Biography

Interests

Eva Velikoshi-Indongo1, Andros Theu1 & Ravi Paul2*

1Cavendish University, School of Medicine, Zambia

2University of Zambia, School of Medicine, Zambia

*Correspondence to: Dr. Ravi Paul, University of Zambia, School of Medicine, Zambia.

Copyright © 2019 Dr. Ravi Paul, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Mental illnesses have become a global burden. Almost every family is affected by mental illnesses,

either directly as individuals, or indirectly in the manner that the family has to live with and care for

relatives who are suffering from a mental illness particularly where disability has resulted from such

mental illness. In addition to disability, mental disorders tend to be chronic, rendering an individual

partially or completely dependent on his/her family. However, caring for a family member with

a mental disorder places an enormous burden on family caregivers socially, psychologically and

economically. Despite the growing numbers of mental illness that directly resulted in the increase

in population of families living with mentally ill patients, there has been no recent studies focusing

on the experiences of families caring for persons with mental illnesses in Zambia.

The aim of the study was to describe the experiences of the families who are caring for persons

diagnosed with mental illnesses being followed up at the University Teaching Hospital Psychiatric

Clinic and develop health interventions to support these families.

Psychiatric clinic of University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia.

The research was undertaken as a qualitative, descriptive, using a phenomenological approach and

the population consisted of families of patients who are being followed up in Psychiatric Clinic

of UTH. Six families comprised of eight (8) caregivers were studied. In-depth interviews were

conducted using open ended questions and using the developed data collection tool (Annexure I).

Data was analysed using Qualitative Data Analysis (QDA) Miner Lite (Version 5.0 of 2016).

It was revealed that family caregivers experience caring for a mentally ill patient as a difficult, hectic

and challenging task which requires tolerance. As mentally ill persons depend largely on caregivers,

caregivers play an important role in the lives of their patients whereby they have a responsibility to

assist in the performance of daily basic activities and meeting the patients’ basic needs. In provision

of care, caregivers experience social, psychological and economic challenges, for which they use

various coping mechanisms to deal with such challenges. It was also revealed that they require

financial and social care for their patients. Hence, families caring for mentally ill relatives need

social, psychological and financial support in order to provide care to their relatives effectively and

without comprising their own health.

Introduction to the Problem

Mental illnesses have become a global burden. Almost every family is affected by mental illnesses, either

directly as individuals, or indirectly in the manner that the family has to live with and care for relatives

who are suffering from a mental illness particularly where disability has resulted from such mental illness.

There are many different mental illnesses (also called mental disorders), chiefly characterized by disturbed

thoughts, perceptions, emotions, behaviour and disturbed interpersonal relationships. These disorders include

depression, bipolar affective disorder/mania, schizophrenia, psychosis, dementia, intellectual disabilities and

developmental disorders including autism [1-3]. Though some disorders have a pathological aetiology, factors

such as significant events like death of a loved one, loss of income, poverty, unemployment, interpersonal

conflicts, alcohol and drug use related disorders also play a significant role in the development of mental

illness [1,4].

Globally, depression is the most common mental disorder and the major cause of disability worldwide, of which about 300 million people are suffering from depression [3]. According to the WHO Global Health Estimates Report for 2015, there were 169 427 404 of mental and substance use disorders recorded. Among those recorded cases, depressive disorders accounted for 31%, anxiety disorders 15%, drug use disorders 10%, schizophrenia 9%, alcohol use disorders 8%, other mental and behavioural disorders accounted for 6%. In Africa, 19 424 682 cases were recorded. Depressive disorders were the highest disease burden at 37%, followed by anxiety disorders (14%), drug use disorders (8%), alcohol use disorders (6%), schizophrenia (6%), Bipolar disorders (5%) and other mental and behavioural disorders constituted 5%. Available report for Sub-Saharan Africa revealed that in 2013, 21 490 590 cases recorded. Forty percent (40%) of those cases were depressive disorders, anxiety disorders 11%, drug use disorders 10%, alcohol use disorders 8%, schizophrenia 6%, conduct disorders 5%, while other mental disorders constituted 4% [3,5,6].

Given the fact that mental disorders tend to be chronic, disability can occur, thus requiring that an individual be cared for by his/her family. However, caring for a family member with a mental disorder places an enormous burden on family caregivers and has been shown to have a significant impact on the family’s quality of life. In the sub-Saharan Africa and probably in Africa as a whole, the stigma attached to mental illness is deeply rooted in cultural beliefs, where mental illness is associated with witchcraft. Not only that mental illness is a witchcraft illness, but there is also societal stigmatization of those who are mentally ill and their families. This include being mocked as “insane, “insane”, “mad” or Chizede and Chipuba in local language’ [7-9].

Apart from stigmatization, mentally ill persons are discriminated, whereby their employment maybe terminated due to their illness, thus resulting in social and economic hardships. Furthermore, with the stigmatization, the person or his/her family cannot seek medical help due to fear of being stigmatized and discriminated, eventually resulting in reduced quality of life [7,10,11]. On the family aspect, caring for a family member with mental illness is associated with stress, frustrations, interpersonal conflicts particularly between patient and care givers due to aggressive behaviours of their patient, regular financial expenditures involved in health care of the patient including medicine, going for follow ups, absenting from work when needed, just to mention a few. More often than not, in African societies, females bear the most of the burden, thus they have to redefine their roles to accommodate the caregiver roles, in addition to already existing roles that the society expect them to fulfil [8,9].

It has been observed though statistical review and analysis of the Patient Register Books for Psychiatry

Outpatient Clinic (clinic 6) of the University Teaching Hospital, that there is a significant rise in the

number of mental illness cases. In 2016, there were 2334 mental illness cases recorded, which is a 25.6%

increase from cases recorded in 2015 (1857 cases). In addition, the World Health Organization revealed that

the mental illness diseases burden which is assessed in terms of Disability-Adjusted Life for Years (DALY)

for Zambia was 1000 per 100 000 people [12]. This reflects that mental illnesses greatly affect the social

and occupational functioning of an individual resulting in disability such as inability to care for self, loss of

productivity, poor performance at work as well as difficulties in interaction with those around them.

However, despite the growing numbers of mental illness that directly resulted in the increase in population of families living with mentally ill patients, there has been no recent studies focusing on the experiences of families caring for persons with mental illnesses in Zambia. There are no studies pertaining to the challenges they are facing, no interventions or programs in place that are aimed at supporting the families, whether in terms of buying medicine, accessing the health services, tracing of defaulters or regular house visits. Hence, these families endure the journey of caring for their mentally ill patients on their own despite the psychological, financial and social effects that come with taking care of a person with a chronic condition. Thus, it is upon this rationale that the study was conducted to explore and describe the lived experiences of the families caring for a mentally ill relative, describe the role caregivers play in the care of their loved ones, as well as to identify challenges caregivers face, and find possible interventions to support them in the care of their loved ones.

The aim of the study was to describe the experiences of the families who are caring for persons diagnosed

with mental illnesses being followed up at the University Teaching Hospital Psychiatric Clinic (clinic 6) and

develop health interventions to support these families.

The specific objectives of the study were:

1. To describe the caregivers’ experiences of living and caring for a mental ill relative (psychosocial feelings/

perceptions)

2. To identify challenges faced by family in caring for a mentally ill relative

3. To identify coping mechanisms and support systems available to families living with mentally ill relative

The study aims to answer the following research questions:

- What are the perceptions of caregivers towards caring for a mentally ill relative?

- What roles and responsibilities do caregivers perform?

- What are the support systems available to these families to cope with the challenges they are faced with?

The study was conducted at UTH Psychiatric Clinic (Clinic 6). This site was selected because the researcher

is familiar with the setting, and it because it is also the place where the research participants accompany their

relatives for follow ups.

This research study was significant because the information gathered can be used to develop interventions

that will assist the patient themselves as well as their families to address their burdens and help them deal

with the problems that they have encountered in a healthy manner.

Literature Review

In the process of searching for information relevant to the study, both primary and secondary sources were

used. Primary sources studied were families who were caring for relatives with mental illness. Secondary

sources included various books, articles and journal on mental illnesses, previous research studies on the

experiences and perceptions of families caring for mentally ill persons, family and caregiver roles, as well as

constrains encountered (psychological, social or economic) in the care of a mentally ill person [13].

Mental illness (also called mental disorder) is group of disorders that encompasses conditions including

brain diseases (dementia, schizophrenia, psychosis, cerebral palsy), common mental disorders (CMD)

that include anxiety (including general anxiety disorders, phobias, obsessive compulsive disorders (OCD),

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depressive illness and mood disorders such as mania, somatoform

disorders, developmental disorder (including mental retardation, autism, intellectual disability), behavioural

disorders (for example Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD), conduct disorders) personality

disorders, as well as substance abuse and dependence (alcohol abuse and/or drug abuse). Mental illnesses are

chiefly characterized by disturbed thoughts, perceptions, emotions, behaviour and disturbed interpersonal

relationships [1,2,4].

The aetiology of mental illness is believed to be of biopsychosocial origin. Mental illness is thought to result from a pathology in the brain, that is attributed to chemical imbalance in the brain, either resulting from brain anatomy disturbances (for example trauma to the head) or medications that disturb the chemical levels of the brain such as anti-dopaminergics. Another aspect of aetiology stems from the psychosocial dimension. Past and present personal stressors for example, death of a loved one, abuse during childhood, unemployment amongst others can result in mental illness. In the same vein, interpersonal conflicts, alcohol and drug abuse contribute to development of mental illness. Heredity and genetics also play a greater role in the development of mental illness, as mental illness can run in some families [1,4].

Statistically, according to the outpatient register books at UTH Psychiatric Clinic (clinic 6), 2334 mental illness cases were recorded at University Teaching Hospital Psychiatric Clinic (clinic 6) in 2016, which is a 25.6% increase from cases recorded in 2015 (1857 cases). The top five (5) recorded cases were: Seizure disorders (15.5%), Alcohol and Substance abuse (11.5%), Brief Psychotic Disorders (10.6%), Schizophrenia (9.3%), and Depressive illness (6.1%).

Since mental illness tend to be chronic, patients often live with their families. For this reason, chronic mental

illness negatively affects not only the patient but also the family. This require that family members add

another burden of a role, particular females. Usually, caregiving role is culturally and socially determined, and

this is true of African societies, whereby one or more of the family members has to take up the caregiver role,

usually without being paid for it. Generally, the caregiving role is accompanied by role strain, role conflicts

and role overloading, meaning they have to perform a number of roles at once. In so doing, the caregivers

may also experience difficulties, that might as well have a negative impact on their daily lives particularly

anxiety and depression [8,14,15].

Another effect of mental illness is felt on the economic aspect. In a study by Iseselo, Kajula and Yahya-Malima (2016) [9] that studied the psychosocial problems of families caring for relatives with mental illnesses, it was found that these families experienced financial constraints related to cost of medication and transport, disrupted household routines, conflicts with the neighbours as well as stigma and discrimination, and used various coping mechanism. In addition to the financial constraints, disturbed behaviours, particularly verbal and physical aggression and refusal of the patient to take medicine or go to hospital, also affected the family in different ways. To deal with these constrains, they employed various coping mechanisms [16].

The care giving role is usually culturally and socially determined, based on the cultural and social norms of

a given society. In many instances, due to the presence of illness in the family, family members especially

women have either to re-define or add to their family role so that they provide meticulous care to their ill

loved ones. This is also true to mental illness [17]. Because mental illness causes morbidity and tend to be

chronic in nature, these families have to care for their relatives, who are many a time dependent on them

for normal living. Therefore, the care giving role creates a burden to these care givers, which also has its own

toll on the daily living of the care givers. The caregivers have to balance their social lives and caring for their

relatives, where often they have to sacrifice their social lives [14,15].

Caregiver burden is defined as any physical, psychological, emotional and/or financial problems that caregivers

experience whilst caring for their mentally ill relative [18]. The caregiving role is not just a strenuous, daunting

task, but in itself is a stressful task, and hence it qualifies to be referred to as a stressor. The role entails general

monitoring of the mentally ill relative’s well-being, ranging from medication administration, performing

daily activities for the patient based on morbidity level, identifying relapse, taking patient for follow- ups,

and providing social and psychological support to the patient amongst others. Role strain, role conflict and

role overload may also be endured. All these culminate into in grieving, stress and depression among others

[17,19]. In addition, caregivers also suffer psychologically as a result of social stigmatization associated with

mental illness, and experience anxiety and frustration particularly when the patient is exhibiting problematic

behaviours such as aggression, destructive behaviour or wandering around [17,18,20].

Socially, most of the time, the caregivers have to re-adjust their lifestyles, to avail more time and thus be able to care for their relatives effectively. This ranges from resigning from their jobs, taking up part-time jobs (i.e. giving up fulltime job), and cutting-down on social gatherings such as weddings and funerals. For instance, one will opt to miss a wedding or party because she/he cannot leave his relative unattended [19,20].

In a study by Bemdeli (2017) [8], it was revealed that caregivers experienced emotional instability such as depression, anxiety (especially if the patient has aggressive behaviour episodes), burnout, stress, shame, guilt, strain, anger, social isolation and feelings of helplessness. Furthermore, societal stigmatization and interfamilial conflicts also contribute to emotional instability. The families can also be physically harmed, particularly if the patient has problematic behaviours [21,20].

Pertaining to coping mechanism, caregivers turn to spiritual and religious coping mechanisms, mainly dealing with their problems through prayers [21]. In a study by Ndetei et al. (2009) [16], participant caregivers mainly used prayer, ignoring and asking for external help. For instance, in terms of problematic behaviours, specifically wandering, taking the patient to hospital or when patient is destructive, eleven percent (11%) of the caregivers prayed, eighteen percent (18%) ignored the patient’s behaviours, sixteen percent (16%) forced/restrained the patient, forty-eight percent (48%), whereas five percent (5%) didn’t know what to do [16]. Another study by Mokgothu et al. (2015) [22], revealed that as coping mechanisms, eighty-nine percent (89%) of the caregivers making use of external resources such as neighbours, police services, seventyeight percent (78%) made use of spiritual and faith whereas eleven percent (11%) coped through acceptance.

Caring for the mentally ill patient is no doubt a financial burden. Family members usually have to bear the

costs for medications as well as hospital transport costs, more so without reimbursement [18,19]. These

individuals’ morbidity might be at different levels, where some are affected mildly, moderately and/or severely

such that their social and economic productivity is also affected. Some patients might have lost their jobs,

while on the other hand, the caregivers might also have either given up their jobs to care for their relatives,

have taken part-time jobs, or have lost money in forms of reimbursement of persons whose properties

were damaged by these mentally ill patients, or even though repairing their own damaged properties (e.g.

household items) [16].

Treatment cost is also a major financial challenge, of which families can be affected in various degrees- some mildly, moderately or severely, depending on the income and availability of funds of a particular family [9]. Ndetei et al. (2009) [16], found out that forty-two (42%) of the families studied were moderately affected financially, with thirty percent (30%) severely affected. Twenty percent (20%) of the households were moderately affected by repair costs while thirty-five percent (35%) were severely affected by such costs.

Financial challenges are not only a challenge to the families, but also to most of African governments. According to Daar et al., (2014) [23], only less than one percent (1%) of the health budget is spent on Mental Health Services. Therefore, WHO has adopted the Mental Health Action Plan (MHAP) 2013- 2020, that amongst its objectives, calls for integration of Mental Health Care services into Primary Health Care, address stigma and human rights violations.

The objectives of the MHAP are:

1) To strengthen effective leadership and governance for mental health

2) To provide comprehensive, integrated and responsive mental health and social care services in communitybased

settings

3) To implement strategies for promotion and prevention in mental health

4) To strengthen information systems, evidence and research for mental health (WHO 2013).

Furthermore, in a study by Munakampe (2016) [24], it was identified that financial constraints in terms of inadequate financing of mental health services is the main barrier to utilization of mental health services in Zambia. These services are hindered by insufficient financing as well as low prioritization, that has led to the lack of mental health services provision at the primary level. Worse more, inadequate funding has led to failure of mental health outreach programs to kick off, thus utilization of mental health care began at secondary level.

Therefore, for these families’ financial burden to lessen, there is need to improve financing for mental health services, to strengthen service provision at primary level so that the mental health services are brought to the community and to the door-steps of the patients, subsequently reducing patient and families’ financial costs [24,25].

Mental illness is greatly associated with societal stigmatization. In the sub-Saharan Africa and probably in

Africa as a whole, the stigma attached to mental illness is deeply rooted in cultural beliefs, where mental

illness is associated with witchcraft. Not only that mental illness is a witchcraft illness, but there is also

societal stigmatization of those who are mentally ill and their families. This include being mocked as “insane,

“insane”, “mad” or Chizede and Chipuba in local language’ [7-9].

Pātil et al. (2013) [4] defines stigmatization as any attribute, character or disorder that label an individual as being unacceptably different from the normal person, with whom he/she routinely interacts with, resulting in some form of community sanction. As a result of this social unacceptance and sanctioning, the individual’s social participation is reduced. Worse more, social relationships with neighbours and society at large are disturbed, and the same stigmatizations has resulted in strained relationships within some families themselves because some family members do not like to be associated with a mentally ill relative- all because of stigmatization [4,10].

In a study by Amuyunzu-Nyamongo (2013) [7], it was found out that in many Africa societies, many households with mentally ill persons hide them for fear of discrimination and mockery from their communities. Negative blames to these families and social sanctioning or simply the stigma attached to mental illness has led to delay in medical treatment seeking and consequently to a poor quality of life [4,11]. Furthermore, because of gender based discrimination, particularly to women, girls from families known to have mental illness find it difficult to get spouses, eventually reducing their opportunities to be married.

Research Methodology

A qualitative research design employs questions such as “how?” or “why?” to describe a natural or a social

phenomenon (Houser 2018). Qualitative research focuses on the meaning of a phenomenon under study

with the aim of gaining insight and understanding, so that the researcher understands how people interpret

their experiences and the meanings they attach to these experiences (Houser 2011) [26,27]. Qualitative

design was favoured because it allows the researcher to gain an in-depth description and understanding of

experiences from the families who are caring for mentally ill persons (Houser 2018).

Phenomenology is the study of human experiences; so that one understands the meanings of experiences each

individual or respondent - basically, their perceptions, understandings and beliefs concerning a particular

situation. A phenomenological approach allows direct investigation and description of the phenomenon

as consciously experienced and narrated by those who have lived it (Mertens, 2009) [26,28,29]. Therefore,

based on the descriptions of phenomenology, the researcher opted to use the phenomenological paradigm,

because it will pave way for her to clearly understand the experiences of the families caring for mentally ill

persons, the role these caregivers play as well as challenges they are facing in the care of their loved ones.

Descriptive research is conducted to describe the experiences of the participants in a particular setting or

towards a particular event. It gives a detailed description or account of the setting/phenomenon/context

[30-32]. Descriptive design was used in this study to give a clear picture so that the readers of the research

report could coherently understand the experiences of families caring for mentally ill persons. Direct quotes

were used to show the participants’ responses.

“Population” (also referred to as target group) refers to a group of subjects that contains features of interest

to the researcher, that meets specified characters pre-determined by the researcher [33,34]. The population

consisted of families (relatives and care givers) of patients who are being followed up in Psychiatric Clinic

(clinic 6) of UTH.

A sample is a selected subset from the population, that represents or reflects composition of the target

population. The sample was selected using non-probability purposive sampling, where the sample is selected

because it contains characteristics that are representative of the population. The researcher has purposively

selected the sampling method based on judgment that these families have been caring for their relatives for

some time, so they are can provide data from their daily personal experience. Criterion sampling was used

to determine the families to be included or excluded from being part of the study (Houser 2018) [33,34].

• Only those families (biological related persons- parents, aunts, uncle, sister, brother, cousin, in-laws) who

has been caring for their relatives three (3) months or more are eligible to be study participants.

• Any family (biologically related persons) living or caring for a mentally retarded relative for less than three

(3) months

• Persons who are non- biologically related to the patient

The three (3) months’ time frame was favoured because the researcher believe that by this time that family or care givers have at least made abstracts from the daily care of their loved ones [33,34].

According to various authors, sample size is of less significance in qualitative research. Qualitative studies

are not intended for generalisation to large populations, but they are intended to provide a “thick” and

meaningful description in order to increase existing knowledge of the phenomenon under investigation

[28,35]. Various authors are in agreement that there is no definite sample size for qualitative research to gain

significance. The sample consisted of four families, as data became saturated, and that was observed when

there was no more newer information to be obtained from increasing the sample [29,36,37].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Data was collected to explore and describe the experience of caregivers related to living and caring for a

mentally ill relative. The findings were supported by verbatim quotes from the interviews and after discussion

of each themes and categories, relevant literature was used to substantiate the discussed data.

Tesch’s coding system was used to organise the data into themes and categories using the following steps:

1. Getting a sense of the whole: The interview transcripts were read through one at a time, in the order that

the interviews had been conducted (i.e. first, second, third till the eighth).

2. Identifying topics: The researcher identified topics to organise the ideas from the collected data.

3. Identifying categories: The rectangular pieces of papers with ideas from the first step were then placed

in the columns. Data with similar meanings were grouped together, and placed in columns. Thereafter,

categories were developed.

Identifying themes: The categories were blended into concepts that could be seen as research outcomes. Four themes were developed, which best revealed the experiences families who care for mentally ill relatives being followed up at Psychiatric Clinic at UTH, Lusaka [38-42]. Italicized direct quotes were included as they narrated in the transcribed interviews. An extract from an interview is included (Appendix G) in the research report. Data that was collected was analysed as appearing in the next paragraphs.

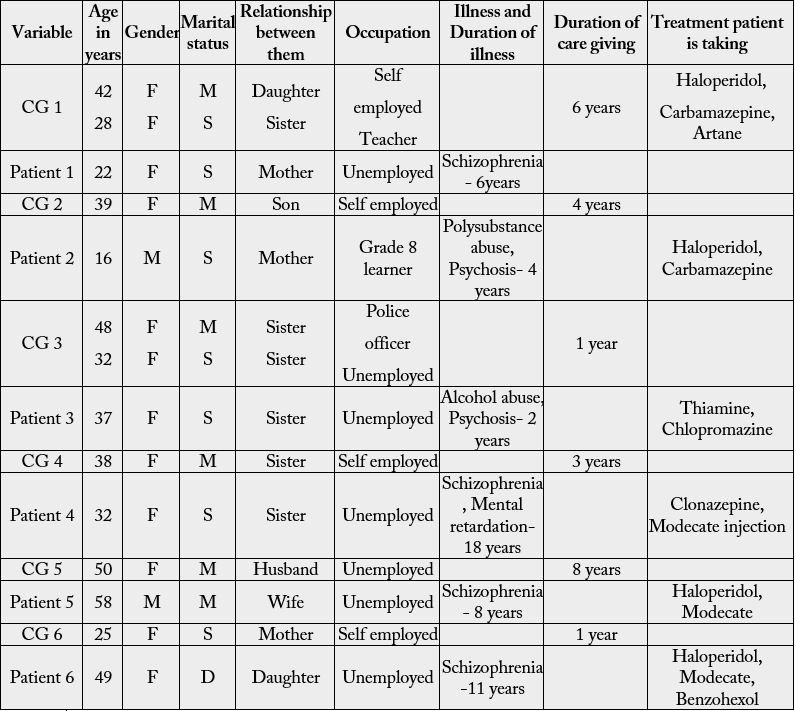

KEY: CG- Caregiver F-Female M-Male M-Married S-Single D-Divorced

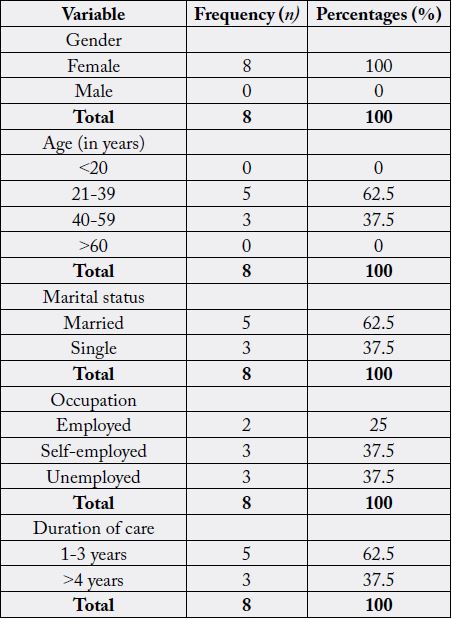

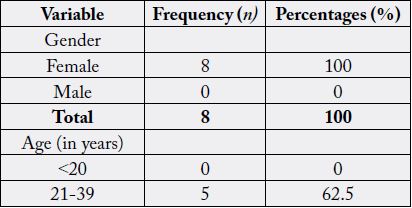

Six families comprised of eight (8) caregivers were studied. All family caregivers (100%) who participated in the study were females, aged between 25-50 years old, with the mean age of thirty-eight (38) years of age. Five (62.5%) of the caregivers were married, and three (37.5%) were single. The above information is summarized in the table underneath (table 2(a)).

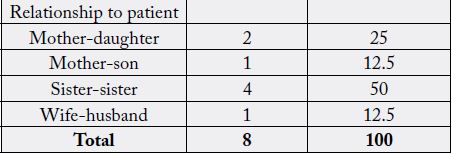

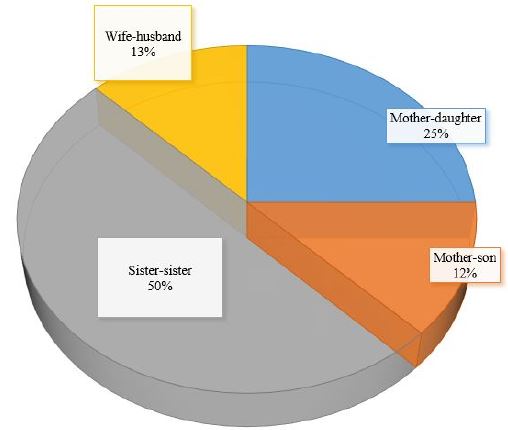

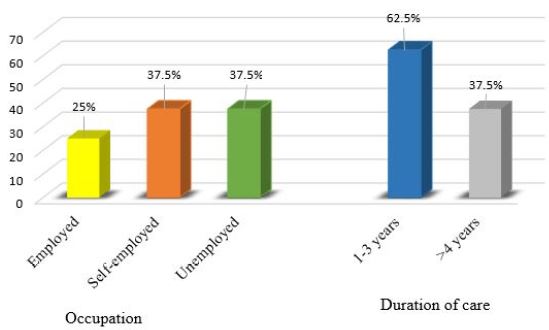

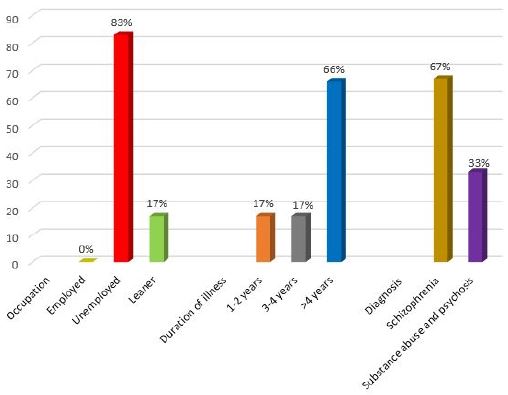

Amongst those caregivers, only two (25%) were employed, three (37.5%) were self- employed while the other three (37.5%) were unemployed. Three (37.5%) of these relatives have been caring for their relatives for a duration of 1 year, one (12.5%) for 3 years, another one (12.5%) caregiver provided care for 4 years, while the other three (37.5%) caregivers did the same for more than 4 years. Caregivers were related to the patients as mothers (25%), sisters (50%), son (12.5%) and wife (12.5%). They have been caring Two (25%) of the relatives have been caring for their patients from the time the patient was diagnosed with mental illness, whereas six (75%) of the caregivers rotated caring for the patient among the family members including cousins, brothers, sisters, aunts amongst others. The diagrams (Figures 1 and 2) below display the graphic presentation of relationship of caregivers to the patients, occupation and duration of care.

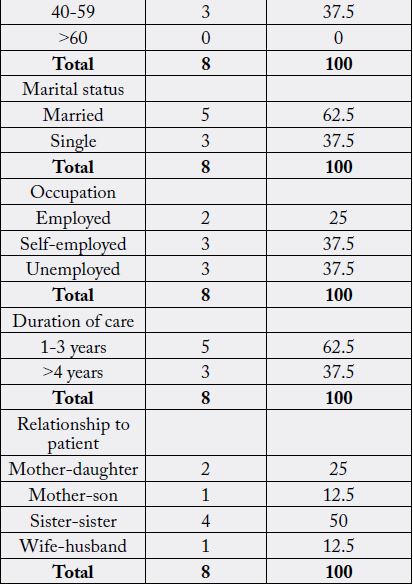

Patients were predominantly females- four (67%) and two (33%) males. Their ages ranged between 16- 58 years, with a mean age of 36 years. Only one patient (17%) who is a male patient, was married. Four (66%) were single, while one (17%) who is a female was divorced. Five of the patients (83%) were not employed, and one patient (17%) was a learner. Four patients (67%) were diagnosed with Schizophrenia, the remaining two (33%) were Substance abuse and Psychosis cases. Two (33%) patients have been diagnosed with substance abuse and psychosis 2-4 years now since the first diagnosis was made, and four (67%) have been living with schizophrenia for more than 4 years, amongst which one patient has been living with schizophrenia for 18 years. They are all taking daily oral medications, with some (50%) taking monthly injections in addition to the oral medications. Table D below summarizes the above information. The above information is presented in table 2(b) as well as in diagrams figure 3 as well as figure 4.

Four themes were developed from the interviews. Figure 5. below provides an outline of the developed

themes and categories.

According to the families interviewed, five (62.5%) caregivers found caring for a mentally ill patient is a

difficult, one (12.5%) found it hectic and two (25%) found it a challenging task which requires tolerance.

The main difficulty was the unpredictable behaviors of the patient, particularly when the patient is in acute

states of the illness as well as the monitoring because most of the time these patients cannot be left alone.

Caregivers play an important role in the lives of their patients. As these patients are chronically mentally

unstable, five (62.5%) of the caregivers revealed that they have a responsibility to feed the patients, either by providing meals or feed with a spoon when their patients refuse to eat keep, two (25%) assist their patients

clean by providing bathing water and/or bathing them, while one (12.5%) assists with doing the laundry.

All caregivers revealed they supervise their patients when the patients are performing basic activities as their

patients sometimes are reluctant to bath or even eat when left alone.

Two families (25%) endured societal discrimination and labelling due to mental illness. Half (50%) of the

caregivers also experience stress and psychological disturbances. Six caregivers (75%) experienced financial

difficulties because these patients have regular monthly follow ups, and there is little time to make income

due to the supervisory role that they play i.e. they cannot leave the patients alone while they are going to

the market to sell some goods to make money. Three care givers (37.5%) revealed that even if they are selfemployed,

the income is not sufficient to cater for these families’ needs.

Families employed various coping mechanisms to deal with the challenges they are faced with in the care

of their loved ones. Four family members (50%) have accepted that it is God’s will that their relative is

mentally ill, while all families (100%) used prayer as a coping mechanism. During the times their patients

are aggressive, all families (100%) relied on neighbour support to restrain or take the patient to the hospital.

Financially, some families have settled with selling goods at the roadside due to the fact that patient cannot

be left alone at home, while others (37.5%) have resorted to self-employment to make money for transport

for monthly hospital follow-ups.

Among the respondents, six caregivers (75%) would like to be assisted with financial means to enable them

to take patient to hospital and buy medicine, as well as to adequately care for their patients. They suggested

cash grants (social financial grants) and food aid handouts from the government or non-governmental

organizations so that they are able to feed and clothe their patients. Food for work programs were also a

suggested option.

Discussion

The data revealed that caring for a mentally ill patient is a hectic and challenging task. Furthermore, families

play an important role in the care of their loved ones, particularly that these persons depend much on their

relatives to attain basic daily needs such as having meals, bathing, and hygiene. They also require supervision

when performing some of the daily activities. In addition, the families endure societal discrimination

and labelling due to mental illness, experiences stress and psychological disturbances as well as financial

difficulties because these patients have regular monthly follow ups, and there is little time to make income

due to the supervisory role that they play i.e. they cannot leave the patients alone while they are going to

the market to sell some goods to make money. Families employed various methods of coping, ranging from acceptance, prayer, rotation of care among the relatives as well as selling a few things to generate income.

Lastly, it was revealed that caregivers need social support in the form of grants, food aid or food for work in

order to effectively care for their mentally ill relatives.

Since mental illness tend to be chronic, disability can occur, thus requiring that an individual be cared for

by his/her family. However, caring for a family member with a mental disorder places an enormous burden

on family caregivers and has been shown to have a significant impact on the family’s quality of life [7-9].

According to the families interviewed, caring for a mentally ill patient is a hectic and challenging task. The families revealed that they find it difficult to handle their patients when they are violent, and most of the times these patients have unpredictable behaviors, where they have to call in neighbors for help to restraint the patient and take them to the hospital. Some refuses to eat or bath, and caregivers have to spend their precious time convincing their loved ones to eat, or even to feed them with a spoon. Even basic activities such as bathing or eating requires supervision, otherwise these patients will not complete these tasks. The following quotes support the above findings:

“It’s a very difficult task in terms of handling him. At times, he becomes violent, and at times he is just a normal person. He has very unpredictable behaviors. So, I have to call the neighbors for help or even the police sometimes, so that we can take him to the hospital.”

“It is very hectic. She needs to be supervised most of the times including when I tell her to go bath, or when taking medicine because there are times she refuses. I have to make sure that she has swallowed the medicine, so I have to convince her to take medicine. Sometimes I even spend hours waiting for her to finish eating or bathing, otherwise I am not around, she won’t eat or bath.”

Ndetei (2009) [16] argues that it is difficult to stay with a mentally ill patient. They exhibit various disturbed behaviors, particularly physical and verbal aggression, which has also been revealed from this study.

Families play an important role in the care of their loved ones. These persons depend much on their relatives

to attain basic daily needs such as having meals, bathing, and hygiene. Caregivers provide meals, assist with

bathing and feeding, toileting and cleaning the surrounding where the patient lives as well as doing laundry

for them. The quotes bellow supports the above statements:

“I make sure that she bathes every day. But there are days that she refuses to bath, so I have to bath her myself because she is my sister. When it comes to meals, she sometimes eats well, she can also just sit there staring at the food…. she will not eat even if you tell her to eat. That is when I have to feed her with a spoon”.

“There is a lot that I do for him. Sometimes he defecates on himself or defecate anywhere in the house, and I have to bath him and clean the house.

“I make sure that she takes medicine every day and take her every month to the hospital for her injection. The problem is…. if she spent time without medication, she becomes violent and behaves strange”.

The care giving role is usually culturally and socially determined, based on the cultural and social norms of a given society. In many instances, due to the presence of illness in the family, family members especially women have either to re-define or add to their family role so that they provide meticulous care to their ill loved ones. This is also true to mental illness, particularly in our African settings [17]. Because mental illness causes morbidity and tend to be chronic in nature, these families have to care for their relatives, who are many a time dependent on them for normal living. Therefore, the care giving role creates a burden to these care givers, which also has its own toll on the daily living of the care givers. The care givers have to balance their social lives and caring for their relatives, where often they have to sacrifice their social lives [14,15]. Socially, most of the time, the caregivers have to re-adjust their lifestyles, to avail more time and thus be able to care for their relatives effectively. This ranges from resigning from their jobs, taking up part-time jobs (i.e. giving up fulltime job), and cutting-down on social gatherings such as weddings and funerals. For instance, one will opt to miss a wedding or party because she/he cannot leave his relative unattended [19].

Families endure societal discrimination and labelling due to mental illness. Their households and house members, even the children are labelled as if they are also mentally ill.

“The way these people in our compound sometimes treat us is like we are all mad in our house. The house has no owner anymore. Most of the time is associated with my mentally ill sister. So, the house is now the house of the mad one”.

“There are times my sister is not insane. But still, people will run away from her, and lock themselves in their houses. Therefore, we keep her inside the house to avoid all these”.

Mental illness is greatly associated with societal stigmatization. Pātil et al. (2013) [4] defines stigmatization as any attribute, character or disorder that label an individual as being unacceptably different from the normal person, with whom he/she routinely interacts with, resulting in some form of community sanction. As a result of this social unacceptance and sanctioning, the individual’s social participation is reduced. Worse more, social relationships with neighbours and society at large are disturbed, and the same stigmatizations has resulted in strained relationships within some families themselves because some family members do not like to be associated with a mentally ill relative- all because of stigmatization [4,10].

In a study by Amuyunzu-Nyamongo (2013) [7], it was found out that in many Africa societies, many households with mentally ill persons hide them for fear of discrimination and mockery from their communities. Negative blames to these families and social sanctioning or simply the stigma attached to mental illness has led to delay in medical treatment seeking and consequently to a poor quality of life [4,11]. Furthermore, because of gender based discrimination, particularly to women, girls from families known to have mental illness find it difficult to get spouses, eventually reducing their opportunities to be married.

Caring for the mentally ill person is also psychologically disturbing. Some families have found it difficult

to accept that their relatives are mentally ill, and becomes stressed as have to live with their patients in such

insane states.

“It is difficult and very stressing to see my own son who has just grown up like all other normal children, and all of a sudden he is talking nonsense and wanting to beat me up. All from nowhere! You know…. I just can’t believe that he is insane. Even in the night I wake up as if I am still living a dream.”

“Most of my time, my thoughts are occupied with my sister’s sickness. When she is showing those signs that she is becoming sick [in the acute illness state], it becomes even more worse- I start panicking and anxious as I know the worst is about to happen.”

In a study by Bemdeli (2017) [8], it was revealed that caregivers experienced emotional instability such as depression, anxiety (especially if the patient has aggressive behaviour episodes), burnout, stress, shame, guilt, strain, anger, social isolation and feelings of helplessness. Furthermore, societal stigmatization and interfamilial conflicts also contribute to emotional instability. The families can also be physically harmed, particularly if the patient has problematic behaviours [21].

On the other hand, families found it financially challenging to care for their mentally ill relatives. Some

patients have lost employment or have lost the capability to be self-employed hence they have become

dependent on their relatives virtually for all their needs. There are times the families are faced with buying

medicine if the hospital has run out of medicines, and have to go for follow-up monthly. Furthermore,

because of the supervisory role, time for money generation becomes little, making it difficult to generate

sufficient income to support these families. This can be attested by the following quotes:

“He use to work as a builder. Now that he is sick, he hardly does any productive work. I use to sell a few things at the market, but I dropped because there is no one to stay with him at home. Now I just sell vegetables and Munkoyo [traditional drink] outside the house at the road there…. But this is not as good as the market, because at the market customers are many”.

“The problem is that my sister has to go to the hospital every month. So, we have to look for money for transport to and from hospital every month. And sometimes we are told the medicine is finished. There is no other option, we have to buy. At the end of the day, I use up all that I have”.

Caring for the mentally ill patient is no doubt a financial burden. Family members usually have to bear the costs for medications as well as hospital transport costs, more so without reimbursement [19,18]. These individuals’ morbidity might be at different levels, where some are affected mildly, moderately and/or severely such that their social and economic productivity is also affected. Some patients might have lost their jobs, while on the other hand, the caregivers might also have either given up their jobs to care for their relatives, have taken part-time jobs, or have lost money in forms of reimbursement of persons whose properties were damaged by these mentally ill patients, or even though repairing their own damaged properties (e.g. household items) [16].

Treatment cost is also a major financial challenge, of which families can be affected in various degrees- some mildly, moderately or severely, depending on the income and availability of funds of a particular family [9]. Ndetei et al. (2009) [16], found out that forty-two (42%) of the families studied were moderately affected financially, with thirty percent (30%) severely affected. Twenty percent (20%) of the households were moderately affected by repair costs while thirty-five percent (35%) were severely affected by such costs [16].

Families employed various methods of coping, ranging from acceptance, prayer, rotation of care among the

relatives as well as selling a few things to generate income.

“I have accepted that my sister is sick. I just pray to God and hope she gets better”.

“We pray a lot…. Prayer is a great weapon for us, and believe God will surely hear our prayers”.

“We use to share the responsibility of caring in the family. The past 1 year she was staying with my elder sister. So next we will see who will take her for care”.

“When my mother become sick, I was forced to find some sort income. That is how I started to sell just at the roadside near the house”.

Pertaining to coping mechanism, caregivers turn to spiritual and religious coping mechanisms, mainly dealing with their problems through prayers [21]. In a study by Ndetei et al. (2009) [16], participant caregivers mainly used prayer, ignoring and asking for external help. For instance, in terms of problematic behaviours, specifically wandering, taking the patient to hospital or when patient is destructive, eleven percent (11%) of the caregivers prayed, eighteen percent (18%) ignored the patient’s behaviours, sixteen percent (16%) forced/restrained the patient, forty-eight percent (48%), whereas five percent (5%) didn’t know what to do [16]. Another study by Mokgothu et al. (2015) [22], revealed that as coping mechanisms, eighty-nine percent (89%) of the caregivers making use of external resources such as neighbours, police services, seventyeight percent (78%) made use of spiritual and faith whereas eleven percent (11%) coped through acceptance.

Caregivers would like to be assisted with financial means to enable them to take patient to hospital and buy

medicine, as well as to adequately care for their patients. They suggested cash grants (social financial grants) and food aid handouts from the government or non-governmental organizations so that they are able to

feed and clothe their patients. Food for work programs were also a suggested option. This can be attested by

the following quotes:

“I feel it would be better if the government would come up with a certain organization that would help families with mentally ill people in the form of money or social support like social or cash grants”.

“I am asking for the Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to come in and help us either with food relief or food for work programs so that we can be able to take patient for follow-up and buy medicine as needed

As mentioned early in that caring for a mentally ill comes with economic hardships, there is a need for financial aid to supplement the family care. Family members usually have to bear the costs for medications as well as hospital transport costs, without reimbursement [16,18,19]. Hence, it is imperative that they have are financially and socially assisted.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The aim of the study was to describe the experiences of the families who are caring for persons diagnosed

with mental illnesses being followed up at the University Teaching Hospital Psychiatric Clinic (clinic 6)

and develop health interventions to support these families. The objectives of the study were to describe the

caregivers’ experiences of living and caring for a mental ill relative (psychosocial feelings/perceptions), identify

challenges faced by family in caring for a mentally ill relative as well as to identify coping mechanisms and

support systems available to families living with mentally ill relative.

The study was undertaken as a qualitative, descriptive, using a phenomenological approach and the population consisted of families (relatives and care givers) of patients who are being followed up in Psychiatric Clinic (clinic 6) of UTH. This approach was used to allow the researcher study the lived experiences of caregivers. Purposive sampling was used. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were designed to aid in selection of the sample. Six families comprised of eight (8) caregivers who were all females, were studied. In-depth interviews were conducted using open ended questions and using the developed data collection tool (Annexure I). Data was analysed using Qualitative Data Analysis (QDA) Miner Lite).

Five themes were developed from the study:

Mental illness negatively affects not only the patient but also the whole family. This require that family

members add another burden of a role, particularly females. Caregiver burden is defined as any physical,

psychological, emotional and/or financial problems that caregivers experience whilst caring for their mentally

ill relative [18]. The caregiving role is not just a strenuous, daunting task, but in itself is a stressful task, and

hence it qualifies to be referred to as a stressor. The role entails general monitoring of the mentally ill relative’s

well-being, ranging from medication administration, performing daily activities for the patient based on

morbidity level, identifying relapse, taking patient for follow- ups, and providing social and psychological

support to the patient amongst others. Role strain, role conflict and role overload may also be endured

[17,19].

Usually, caregiving role is culturally and socially determined, and this is true of African societies, whereby one or more of the family members has to take up the caregiver role, usually without being paid for it. Generally, the caregiving role is accompanied by role strain, role conflicts and role overloading- meaning they have to perform a number of roles at once. In so doing, the caregivers may also experience difficulties, that might as well have a negative impact on their daily lives particularly anxiety and depression [8,14,15]. Therefore, the care giving role creates a burden to these care givers, which also has its own toll on the daily living of the care givers. The care givers have to balance their social lives and caring for their relatives, where often they have to sacrifice their social lives [14,15]. This caregiving role, caregiver burden, role conflict, role strain as well as sacrificing social lives was also evident from this study results.

Pertaining to coping mechanism, caregivers turn to spiritual and religious coping mechanisms, mainly dealing with their problems through prayers [21]. In a study by Ndetei et al. (2009) [16], participant caregivers mainly used prayer, ignoring and asking for external help. Another study by Mokgothu et al. (2015) [22], revealed that as coping mechanisms, caregivers making use of external resources such as neighbours, police services, spiritual and faith services, whereas others coped through acceptance. Evidently from this study, all families turned to prayer as a main coping mechanism, some made use of neighbour’s support, while others have to find ways of generating income to enable them to make ends meet in provision of care to their patients.

Based on the study results, it is recommended that:

1) Mobile/outreach mental health care services to bring mental health care services to the community at identified spots/points whereby medicine can be brought to these patients. With such mobile mental health care services, transport cost for regular follow-ups are minimized as the health care provision team is meeting the community halfway, and eventually strengthen collaboration between the health care providers, families and the community at large. Therefore, routine mobile mental health care services will more economically beneficial to the patients and their families. It does not only help the in reducing the economic challenges, but also enable the mental health care provision team to trace defaulters, monitor patient adherence to treatment and consequently reduce occurrence of relapses. This is in line with the WHO Mental Health Action Plan (MHAP) 2013-2020, that amongst its objectives, calls for integration of Mental Health Care services into Primary Health Care, address stigma and human rights violations [25].

2) Educational campaigns aimed at educating the community about mental illness causes thereby reducing stigmatization and promote societal interactions with families caring for persons with mental illnesses. Mental illness is greatly associated with societal stigmatization. In the sub-Saharan Africa and probably in Africa as a whole, the stigma attached to mental illness is deeply rooted in cultural beliefs, where mental illness is associated with witchcraft. Not only that mental illness is a witchcraft illness, but there is also societal stigmatization of those who are mentally ill and their families [7-9]. Worse more, social relationships with neighbours and society at large are disturbed, and the same stigmatizations has resulted in strained relationships within some families themselves because some family members do not like to be associated with a mentally ill relative- all because of stigmatization. In some instances, the stigma attached to mental illness has led to delay in medical treatment seeking and consequently to a poor quality of life [4,10,11].

3) Soliciting policy makers and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to assist the families with monthly social/financial grants to support in the provision of both material, financial and basic needs of these patients. Caring for the mentally ill patient is no doubt a financial burden. Treatment cost is also a major financial challenge, of which families can be affected in various degrees- some mildly, moderately or severely, depending on the income and availability of funds of a particular family [9,16]. In our African settings, family members usually have to bear the costs for medications as well as hospital transport costs, without reimbursement [18,19]. On the other hand, most of African governments spent only less than one percent (1%) of the health budget on Mental Health Services [23]. This insufficient financing as well as low prioritization has led to the lack of mental health services provision at the primary level as well as failure of mental health outreach programs to kick off, thus making utilization of mental health care to begin at secondary level [24].

According to Brink, Van de Wart and Van Rensburg (2012) [13], limitations to the study refers to drawbacks

and restrictions that the researcher might encounter during the study. So, for this study:

4) that the population might not be adequate in terms of representation, given that not all mentally ill patients are referred to the psychiatric clinic at University Teaching Hospital,

5) time might not be adequate as the researcher had to divide the time to be used to conduct the study with other course responsibilities allocated to be done in the same time frame [43-72].

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!