Sample size was calculated in view of determining the prevalence or proportion of burnout amongst the study population.

Where;

S = sample size

Z = Z score

p = prevalence or proportion

M = margin of error

Assuming prevalence of 76% [5], a margin of error of +5% or -5% a 95% confidence interval and Z score for 95% confidence interval being 1.96 . With population being 229.

S =Z2p (1-p)/M2 (Cochran G, 1977)

S= 1.962*0.76(1-0.76)/ 0.052

S = 280.2831

280.2831 is the sample size for an infinity population.

To adjust for the target population:

Adjusted sample size = S / [1 + ((S-1)/population)] (Cochran. G, 1977)

Adjusted sample size = 280.2831/ [1 + ((280.2831-1)/ 229)]

Adjusted sample size = 126.2777 rounded off to 126.

Convenience sampling was used to select participants for the study. The UTHs was stratified into its various

hospitals and, faculty members available and met the inclusion criteria, were chosen to assist in the study by

providing questionnaire evaluation.

All data was collected using interviewer-administered questionnaires. The questionnaires that were used

were designed using closed end questions, in 3 sections. Section A consisted of questions pertaining to

demographics and employment information, section B had an MBI in which questions are answered on a

6 point Likert scale and, section C had questions pertaining to causes of work related stress, effects of work

related stress on work performance, patient care, participants emotions and social life. Questionnaires were

distributed in board-meetings, post-graduate rooms, clinics, wards, on the grounds of UTHs and collected

immediately afterwards, the following day and in some cases the following week. This took approximately

3 and half months, from September to end of December 2018. A brief questionnaire (not more than 10

minutes duration) was used to access BOS. The questions were self-administrative structured for friendly

use. All data was collected in English language.

The information collected on the variables in consideration was entered onto an excel spreadsheet.

Data was imported from the excel spreadsheet and analysed in STATA version 14 software program. In STATA categorical variables were summarised as proportions. Continuous variables were summarized using the mean, median and variance. The presence of clinically significant burnout will be tabulated against demographic variables, employment variables, department of practice, and, possible work related stressors. In order to determine associations with categorical variables the chi squared test and fisher’s exact test were used, with p<0.05 being used to make an inference of a statistically significant association.

On the part of the participants not all medical doctors where available to take part in the study. In cases

where the participants do not meet the criteria, are on leave or do not wish to consent to taking part in the

survey hence resulting in a reduction in sample size ultimately reducing the confidence interval of results.

On the part of the study using a closed ended questionnaire doesn’t give the respondent the opportunity to give their opinions on the questions asked.

Participants were informed about the purpose of the study via information sheets and explanation from

the researcher. Thereafter, they were asked to give voluntary written consent to take part in the study. The

participants were free to seek clarifications and if at any point they felt like withdrawing from the study, they

were free to withdraw from the study without penalty. The risks and benefits of the study were explained to

the participants. Study participants were identified by serial numbers to maintain confidentiality. The data

obtained will not have an impact to employment or education. The Survey results were treated confidentially

with no personally identifying information exposed. Participants who scored high on the MBI survey where

linked with mental health services at UTH Clinic 6 for their well-being.

Permission to conduct the study was sought from management at the University Teaching Hospitals. Ethical approval to conduct the study was sought from the University Of Zambia School Of Medicine Undergraduate Research Ethics Committee. Permission was also sought from the University of Zambia School Of Medicine (UNZASoM) after explaining the purpose of the research.

Results

Of the sample size of 126 questionnaires distributed, 38 were not returned and 2 were discarded due to their

meeting the exclusion criteria. Leaving 86 questionnaires which were used for data analysis (68.3% turnout).

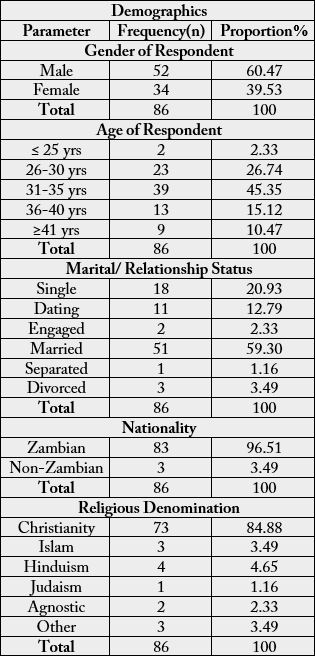

Of the 86 participants 60.47% were male and 39.53% were female. 45.35% of the respondents were between

the ages of 31-35 years, 26.74% were between the ages of 26-30 years, 15.12% were between the ages of

36-40 years, 10.47% were aged 41 or above and 2.33% were aged 25years or below. As is presented in table

1.0 below.

59.30% of the participants were married, 20.93% were single, 12.79% were dating, 2.33% were engaged, 3.49% were divorced and 1.16% were separated from their spouses. This has been shown in table 1.0 below.

96.51% of the participants were Zambian, while 3.49% were non-Zambian. 84.93% of the participants were Christian by religion, 4.65 were Hindu, 3.49% practiced Islam, 2.33% were agnostic, 3.49% belonged to the other category (African tradition, universality etc.) and 1.16% practiced Judaism, as shown in table 1.0 below.

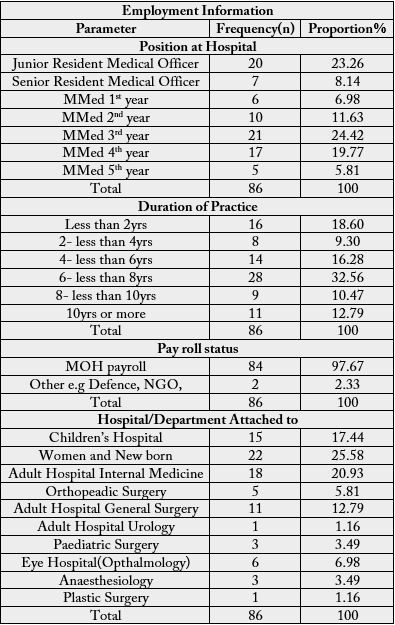

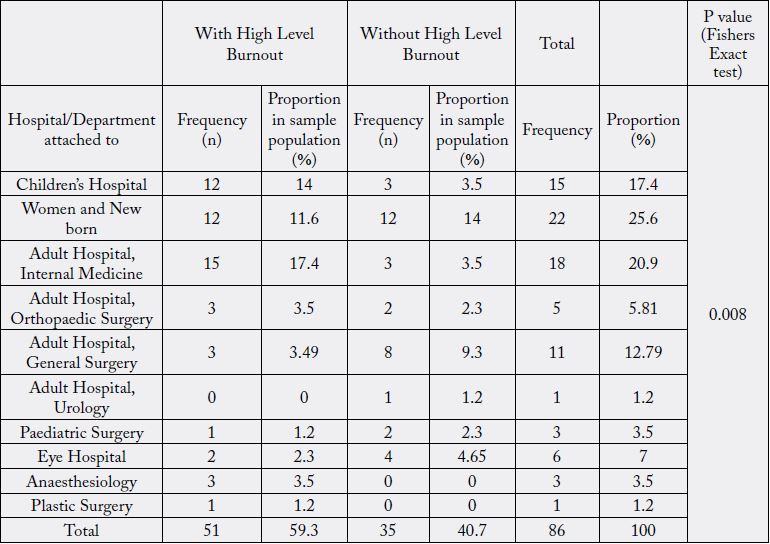

25.58% of the participants came from Women and New born hospital, 17.44% from Children’s hospital,

20.93% from Adult medicine, 12.79% from General surgery, 6.98% from Eye hospital, 5.81% from

Orthopaedic surgery, 3.49% from Anaesthesiology, 3.49% from Paediatric surgery, 1.16% from Urology

and 1.16 from Plastic surgery, as is show in table 2.0.

24.42% of the participants were 3rd year MMEDs, 19.77% were 4th year MMEDs, 23.26% were JRMOs, 11.63% were 2nd year MMEDs, 6.98% were 1st year MMEDs, 8.14% were SRMOs and 5.81% were 5th year MMEDs. 97.67% of the participants are on MOH-payroll and 2.33% are on other forms of payroll (Defence, NGO etc). This has been shown in table 2.0 below.

Discussion of Research Findings

Symptoms of burn out are prevalent at the UTHs and the findings highlight the need to safeguard medical

doctors mental health by putting up confidential, professional and easy to access psychological care in the

work place. This study had a specific objective of defining the prevalence of Burnout among early career

medical doctors at UTHs. The overall prevalence of clinically significant burnout was found to be 59.30%,

this was based on the presence of high level burnout on either the emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation

or personal achievement scales in the MBI.

BOS is a work-related constellation of symptoms that usually occurs in individuals without any prior history of psychological or psychiatric disorders. It is triggered by a discrepancy between the expectations and ideals of the employee and the actual requirements of their position. In 2017, the world mental health day theme was commemorated with the theme of “Mental health in the work place”, this study sheds light on individual and organisational factors that contribute in the development of mental health conditions which may lead to reduced professional efficacy among resident doctors at the UTHs.

BOS is prevalent in health care providers all over the world. With BOS being a constellation of various factors, it is clear that prevalence may vary depending on: career stage, speciality, hospital setting and also part of the world the doctor may be practicing from. Furthermore the levels of burnout in each dimension being; emotional exhaustion, lack of personal accomplishment and depersonalization also varies.

Of the participants with burnout, 59.30% of the sample population, 14% were from the children’s hospital (representing an 80% prevalence in that population), 17.4% from Adult Medicine (representing an 83.3% prevalence in that population), 11.6% from women and new born hospital (representing54.5% of that population), 3.5% from General surgery( representing 27.3% of that population), 3.5% from Orthopaedic surgery (representing 60% of that population), 3.5% from Anaesthesiology (representing 100% of the 2.3% from Eye hospital ( representing 28.6% of that population), 1.2% from paediatric surgery ( representing 33.3% of that population) and 1.2% from plastic surgery ( representing a 100% prevalence in that population. This association is shown in table 5.0 and was made with a p of 0.008, showing a statistically significant association between the prevalence of burnout and the hospital/department the participant was attached to. With burnout being most prevalent in the doctors in Children’s hospital and Adult medicine. A conclusion on the prevalence of burnout within plastic surgery and paediatric surgery, cannot be made due to the very low number of participants that came from these departments.

This study highlighted risk factors that predispose early-career medical doctors to Burnout. On the emotional

exhaustion component; 53.49% of the participants had low level burnout, 26.74% had moderate level

burnout and 19.77% had high level burnout. This showed that 19.77% of the participants felt significantly

emotionally drained, broken down and frustrated by their work. When asked how the work related stress had

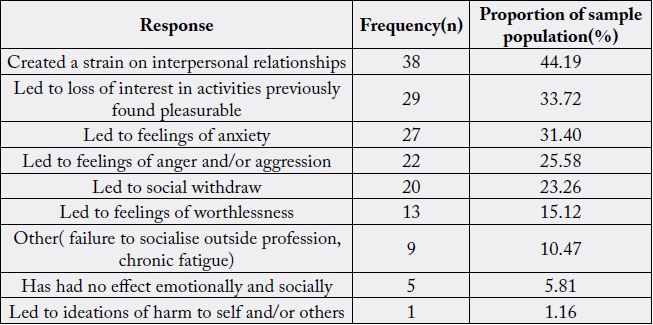

affected them emotionally and socially, 44.19% of the participants said it had created a strain of interpersonal

relationships, 33.72% had lost interest in activities they previously found pleasurable, 31.40% experienced

feelings of anxiety, 25.58% had developed feelings of anger and aggression, 23.26% said it had led to social

withdraw, 15.12% had feelings of worthlessness, 1.16% admitted to it causing ideations of harm to self and/

or others and finally 10.47% said it had led to other effects, such as, chronic fatigue, failure to socialize with

people outside their profession and their being unable to attend social events.

The depersonalisation component showed that 25.58% of the participants had low level burnout, 33.72%

had moderate level burnout and 40.70% of the participants had high level burnout in this component.

Showing that 40.7% of the participants significantly did not care what happens to their patients, had become

insensitive to people and did not look forward to coming to work when they got up in the morning. This is

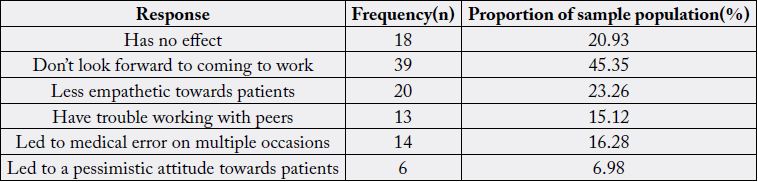

also seen when participants were asked how work related stress affected their work performance and patient

care; 45.35% of the participants admitted to not looking forward to coming to work, 23.26% said they had

become less empathetic towards patients, 15.12% had trouble working with their peers, 16.28% said it had

led to medical error on multiple occasions and 6.98% had developed a pessimistic attitude towards patients.

This symptom if persistent can lead to medical errors at work.

In the lines of personal achievement burnout; 33.72% of the respondents had low level burnout, 32.56%

had moderate level burnout and 33.72% had high level burnout. This goes to show that 33.72% of the

participants significantly felt they did not accomplish worthwhile things at their jobs and felt they did

not effectively look after their patients. Intrinsic motivation is a key factor for overall productivity and

better job satisfaction. Low personal achievement equates to low intrinsic motivation which feeds into

depersonalisation and emotional exhaustion.

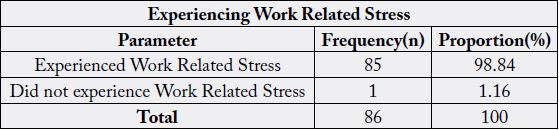

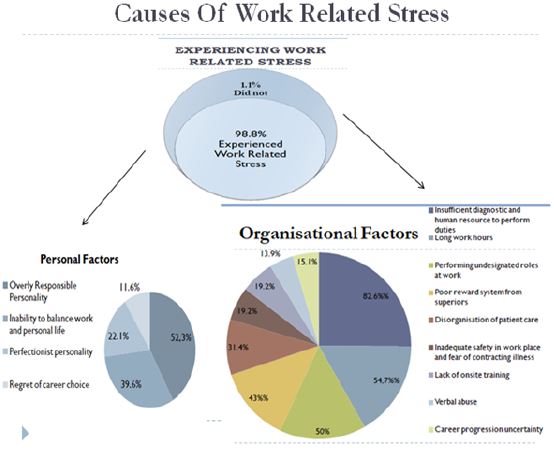

The reason for level of burn out is multifactorial which are divided into Personal, Individual and Patient factors. 98.84% of the participants admitted to experiencing work stress that had plethora of causes that were grouped into personal, organisational and patient factors.

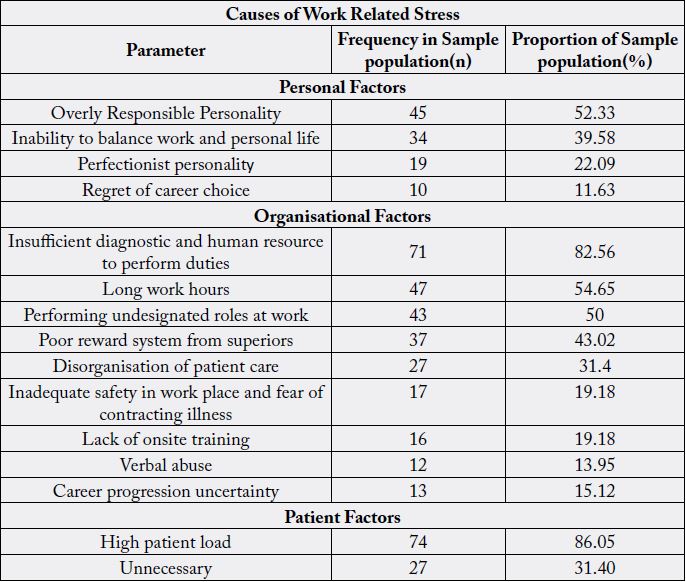

Among the personal factors that were brought out as causes of work related stress; overly responsible personality was seen in 52.33% of the participants, 39.58% of the participants highlighted inability to balance work and personal life, 22.09% their perfectionist personality was a contributing factor and 11.63% listed their regret of career choice as a cause.

The major organisational factor brought out as a cause of work related stress, was insufficient therapeutic, diagnostic and human resource to perform duties, which was mentioned by 82.56% of the participants. Second on the list, was long unstructured working hours as mentioned by 54.65% of the participants. 50% highlighted performing undesignated roles at work such as becoming a clerk, porter or social-worker for optimal patient care. Other organisational causes mentioned were; poor reward system from superiors in 43.02%, disorganisation of patient care in 31.4%, inadequate safety and fear of contracting illness in the work place in 19.16, lack of onsite training in 19.18%, verbal abuse from superiors or patients in 13.95% and career progression uncertainty in 15.12% of the participants.

Patient factors causing work related stress centred on a high patient load which was highlighted by 86.05% of the participants and unnecessary poor patient outcome which was brought out in 31.4% of the participants.

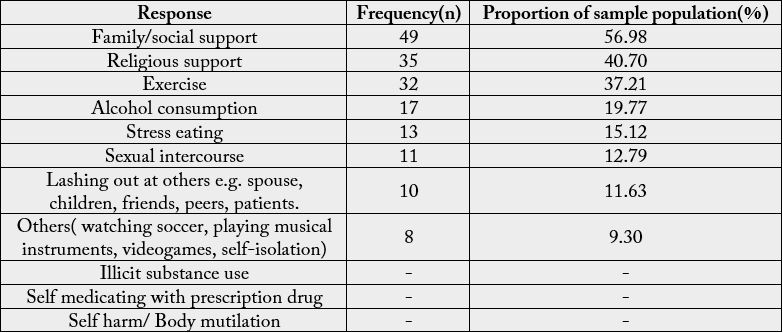

When participants were asked how they coped with the work related stress, 56.98% said they used family/ social support, 40.70% coped using religious support, 37.21% said exercise, 19.77% said alcohol consumption , 15.12% said stress eating, 12.79% said sexual intercourse, 11.63% said lashing out at their family, spouse, children, peers and their patients. 9.3% of the participants sited other means such as watching soccer, playing musical instruments, playing videogame and self-seclusion which is defined as withdrawal from society to recuperate. None of the participants admitted to illicit substance use, self medicating with prescription drugs or self harm/ body mutilation as coping mechanisms. It is also unfortunate that non of the participants had ever sought professional psychological to help cope with the effects of work related stress.

The greatest limitation was the low turnout of questionnaires as a result of; time constraints, damage and loss

of questionnaires, and participants not returning the questionnaires in due time.

Not all targeted medical doctors where available to take part in the study.

A close-ended questionnaire did not give the respondent the opportunity to give their opinions on the questions asked [6-10].

Conclusion and Recomendations

Burnout and work related stress are significantly prevalent at the UTHs and the statistics shown highlight

the need to safeguard medical doctors mental health by putting up confidential, professional and easy to

access psychological care in the work place to help curb burnout amongst physicians at UTHs and in the

Zambian health sector as a whole. There is need for having continued Psychological care for medical doctors

and self-care awareness which will help individuals reach out for support when needed to avoid BOS. The

reason for the level of burn out is multifactorial and a further study is warranted to provide further insight.

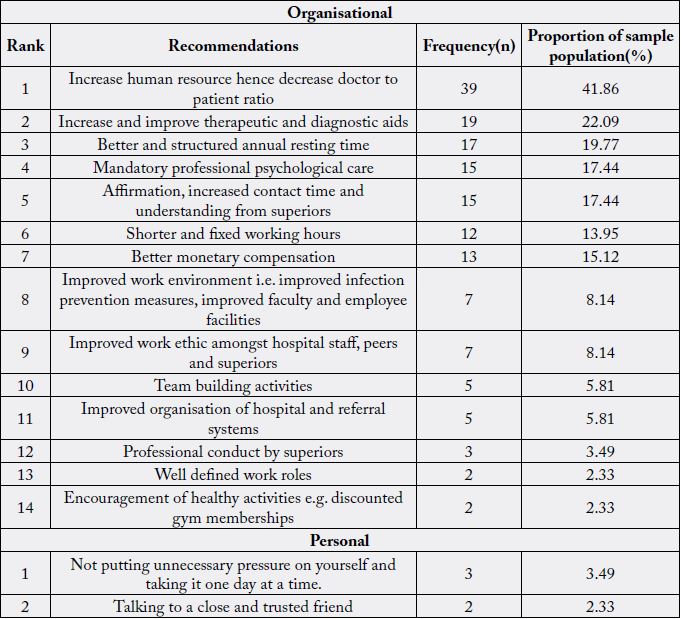

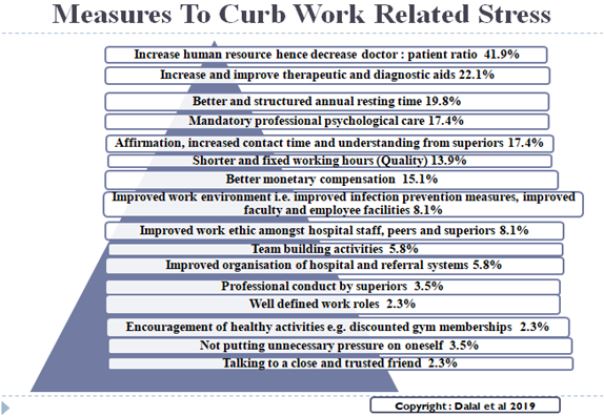

The participants being the most affected by work related stress made recommendations on how to reduce burnout and work related stress. These recommendations are summarised in table 11.

Top of the list was the need for increase in the amount of human resource at all levels hence the reduction in patient load. This will also give the doctors an opportunity to rest and focus on their academic requirements when needed in the case of MMED students.

Improved therapeutics and diagnostic resource will ease the stress of poor patient outcome and limitations to the care a doctor can provide for their patients.

Better and structured resting time, ‘leave days’. Doctors need to get ample resting time from their work without fear of resentment from colleagues who now incur the increase work load created by the absence of one.

Professional confidential psychological care is pivotal to maintaining the mental health of the physician. “We need someone to talk to when we lose patients”, one participant wrote. In relation to this mental health sensitisation initiatives in the work place will also help doctors recognise when they have a problem and need to seek help.

Team building activities were also recommended to help not only improve individual work ethic but also help doctors work well with their peers to improve patient care.

Structured and feasible work hours would go a long way in helping curb chronic fatigue, gain better work of balance giving doctors the time they need with their families and to engage in other coping activities.

Better monetary compensation. Compensation for overtime hours worked and validation of those who go an extra mile in their work will show physicians that they are valued.

Other organisational changes recommended were; well defined work roles, improved work ethic at all levels. Better organisation of patient care, hospital administrative and referral systems.

The organisation should also encourage healthy activities among doctors in ways such as discounted gym memberships.

An overall structure of care for the carer would help medical doctors gain access to mental help services.

Incorporate self-help copping structures in place for medical doctors to understand their own mental health.

Carry out annual studies to evaluate the psychological health of physicians at UTHs and see whether the recommended changes if put in place are contributing to the reduction of BOS in doctors at UTHs.

Multicentre studies should be done at tertiary and primary care level to have nationwide statistics and come up with measures that would improve the psychological health of doctors in Zambia as a whole.

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!