Biography

Interests

Yoon Hang John Kim1*, Wendy Luo1 & Kirsten West2

1Integrative Health Program, Department of Family Medicine, University of Kansas Medical School, Kansas City, Kansas

2Naturemed Integrative Medicine, Boulder, Colorado

*Correspondence to: Dr. Yoon Hang John Kim, Integrative Health Program, Department of Family Medicine, University of Kansas Medical School, Kansas City, Kansas.

Copyright © 2019 Dr. Yoon Hang John Kim, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recently endorsed the use of integrative medicine in the management of breast cancer patients as proposed by the Society of Integrative Oncology (SIO). The SIO clinical guideline provides evidence-based recommendations for the use of integrative medicine during and after conventional therapies. SIO clinical practice guideline was against any use of ingested dietary supplements to manage breast cancer treatment-related adverse effects. However, in Japan, Korea, and China, there is a long history of using Chinese herbs in cancer patients with increasing evidence documenting of potential benefits. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to provide a pragmatic, evidenced based clinical guideline on how to safely use Chinese herbs in cancer patients undergoing conventional care.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recently endorsed the use of integrative medicine in the management of breast cancer patients as proposed by the Society of Integrative Oncology (SIO) [1]. The SIO clinical guideline provides evidence-based recommendations for the use of integrative medicine during and after conventional therapies. Key positive recommendations include the use of specific modalities in the management of common conditions listed below:

• Anxiety/Stress Reduction: Music therapy, meditation, stress management, and yoga

• Quality of Life Improvement: Meditation, yoga, massage, and music therapy

• Reducing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: Acupuncture

However, SIO clinical practice guideline was against any use of ingested dietary supplements to manage breast cancer treatment-related adverse effects. This guideline is not observed in practice, as more than 60% of cancer patients may be taking supplements during active treatment for cancer [2]. Furthermore, it is concerning that patients do not seek advice on supplements from their conventional, integrative, or alternative medical practitioner.

Of many types of supplements, Chinese herbal supplements may pose the greatest challenge; these supplements typically consist of multiple herbs. Subsequently, the risk to benefit analysis becomes more difficult to assess. Nonetheless, the use of Chinese herbs in China, Korea, and Japan for cancer is well documented and socially well accepted. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to provide a pragmatic, evidenced based clinical guideline on how to safely use Chinese herbs in cancer patients undergoing conventional care.

Chinese Medicine

Chinese medicine has developed from Taoist observation of nature. Some of the ideas include duality of state

which may be translated as sympathetic and parasympathetic and the concept of harmony may correlate with

the homeostasis. However, a key area of difference between Chinese medicine and conventional medicine

is the notion of Qi or energy which has not yet been characterized through scientific means but remain

central to Chinese medicine construct [3]. The notion of Qi or energy exists in all four domains of Chinese

medicine. These four main branches of Chinese medicine are described below:

Acupuncture is a form of medical treatment that involves inserting needles (sterile, single use needles are the

standard of care in the U.S.) at specific sites of the body. The technique originated in China more than 2,000

years ago and continues to be practiced throughout the world [4]. According to Chinese medicine paradigm,

meridians serve as channels for energy referred as “qi” throughout the body. It is thought that inserting

needles and stimulating (manual, heat, or electricity) acupuncture points can result in restoring homeostasis.

More modern explanations of acupuncture include neurotransmitter theory, gate theory, endorphin theory,

and more recently anti-inflammatory theory [5].

Qi Gong is a type of physical exercise that combines the use of breath, movement, and intention to guide the

flow of Qi. Postures are often based on the movement of animals. Tai Chi is a specialized form of Qi Gong

and is also practiced for self-defense applications which include push hands and weapons training. The practice of medical Qi Gong can be achieved through a patient’s self-practice (also referred as internal Qi

Gong) or can be practiced by a medical Qi Gong expert as a means to give and direct Qi to promote a

patient’s well-being (also referred as external Qi Gong) [6].

Tuina is a type of manual therapy that involves massage and acupressure. Tuina means “to push and lift.”

Using the hands, the practitioner follows the course of meridians and often employ techniques that involve

brushing, stroking, kneading, and rubbing the skin, muscles and joints of the body. Tuina is best suited for

those with musculoskeletal conditions, chronic pain, and stress related conditions [7,8]. Due to the fact that

the entire body is manipulated, people often report an overall sense of wellbeing and whole body physical

improvement.

Herbs are a vital component of traditional Chinese medicine. There are more than 100,000 medicinal

combinations recorded in literature and there are over 10,000 individual herbs [9]. In the practice of Chinese

herbal medicine, it is not uncommon for a given practitioner to frequently modify an herbal combination to

match a patient’s changing condition and needs. Furthermore, rarely is only one herb used as it is believed

that a combination of herbs balances therapeutic actions - i.e., any one given herb may best be balanced with

another to reduce its toxicity. The presence of multiple herbs confounds as to the active ingredients and make

studying Chinese herbal medicine more difficult.

Evidence Based Use of Chinese Medicine in Cancer Patients

In 2007, Lee et al published a systematic review of controlled clinical trials for Qi Gong in the treatment

of cancer. It was concluded that evidence was lacking and that more studies were needed [10]. A second

article, also published by Lee et al, concluded that there was a lack of evidence for the use of Tai Chi as an

adjunctive treatment in cancer care [11]. However, there have been more recent randomized controlled trials

documenting the beneficial role of Qi Gong for improving quality of life in women undergoing radiotherapy

for breast cancer [12]. In addition, another review paper confirmed the positive effects of Qi Gong on

improving quality of life measures in cancer patients [13]. In 2018, Wayne et al published a systematic

review and meta-analysis on using Tai chi and Qi Gong for cancer-related symptoms and quality of life [14].

The authors also concluded Tai Chi and Qi Gong show promise in addressing cancer-related symptoms and

improving quality of life measures in cancer survivors.

In 2008, Lu et al published a review article on the value of acupuncture in cancer care [15]. Per this study, the

authors concluded that acupuncture may provide clinical benefit for cancer patients with treatment-related

side effects. The primary side effects showing benefit included nausea and vomiting, post-operative pain, cancer related pain, chemotherapy-induced leukopenia, post chemotherapy fatigue, and xerostomia.

Additional side effects that were mitigated, although less strongly were: insomnia, anxiety and quality of

life (QOL). In 2017, Chiu et al published a systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the effects

of acupuncture on malignancy related, chemotherapy or radiation therapy induced, surgery-induced, and

hormone therapy induced pain [16]. Authors found that acupuncture was effective in relieving cancer

related pain, particularly pain related to malignancy and surgery. However, several systematic reviews on the

use of acupuncture for treating cancer-related fatigue showed inconclusive effect. The latter may have been

due to the lack of high quality randomized controlled trials [17-20]. In 2018, O’Sullivan and Higginson

published a systematic review on the effectiveness of acupuncture for treating radiation induced xerostomia

[21]. The authors concluded that acupuncture was beneficial for radiation induced xerostomia. Currently,

two phase III trials are being conducted; one study is exploring the effectiveness of acupuncture for treating

xerostomia, while the second study is exploring the effectiveness of acupuncture for preventing xerostomia

during radiation treatment.

To this date, there is no systematic review on the use of Tuina in cancer patients. However, there is review

paper, published by Kong et al, that evaluated the use of Tuina for patients with low back pain. These authors

concluded that Tuina may be effective for patients with low back pain [22]. These authors also noted that

many of these trials suffer from poor methodological quality.

The SIO practice guideline concluded against the use of ingested dietary supplements to manage breast

cancer treatment-related adverse effects. Chinese herbs fall into this category. However, in China, Korea,

and Japan, Chinese herbs are widely used in the care of cancer patients before, during and after treatment.

Additionally, some chemotherapeutic agents are derived from Chinese herbs. Examples of plant-derived

chemotherapeutic agents include but are not limited to: Vinca alkaloids, taxanes, and camptothecins [23].

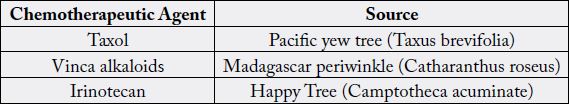

The table below summarizes chemotherapeutic agents that are from plant sources: [23]

Importantly, in recent years, ingredients proving to act as chemotherapeutic agents have been discovered. These include: artesunate, homoharringtonine, and arsenic trioxide. These ingredients have been used in Chinese medicine [24]. Table 2 summarizes chemotherapeutic agents originating from Chinese medicine.

There are currently two systematic reviews on the use Chinese herbs as an adjunctive therapy in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer [29,30]. These reviews conclude that there is a lack of large-scale randomized clinical trials and consequently, a need for more studies. However, Li et al concluded that the use of Chinese herbs offered a significant improvement in patient functionality as measured by Karnofsky performance score. Chen et al concluded similarly; quality of life was improved when Chinese herbs were employed as an adjunctive therapy to chemotherapy [31].

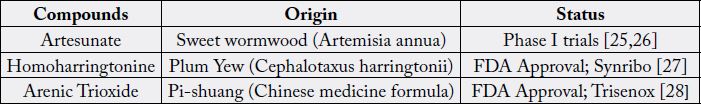

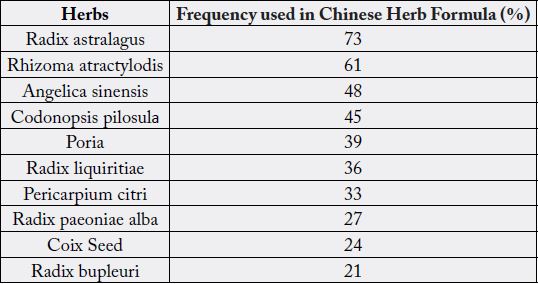

As stated in the earlier section, one of the challenges in evaluating Chinese herbal supplementation lies in that Chinese herbal formulas consist of more than one herb. Li et al sought to offer a solution to this dilemma by tallying the Chinese herbs used most frequently in the clinical trials [31]. This is illustrated in the following table:

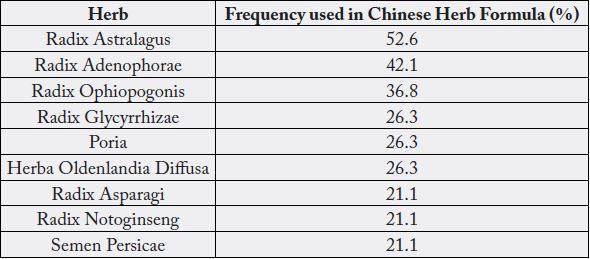

As can be seen, astralagus was the most frequently included herb in the Chinese herbal formulas in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancers. Subsequently, MuCulloch et al published a meta-analysis on combining astralagus-based Chinese herb formula and platinum-based chemotherapy for treating advanced non-small-cell lung cancer [32]. The authors concluded that astralagus-based Chinese herbs may increase effectiveness of platinum-based chemotherapy when combined with chemotherapy. These results and potential benefits are summarized in the table below:

In 2016, two systematic reviews evaluating the use of Chinese herbs as an adjunctive therapy for breast cancer

were published [33,34]. Both studies concluded that there is a lack of high quality trials and future largescale

randomized controlled trials are needed. These trials would enable elucidation of how specific Chinese

herbs and formulas effect breast cancer patients during treatment with a primary endpoint being safety.

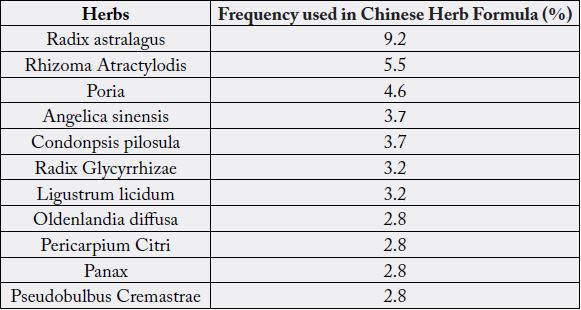

The most commonly utilized herbs in the treatment of breast cancer patients with and without traditional

pharmaceutical based therapies are listed in the two tables below. These were compiled in the 2016 reviews.

Below is a list of Chinese herbs commonly used in the treatment of breast cancer by Sun et al [33].

Similar to those reviews on Chinese herbal therapies and lung cancer, both systematic reviews found that astralagus was the most commonly used herb in Chinese herbal formulas.

The use of Ginseng during chemotherapy has been evaluated in several studies to date. Its safety and efficacy

in the treatment of cancer (whether as a treatment or as an adjunct to conventional therapies) is important,

as Ginseng Is used worldwide and is especially popular as a single herb in South Korea [35]. A review by

Chen et al review established that Ginseng, when used in combination with some chemotherapeutic agents,

may enhance the anti-tumor effect [35]. The summarized studies were largely in vitro and in vivo (animal)

and not in clinical trials. Due to this fact, the authors concluded that there is insufficient clinical evidence

to warrant its use as an adjunct to chemotherapy at this time. A second study, by Chong-Zhi et al, also

published a review of in-vitro research findings demonstrating possible enhanced anti-cancer effects with

the use of red ginseng or heat-processed ginseng [36]. Finally, a retrospective study was performed by Cui et

al studying the association of ginseng use with survival and quality of life among breast cancer patients [37].

Here, the authors concluded that compared with patients who never used ginseng, regular users of ginseng

had a reduced risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio associated with ginseng users were 0.17; 95% confidence

interval 0.52 to 0.98). These authors also concluded that the use of ginseng in cancer patients was associated

with improved quality of life scores.

Traditional Chinese medicine was first introduced into Japan between the 6th and 8th century and was

named Kampo. The meaning of Kampo literally means the Chinese way (of healing). In 1868, as a result of

the Meiji Restoration, many aspects of Japanese society modernized including its medical system focusing

on western medicine [38]. Consequently, the practice of Kampo declined [39]. Hoewever, after the second world war the interest in Kampo renewed. In 1967 six Kampo extracts were granted permission for medical

use and increased to 148 formulas in 2000. Today, Kampo is classified as a pharmaceutical and held to

pharmaceutical standards of production and quality control [40].

Japanese physicians are trained in conventional medicine and Kampo. This contrasts with China, Taiwan and Korea, countries which use a dual medical system consisting of western medically trained medical providers (MD) and Chinese medically trained OMD. Every Kampo formulation contains a standardized amount of each herbal extract and screened for contaminants. The specific formula used is based on a patient’s symptoms and abdominal diagnosis. Given this approach it has been difficult to conduct randomized clinical trials using Kampo. Despite these limitations, emerging research shows that Kampo is promising for improving the quality of life for cancer patients [41].

Although Western medicine excels in the diagnosis of cancer, the use of radiation, surgery and chemotherapy is not without side effects. Chemotherapy carries the disadvantage of damaging normal tissue in addition to cancer cells. Those cells that frequently undergo division is most affected which can result in diarrhea, hair loss, bone marrow suppression, and neuropathy. In Japan, Kampo is used as an adjunct to conventional cancer treatment as it helps alleviate chemotherapy side effects and bolsters innate immunity [42].

The development of Kampo formulations in cancer treatments is being guided by both traditional use

and evaluation by scientific reviews. For example, chemotherapy induced neuropathy results in significant

loss of quality of life. The following anti-cancer drugs has peripheral neuropathy as a known side effect:

taxane based drugs (paclitaxel, docetaxel), vinca alkaloids (vincristine sulfate) and platinum based drugs

(cisplatin and oxaliplatin) [43]. The Kampo formulations such as Hange-sahshin-to and goshajinkigan are

widely used in Japan for peripheral neuropathy symptoms. Clinical trials show that goshajinkigan may

prevent neuropathy in non-resectable or recurrent colon cancer patients treated with oxaliplatin [44]. Coadministration

of goshajinkigan with docetaxel has shown to revent neuropathy in breast cancer patients

[45]. However, a 2017 systemic review and meta-analysis by Kuriyama and Endo concluded that the current

evidence is low quality and insufficient; therefore, the authors stated that using goshajinkigan as a standard

of care is not recommended. This highlights the common motif in integrative medicine research - the need

for higher quality trials [46].

Irinotecan hydrochloride is an anticancer drug that inhibits nucleic acid synthesis via topoisomerase I

imbibition. The main side effects are leukopenia and diarrhea and a leading cause of drug discontinuation.

The kampo formulation Hange-shashin-to contains baicalin a beta glucuronidase inhibitor that appears to

alleviate Irinotecan induced diarrhea. A comparison trial showed improvements in diarrhea grades (severity)

as well as reduced frequency of diarrhea grades 3 and 4 [47]. The comparison was not double blind which

can lead to bias by participants and researchers.

While Kampo formulations may alleviate side effects of cancer therapy, it also may bolster innate immunity

and may improve patient survival. A retrospective review of 174 patients with cervical cancer treated with

radiotherapy and Kampo were compared with 231 patients treated without radiotherapy and Kampo during

the same period from 1978-1998 by Takegawa et al [42]. The patients treated with both therapies had

greater survival rates with uterine cervical cancer at all stages of disease.

The use of Juzen-taiho-to as post active treatment for cancer patients was reviewed by Yamakawa et al. in

2013 [48]. Juzen-taiho-to is one of most utilized Kampo formulas; as such, Haruki and Saiki published

a textbook on the scientific evaluation and clinical applications, and Borchets et al. published a review

paper focusing on the mechanism of Juzen-taiho-to. The paper mostly focusfocused on in vivo studies of

hepatoprotective effects on mice treated with chemotherapeutic agents [49,38]. Hochu-ekki-to is another

formulation used either in combination with or as an alternative to Juzen-taiho-to [50].

Table 7 summarizes evidence-based recommendations of Kampo formulas for clinical indications from the review of literature:

Ohno et al. published an article demonstrating that Rikkunshi-to suppresses cisplatin-induced anorexia

in humans [51]. Authors concluded that Rikkunshi-to appeared to prevent anorexia induced by cisplatin,

resulting in effective administration of chemotherapy with cisplatin - allowing patients to remain on schedule

for treatments. Another study showed that Rikkunshi-to improved chemotherapy-induced nausea and

vomiting in advanced esophageal cancer patients receiving Docetaxel/5-Flurouracil/Cisplatin treatments

[52]. Fujitsuka et al. published an article proposing Rikkunshi-to as a novel treatment of cancer cachexia

through the mechanism of ghrelin receptor mediated mechanism.

There is increasing evidence of Kampo formulations such as Juzen-taiho-to, Hochu-ekki-to, Kami-shoyosan-

to have hepatoprotective effects in vivo [53-55]. However, the protective effect of Sho-saido-to on liver

cirrhosis and carcinoma is best documented and widely accepted in Japan, Korea, and China [56].

While there is not yet a clinical trial of Kami-shoyo-san for cancer patients, because of its potential usefulness

and the heavy burden of suffering due to hot flashes and emotional distress among survivors of cancer,

Kami-shoyo-san has been added. Qin et al published the results of meta-analysis of randomized controlled

trial of Kami-shoyo-san (also known as Jia Wei Shao Yao San or Free and Easy Wanderer Plus) [57].

Results showed that Kami-shoyo-san may be an effective herbal formula in treating depressive symptoms. In

addition, Kami-shoyo-san, when added to conventional medications for treating depressive symptoms, the effectiveness appeared to be enhanced - demonstrating possible synergy. An interesting study was conducted

by Ushiroyama et al demonstrated increased plasma TNF-alpha levels in depressed menopausal patients

taking Kami-shoyo-san.

In addition to depression, Hidaka et al published the results of a clinical trial of hormone-replacementtherapy resistant patients experiencing climacteric syndrome and emotional distress [58]. The results showed that Kami-shoyo-san was effective in 73.3% (P<0.0001) for controlling vasomotor symptoms and in 77.8% for psychological symptoms (P<0.0001).

Discussion

To date, there exist many terms used to describe medicine that is outside the conventional scope of practice.

These include, but are not limited to, holistic medicine, alternative medicine, complementary medicine,

integrative medicine, and functional medicine. Semantics of these terms, particularly the terms alternative,

complementary, and integrative will be discussed.

Alternative medicine and complementary medicine follow different, and at times, opposing tenets. Alternative medicine rejects conventional medicine and focuses solely on alternative modalities of healing [61]. Whereas complementary and integrative medicine utilize alternative modalities of healing in addition to and alongside conventional approaches [61]. The Society of Integrative Oncology focuses on the latter approach by supporting the use of specific, evidence-based alternate modalities in conjunction with active treatment of cancer. These treatments may include surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy. These complementary modalities are meant to be supportive - not curative.

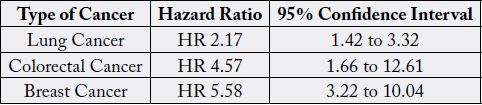

Two publications recently demonstrated the potential harm of dismissing conventional therapies in lieu of alternative methods in the treatment of cancer. In 2018, Johnson et al published an article titled “Use of Alternative Medicine for Cancer and Its Impact on Survival [62].” The authors identified 281 patients with non-metastatic breast, prostate, lung, and or colorectal cancer who chose alternative medicine as the sole cancer treatment. Disease outcomes were matched and compared to 560 patients who received conventional cancer treatment. The study outcomes demonstrated a greater risk of death in those who chose alternative medicine compared with those who underwent conventional cancer therapies (hazard ratio = 2.50, 95% confidence interval = 1.88 to 3.27). It was concluded that alternative medicine, without the use of conventional treatment, is associated with a greater risk of death. Furthermore, the hazards ratio was greatest for breast cancer. This was followed by colorectal cancer and then lung cancer. Prostate cancer did not result in an increased risk of death when only alternative medicine was used. These results may be due to the fact that the treatments for prostate cancer may increase morbidity and result in a significantly decreased quality of life. More studies are needed to confirm these findings. However, if alternative medicine provides no worse outcomes and saves patients from morbidity, it may be a preferred route for many patients. The study by Johnson et al shows that for the majority of cancers, this is not the case.

A follow-up article was published by Johnson et al titled “Complementary Medicine, Refusal of Conventional Cancer Therapy, and Survival Among Patients with Curable Cancers [63].” This retrospective observational study used data from the National Cancer Database on 1,901,815 cancer patients with 258 patients in the complementary medicine group and 1,901,557 patients in the control group. The authors found that patients who received complementary medicine were more likely to refuse additional conventional cancer therapy, and had a higher risk of death. Subsequent analysis attributed the higher risk of death to the refusal of additional conventional cancer therapies. The results from this study indicate that users of complementary medicine are more likely to refuse conventional therapies. This refusal was associated with a higher risk of death. This is a true issue, especially in cases where sustained remission and cure may be attainable.

It is well known that many patients now seek integrative oncology services. The primary purpose of integrative oncology should be to assist patients in rational decision-making in regards to cancer therapy while also respecting a patient’s choice. This must be done without compromising the outcome or diminishing a patient’s chance for overall survival. It follows that the practice of integrative oncology must include outcome analysis that is based on up to date evidence-based practice while offering complementary and integrative modalities of healing.

The challenges in evaluating evidence is further impeded by concerns of contamination and/or adulteration

of herbal products. Below is an example that occurred in the US that has had a great impact and propelled

efforts adopting Good Manufacturing Process (GMP) for supplement production.

PC SPECS is a patented mixture of eight herbs: reishi mushroom, baikal skullcap, rabdosia, dyer’s wood,

chrysanthemum, saw palmetto, Panax ginseng, and licorice, sold as a dietary supplement to support prostate

health. Patented in 1997, each individual herb is thought to have anti-tumor effect [64]. Initial laboratory

and animal studies suggested that PC-SPECS inhibited prostate cancer cell growth and caused decreases in

testosterone and PSA expression [65]. The supplement was recalled in 2002 after the discovery of contaminated

batches. These batches were found to contain prescription drugs that included diethylstilbestrol, warfarin

and/or indomethacin. The batches also varied in the amounts of active agents [66]. It is not known whether

the initial promising studies were the result of PC-SPECS eight active herbs or the result of adulterants.

PC-SPECS is not legally available in the United States as the manufacturer is no longer in business. There

continues to be products marketed as substitutes for PC-SPECS that have not been subject to rigorous

laboratory or clinical trials to establish safety and efficacy [67].

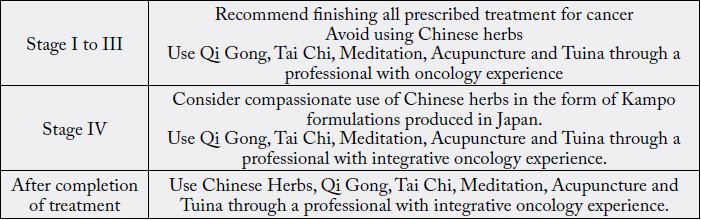

Because evidence is neither complete nor up to date, evidence-based approach should take account of its

limitations. For patients where definitive treatment and outcome is well documented, the safest course of

action may be to let the active cancer treatments be completed before considering Chinese herbs. However,

for patients with Stage IV cancer without definitive treatment, a pragmatic approach taking account of

patient preference, comfort of the oncologists and evidence-based estimation of benefit to harm ratio of

Chinese medicine, including Chinese herbs could be beneficial to patients. Because Kampo formulations

produced in Japan are classified as pharmaceutical, there is a rigorous quality control. Therefore, for cancer

patients, the authors recommend the use of Kampo formulations made in Japan specifically.

Conclusion

Authors recommend following SIO recommendations in patients who are undergoing active cancer

treatments with cancer stages I to III. For patients who have completed treatment, individualized evaluation

of using Chinese medicine that includes Chinese herbs may offer some benefit for overcoming fatigue,

neuropathy, and weight loss. For patients with stage IV cancer, with the consent of patient and patient’s

oncologist, a discussion on compassionate use of Chinese medicine that includes Chinese herbs should be

explored.

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!