Biography

Interests

Boshra Arnout, A.1, Ahed Alkhatib, J.2,3* & Khalid Jasim, J.4

1Department of Psychology, King Khalid University, Zagazig University, Egypt

2Department of Legal Medicine, Toxicology of Forensic Science and Toxicology, School of Medicine, Jordan University

of Science and Technology, Jordan

3International Mariinskaya Academy, Department of Medicine and Critical Care, Department of Philosophy,

Academician Secretary of Department of Sociology, Egypt

4Department of Educational and Psychological Science, College of Education, Ibn Rushd for Human Science, Iraq

*Correspondence to: Dr. Ahed Alkhatib, J., Department of Legal Medicine, Toxicology of Forensic Science and Toxicology, School of Medicine, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Jordan & International Mariinskaya Academy, department of medicine and critical care, department of philosophy, Academician secretary of department of Sociology, Egypt.

Copyright © 2019 Dr. Ahed Alkhatib, J., et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

There is evidence that interventions based on practicing gratitude may enhance subjective wellbeing. This study investigated the effect of a gratitude intervention on psychological well-being among a sample of females breast cancer patients in Saudi Arabia Kingdom (N=60). Researchers applied a scale of psychological well-being (PWB) and a scale of gratitude and the counseling program based on gratitude. Participants were measured at three points in time: before the intervention, immediately after the termination of intervention (week4), and at follow-up after one month. The results revealed that the gratitude intervention enhanced psychological well-being in participants, and this positive effect of practicing gratitude on psychological well-being persisted over one month. Theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed.

Introduction

In past, psychologists focused on ameliorating human sufferings such as depression, suicidal ideation, and

schizophrenia until the 20th century. There is a shift in mental health practice and research that emphasize

on positive human functioning and psychological well-being [1]. Positive psychology is used in literature

as an umbrella term for studying positive emotions, positive character traits, and positive institutions [1].

Interventions can be developed to decrease misery and build the enabling conditions of life [2].

Recently Cancer is one of the most prevalent diseases in the world generally and in the Arab world in particular, and is considered among the so-called (Diseases of the current age). As cancer is one of the causes of death; thus when a person knows that he or she has this disease, this causes many psychological and behavioral problems and reduces the enjoyment of life and well-being.

There is no doubt that the incidence of cancer is one of the most serious chronic diseases, which has attracted the interest of many researchers in the field of psychology of the effects and consequences of this disease on the patient mental health. Over the last few years, the risk of chronic diseases has increased, as it threatens the lives of individuals and peoples by causing physical and moral harm to the lives of the sick and those who control them. This makes it difficult to live with them, making the issue of health not only medical. Psychologists seek to know the role of behavior in the health of the patient for healthy lifestyles that alleviate the surrounding conditions, whether social, professional or psychological. Cancer is one of the leading causes of death worldwide, and statistics show that (2008) of the total deaths (13%) of people (7.9%) cancer caused deaths. Recent studies have also shown the spread of the disease in developing countries more. Cancer is a general term that includes a range of diseases, which can infect all parts of the body and is also referred to as malignancies. Cancer is a global problem. In 2010, it has affected more than eight million people worldwide, and WHO data indicate that more than two-thirds of these new cases and cancer deaths will occur in the third world countries, where disease rates remain increased. Many studies in this field have shown that there are many physiological and psychological changes when patients are directed to take chemotherapy or combination therapy (surgical, loss, chemotherapy) or radiotherapy. They have problems in social communication [3], low quality of life [4], mistrust and high pressure [5].

The study of Tho and Ang (2016) [6] aimed to synthesize the effectiveness of patient navigation programs for adult cancer patients undergoing treatment: a systematic review. Four studies (two randomized controlled trials and two quasi-experimental studies) with a total of 667 participants were included in the review. The results demonstrated no statistically significant difference in the quality of life of patients with cancer who had undergone patient navigation programs (pooled weighted difference = 0.41 [95% CI = -2.89 to 3.71], P=0.81). However, the two included studies that assessed patient satisfaction as an outcome measure both showed statistically significant improvements (p-values = 0.03 and 0.001, respectively). In the study that assessed patient distress level, there was no statistically significant difference found between the: nurse-led navigation and non-navigation groups (P = 0.675).

Psychological Well-Being

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared mental health as a state of wellbeing in which the

individual recognizes his or her own strengths, can deal with daily stressors, able to work efficiently, and

is capable to contribute to his or her community [7]. Various modes of positive psychology interventions

were developed to build character strengths that contain desirable traits (e.g. gratitude, hope, self-control

and etc.). These traits were derived from virtues extolled by ancient scholars and has been associated with

increased well-being [8]. Subjective well-being (SWB) is the personal perception and experience of positive

and negative emotional responses and global (domain) specific cognitive evaluations of satisfaction with

life. It has been defined as “a person’s cognitive and affective evaluations of his or her life” [9]. Eudemonic

happiness is necessary for positive psychological functioning; wellbeing may be associated with combination

of hedonia and eudemonia” [10].

Positive Psychological Interventions

Positive psychology is defined as interventions are treatment methods or intentional activities that aim to

cultivate positive feelings, behaviors, or cognitions [11]. According to Seligman (2002) [12], treatment is

not just fixing what is wrong; it is also building what is right. Fordyce’s (1977) [13] pointed to happiness

intervention, while Fava’s (1999) [14] pointed to well-being. Gratitude Interventions 165 therapy, and Frisch’s

(2006) [15] quality-of-life therapy, the positive psychotherapy approach of Seligman and his colleagues [16]

is particularly noteworthy in that it is directly and primarily based on building positive emotions, character

strengths, and meaning.

Although gratitude interventions might be regarded as a more recent addition to the traditional psychotherapy approaches, the central position occupied by the discussion on gratitude in philosophical and theological theories testifies to the importance of the notion throughout history [17].

Gratitude practice can be a catalyzing and relational healing force, whether in terms of enhancing mental health or preventing mental illness, gratitude is one of life’s most vitalizing ingredients. Clinical trials indicate that the practice of gratitude can have dramatic and lasting positive effects in a person’s life [18]. Peterson and Seligman (2004) [8] have developed the Classification of 6 Virtues and 24 Character Strengths to describe virtues and strengths that enable people to thrive. Every virtue, such as courage, humanity, justice, temperance, transcendence, and wisdom, consists of four specific character strengths. These character strengths include gratitude, forgiveness, open-mindedness, creativity, and kindness [8].

However, studies examining the effectiveness of positive psychology interventions have shown mixed results. Some researchers have found that positive psychotherapy notably boosted well-being and decreased depressive symptoms in participants (e.g., [16,19]). Other studies examining positive psychological interventions have found positive effects of practicing some character strengths such as gratitude, forgiveness, and mindfulness on SWB (e.g., [20-22]). In contrast, some studies have not found practicing PPIs to be advantageous overall, in comparison to control or placebo groups (e.g., [23,24]).

The Meaning of Gratitude

The word “gratitude” is derived from the Latin “gratia” which entails meanings of grace, gratefulness, and graciousness [8]. The conceptualization and theorizing of gratitude from a more psychological perspective has attracted attention only in recent years [25-28].

Gratefulness given interpersonally can be described as a willingness to acknowledge a valuable outcome received from another person’s kindness. There is also recognition that the other person purposely provided this benefit, usually at some individual cost [29]. Gratitude has a dual meaning: a worldly one and a transcendent one. In its worldly sense, gratitude is a feeling that occurs in interpersonal exchanges when one person acknowledges receiving a valuable benefit from another [18]. Feelings of gratitude are anchored in two essential pieces of information processed by an individual: (a) an affirming of goodness or “good things” in one’s life and (b) the recognition. Gratitude has been conceptualized in literature at both state and trait (disposition) levels [30,31]. As a state, Chan (2010) [21] defined gratitude as” a subjective feeling of wonder and appreciation for outcomes received, but as a trait, gratitude is an individual predisposition to experience the state of gratitude in life.

McCullough et al (2001) [32] defined gratitude as a moral affect, that is, an affect with moral precursors and consequences. They suggested that the person, in experiencing gratitude, is motivated to engage in prosocial behaviors, becomes energized to sustain prosocial behaviors, and is inhibited from performing destructive interpersonal behaviors. McCullough, Emmons, and Tsang (2002) [33] distinguished four facets of grateful disposition: intensity, frequency, span, and density. Gratitude also has been defined in the literature as an emotion, a moral virtue, an attitude, a personality trait, and a coping style [34]. Gratitude is the expression of appreciation for what is valuable and meaningful to the self [35].

Subjective well -being (SWB) is often described in literature as a construct consisting of both cognitive and affective components [36]. The cognitive component involves a person’s judgments of his or her satisfaction with life. These judgements may be general or may involve specific areas of this person’s life (e.g. satisfaction with education, or marital satisfaction). On the other hand, the affective component consists of a person’s positive and negative emotions. Grateful individuals perceive their existence as a gift, and they often feel more satisfaction than deprivation in life [29]. Watkins et al (2003) [31] conceptualized dispositional gratitude differently as a combination of four distinct characteristics: acknowledgment of the importance of expressing and experiencing gratitude, lack of resentment (feelings of a sense of abundance rather than deprivation), appreciation for the contributions of others, and appreciation for simple pleasures. Adler and Fagley (2005) [37] chose to focus broadly on appreciation in terms of eight dimensions: appreciation of people, possessions, the present moment, rituals, the feeling of awe, social comparisons, existential concerns, and gratitude behaviors.

Gratitude Interventions and Well-Being

McCullough (2003) [30] found that gratitude has many benefits. These include psychological, such as increased positive affect, attentiveness, more energy, and enthusiasm; physical, such as fewer illnesses, better sleep, and increased exercise and interpersonal benefits, such as feeling less lonely and more connected. The sources of this goodness lie at least partially outside the self. It is a natural emotional reaction and quite likely a universal tendency to respond positively to another’s benevolence, or at least in violation of the law of reciprocity, not responding to kindness with harm. There is a potent, vitalizing energy that accompanies both the affirmation and recognition components of gratitude and helps account for its transformational healing power in human functioning [18].

Nelson (2009) [38] mentioned that gratitude influence wellbeing either directly as a causal factor, or indirectly by as buffering factor of negative states and emotions. Gratitude interventions can be used with youth to increasing wellbeing even in adversity state [30]. Recently, Chan (2010) [21] investigated the effects of a gratitude intervention on job burnout and psychological well-being in Chinese teachers. Results showed that gratitude interventions once a week for the period of eight weeks increased SWB (positive affect and life satisfaction). Lau and Cheung (2011) [39] in a study used a task on writing about gratitude inducing events, about hassles, and providing neutral descriptions of life, results referred that the gratitude interventions reduced death anxiety more than the hassle.

Killen and Macaskill (2015) [40] study examined the impact of keeping a gratitude diary on the wellbeing and stress levels of adults over the age of 60 and found significant positive differences in both indicators. Gratitude protects individuals from stress and depression even allowing for personality factors [41]. By decreased stress and develop personal resources such as resilience, gratitude interventions can increase psychological well-being [42]. If person express gratitude to others, this can increasing life satisfaction and strength of personality traits [23]. And also through schematic processing gratitude can increase psychological well-being, grateful person has specific schematic which may lead to more gratitude after given help [41].

Several interventions have been developed to foster gratitude in individuals, include writing gratitude letters or keeping gratitude journals [1,21,30]. Focusing on things that we are grateful for helps people to experience greater life satisfaction and more positive emotions, while building on human strengths, such as gratitude and optimism [43]. The possibilities of gratitude within clinical contexts can be viewed within the framework of accelerated experiential dynamic therapy (Russell and Fosha, 2008). Gratitude arises within other aspects of the therapeutic relationship. Consider gift giving, the act of giving and receiving a gift can be fraught with a widely divergent assortment of perceptions, psychological states, and conflicting emotions. Grateful people experience higher levels of positive emotions such as joy, enthusiasm, love, happiness, and optimism, and gratitude as a discipline protects us from the destructive impulses of envy, resentment, greed, and bitterness. People who experience gratitude can cope more effectively with everyday stress, show increased resilience in the face of trauma-induced stress, recover more quickly from illness, and enjoy more robust physical health [44]. Taken together, these results indicate that gratitude is incompatible with negative emotions and pathological conditions and that it may even offer protection against psychiatric disorders [18]. This intervention aims to encourage people to truly demonstrate the feeling of thankfulness for received goods [45].

Miller (1995) [46] proposed a cognitive-behavioral approach that enables people to learn gratitude through completing four steps: (a) identifying non-grateful thoughts; (b) creating gratitude-supporting thoughts; (c) replacing the non-grateful feelings with the gratitude-supporting feelings; (d) and converting the inner feelings into action.in this study, the program was planned based on this approach. However, Sansone and Sansone (2010) [35] suggested a number of strategies which may enhance feelings of gratitude and here are three you can try. Choose one what feels best for you-or all three. Then implement as a daily practice: (a) Journaling (e.g. writing down three things daily for which you are grateful), (b) Writing/sending a gratitude note or letter for someone, (c) Meditating on gratitude.

Brief counseling has emerged as a result of the rapid race and stress of life in the 21st century that increasing problems of all life. The brief counseling is applied individually or in groups. It involves training in real behavior and related with the individual’s immediate experience in order to achieve personal growth. This is to ensure that the client receives the greatest instructional benefit in the shortest possible time. It is based on the psycho-educational model or the “instructional training” model and counselor is seen as a “psychologist or teacher of skills” and focuses on developing one-by-one skills. And it is based on the assumption that the problems suffered by the client in his or her life are due to mismanagement and the use of wrong and inappropriate methods to solve them, and therefore the brief counseling depends on new methods that differ from those of the traditional one, While adhering to ethics principles, and to allow the individual to express his feelings [47].

Based on previous researches results, cancer patients are cope with increasing stressful events that reduced their ability to cope, thus increasing gratitude of them may be a useful intervention for their health.

In summary, recent theorizing and research studies have expanded our understanding of the role that gratitude could play in providing a viable treatment option in the caring of cancer patients. A goal of the present research is to examine whether a specific positive psychology intervention, a gratitude intervention, is effective in increasing psychological well-being outcomes.

Research Aims

The primary aims were:

1. To examine whether a gratitude intervention can increase psychological well-being on Saudi cancer

patients.

2. To explore whether the effect of a gratitude intervention on psychological well-being persists over time.

Research Hypotheses

It was hypothesized that:

1. The cancer patients who received the gratitude promotion program would have higher gratitude and

psychological well-being scores than the patients who did not receive it.

2. There are statistically significant differences between pre measures and post measures of gratitude and

psychological well-being among cancer patients who received the gratitude promotion program in the favor

of post measures.

3. The positive effect of the gratitude intervention on SWB would persist over a period of one month.

Methodology

The researchers used the experimental method, and the design used is the study is based on the division of

the sample into two experimental and control groups, using the pre-test and post-test and follow-up test.

Informed consents were obtained from all participants after explanation of the treatment procedures, and

research protocol.

Sixty female participants were recruited, whose ages ranged from 41-58 years. participants were with breast

cancer disease among outpatients in Asir Hospital in Saudi Arabia Kingdom. The researchers chose this

sample according to certain characteristics, including gender, where all respondents were females, with

secondary education level and were married, as was the economic situation of the average income. After

checking the availability of the previous conditions and checking the homogeneity of the sample and

the equivalence in the variables and the pre-test of the level of psychological well-being, the sample was

randomly assigned to two groups, each group consisting of (30) patients. Within the experimental group,

participants were 48.27±4.5 years old, and within the control group, participants were 47.17±4.18 years

old. For homogeneity testing in accordance in both the age variable (t=0.981, P =0.331, p<0.05) and the

dependent variable gratitude before application of program (t=0.894, P =0.375, p<0.05), and in psychological

well-being (t=0.242, P =0.809, p<0.05) using the t-test for two independent groups, of the experimental and

control groups, results showed that both groups were homogeneous.

Materials

All materials used in this study were self-report measures, participants completed the following measures:

The Demographic Questionnaire included the following information about each participant: sex, type of

disease, duration of disease, level of income, social status and number of children in order to equivalence

between the experimental and control groups.

Researchers translate the GQ-6 is a short, self-report measure of the disposition to experience

gratitude (McCullough, Emmons and Tsang, 2002). Participants answer 6 items on a 1 to 7 scale (1 = “strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”). Higher scores indicate greater dispositional gratitude. Two

items are reverse-scored to inhibit response bias. The GQ-6 has good internal reliability, with alphas between

0.82 and 0.87, and there is evidence that the GQ-6 is positively related to optimism, life satisfaction,

hope, spirituality and religiousness, forgiveness, empathy and prosocial behavior, and negatively related to

depression, anxiety, materialism and envy. The GQ-6 takes less than 5 minutes to complete, but there is no

time limit [33]. The gratitude scale has acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.85), in this study.

Twenty-item scale measures psychological wellbeing with a three-point Likert scale from 1(rarley) to 3

(much). The psychological well-being scale has good psychometric properties, the results of reliability and

validity showed that the correlation coefficients of the scale’s items scores with the total score of the scale

were statistically significant at (p< 0.01), ranging from 0.450 to 0.762. (p < 0.01). Alpha-Cronbach’s stability

coefficients for the psychological well-being scale (0.824). In this study Cronbach alpha here was 0.89.

The results of reliability and validity showed that the correlation coefficients of the scale’s items scores with the total score of the scale were statistically significant at (p< 0.01), ranging from 0.450 to 0.762. (p< 0.01). Cronbach alpha for the psychological well-being scale was (0.824).

Only participants who completed the whole study were included in data analysis. Ethical approval was

obtained from the participants and from Asir hospital administration. The current study’s objective was

explained to all participating patients. The patients of experimental group were asked if they intended

to continue with the intervention at the end of the intervention. All patients had been diagnosed with

cancer and were undergoing radiotherapy. They had received a cancer diagnosis between 2 years and 3

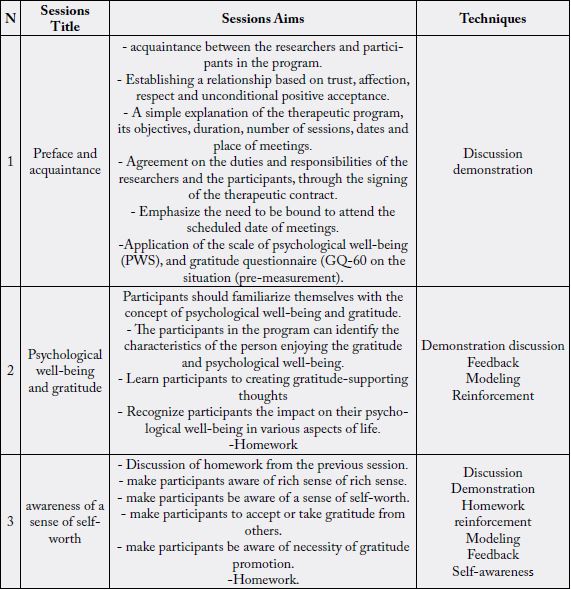

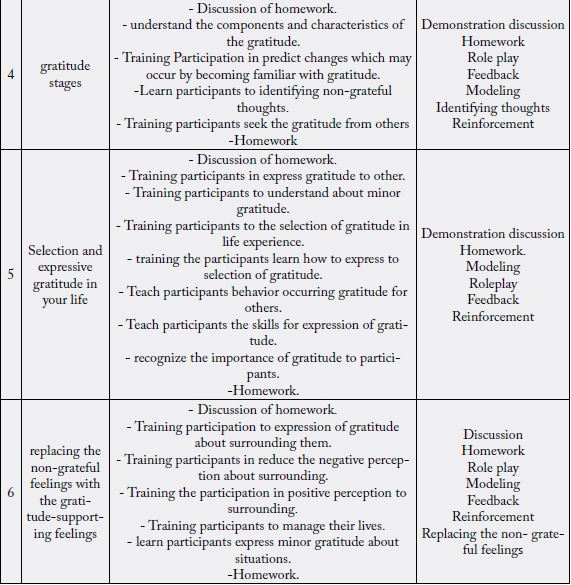

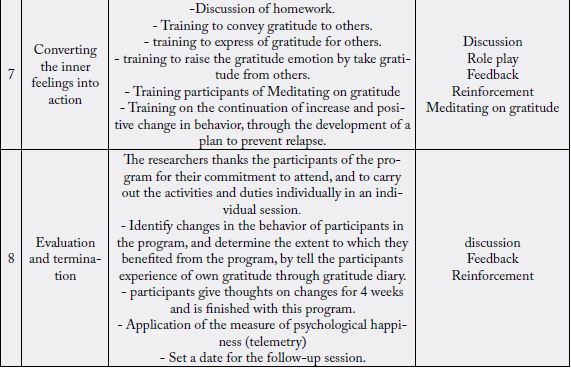

years prior to participation in this study. The program, which has been designed for eight (8) sessions, has

been implemented over a month of two sessions peer week, and the duration of the session an hour, and

began to apply the program from 28/8/2018 to 27/9/2018 (table 1). The experimental treatment of this

study was the newly developed gratitude program for 4 weeks to increase psychological well-being among

cancer patients, about 45 min for a total of eight sessions. Researchers used methods such as discussion,

demonstration, reinforcement, feedback, self-awareness, identifying thoughts, meditating on gratitude, roleplaying,

replacing the non- grateful feelings and giving homework about writing a gratitude diary.

Data Collection

The psychological well-being and gratitude Questionnaire were applied to the participants in the experimental

group, and that was in 28/8/2018.

Through the application of the psychological well-being and gratitude Questionnaire on the members of the

experimental group, and that was in 28/8/2018.

During the implementation of the program and during the sessions of the intervention, where do not move

from one activity to another only after confirmation of the participants mastery of the previous activity. Each

session was evaluated after completion to ensure the achievement of the objectives of the session, through

feedback and observing the change in the behavior of the participants.

This was done at the last session of the program after finishing directly from the application of all the sessions

of the intervention using the program evaluation form, as well as through the application of the post by applying psychological well-being scale and gratitude questionnaire to the members of the experimental

group, and that was in 27/9/2018.

The follow-up measurement session was scheduled for 28/10/2018, where gratitude questionnaire and psychological

well-being were applied to experimental group participants after one month from the date of

completion of the application to ensure the continuous increase and verify the persist of the effectiveness of

the program.

Data Analysis

Preliminary data analyses included descriptive statistics for demographic data, psychological well-being and

gratitude scores. The dataset was screened for normality, the results of normality indicated that there were

no outliers but there was a tendency towards normality. The dependent variables were gratitude and psychological

well-being, the independent variables were completion of counseling program and the measures

were repeated at three times points. Mean differences were computed on all the variables where there were

significant differences across time.

Results

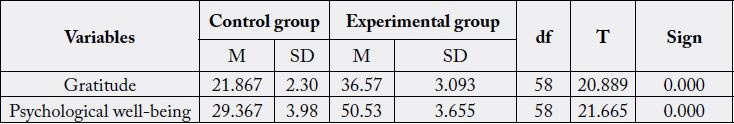

“The cancer patients who received the gratitude promotion program would have higher gratitude and

psychological well-being scores than the patients who didn’t received it” was supported as it showed

statistically significant difference between the two groups in post measures (Table 2).

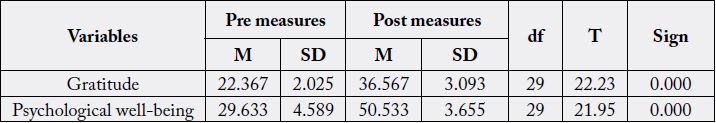

“There are statistically significant differences between pre measures and post measures of gratitude and

psychological well-being among cancer patients who received the gratitude promotion program in the favor

of post measures” was supported as it showed statistically significant difference (Table 3).

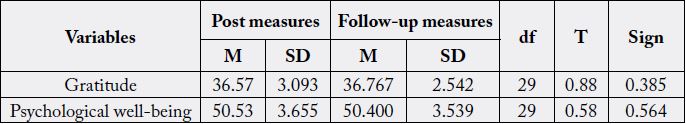

“The positive effect of the gratitude intervention on SWB would persist over a period of one month”. The

results showed that there was no statistically significant difference between Post-intervention Assessment

and Follow-up Assessment on Measures of gratitude (T = 0.881, P = 0.385), and psychological well-being

(T= 0.583, P= 0.564) (Table 4).

Discussion

Gratitude promotion program of this study appeared to be effective in promoting gratitude disposition

and improving psychological well-being in the experimental group (P < 0.05). This result was similar to

the study of Emmons and McCullough (2003) [30] in which college students were more optimistic about

their life and had an increased sense of subjective well-being by recording five gratitude events once a

week. A similar result was also found in the study of Kim (2008) [49] in which high school students’ life

satisfaction and positive affection increased by completion of a gratitude program; and the study result of

Jo et al., (2008) [50] that improved gratitude disposition and increased life satisfaction in the general adults

through writing a gratitude journal. And these results were similar to the results of Chan (2010) [21] study

that found the 8-week gratitude intervention program contributed to increased feeling of gratefulness in

Chinese teachers, and with the study of Killen and Macaskill (2015) [40] that found gratitude interventions

enhanced psychological well-being in older adults. This effectiveness is due to the gratitude is associated with

an appreciation of other individuals or things that are usually overlooked in day-to-day life. Being thankful

for large or small things that other people have done for us is a way to increase the gratitude felt in one’s

life [27]. Evidence showed that the effects of gratitude practice can be classified as the following categories:

Increase in happiness and life satisfaction; effective coping with adversity; strengthen social bonds; benefits

health; and broaden the civic, moral, and spiritual dimensions [51].

As shown by Gordon et al (2004) [52], importance of learning and practice was related to the resource of gratitude in one’s life. This result differed from the report of Seligman, Steen, and Peterson (2005) [1], in which five interventions including writing the gratitude letter using internet reduced the depressive level. Furthermore, Kim and Yi (2009) [53] determined that gratitude awareness reduced depressive score effectively in college students by writing gratitude event and gratitude letter [54-58].

Conclusion

In this study, a gratitude disposition promotion program was developed for promoting gratitude disposition

of cancer patients in Saudi Arabian and verified its effect. The study results indicated that gratitude disposition

promotion program was a useful intervention to raise the gratitude disposition and psychological well-being

of cancer patients in community. This program could contribute to the expansion of cancer research area and

reaffirms that a practical application is easy, and the utilization is high effect, from the practical point of view.

Conflict of Interest

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!