Biography

Interests

Opeyemi Odejimi

Department of Psychiatric Liaison, Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health Foundation Trust, Birmingham, United Kingdom

*Correspondence to: Dr. Opeyemi Odejimi, Department of Psychiatric Liaison, Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health Foundation Trust, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

Copyright © 2019 Dr. Opeyemi Odejimi. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

In the United Kingdom, of the involvement of individuals or patients with long term disease conditions (commonly referred to as services user) together with their families or friends (also referred to as carers) commonly referred to as Service Users and Carers Involvement has become a necessity in many health and social care education programmes. There are limited studies that have evaluated its impact in students’ education. This paper discusses the expected beneficial outcomes of involving service users and carers’ in health and social care pre-registration degrees. In particular, it will focus on the expected beneficial outcomes to the three main stakeholders in higher education which are: service users and carers, students, and academic staff. This paper was developed from a conference discussion. Eight main beneficial outcomes to the three main stakeholders were identified, of which three were similar to both staff and students. This paper shares these findings and considers it as a potential benchmark for future exploration of the impacts of involvement in health and social care pre-registration degrees to the three main stakeholders.

Abbreviations

CHC - Community Health Councils

GMC - General Medical Council

HEIs - Higher Education Institutions

HPC - Health Profession Council

NMC - Nursing and Midwifery council

NHS - National Health service

PhD - Doctor of Philosophy

PRSBs - Professional Statutory and Regulatory Bodies

SUCI - Service Users and Carers’ Involvement

Introduction

In the United Kingdom, there is a widespread acceptance of the involvement of individuals or patients

with long term disease conditions (commonly referred to as services user) together with their families or

friends (also referred to as carers) in health and social care education. Although, Service Users and Carers’

Involvement (SUCI) have always existed in the education of health and social care professionals [1] however,

involvement was limited to certain educational activities such as: teaching and assessments of students’

performance [2].

The push towards more meaningful service users and carers involvement within Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) have resulted in many Professional Statutory and Regulatory Bodies (PSRBs) of health and social care courses such as Nursing and Midwifery council [NMC] [3], General Medical Council [GMC] [4], Health Profession Council [HPC] [5], Royal college of Psychiatrists [6] either necessitating or recommending active involvement of service users and carers in health and social care education.

Chambers and Hickey [5] have identified three main drivers for involvement in health and social care education and these includes: government legislations; the media; as well as the public, service users and the carers themselves. This push has resulted in nearly all educational activities such as: designing educational activities, implementing educational activities, evaluation of students’ performance, teaching, quality assurance and monitoring and many more having more service users and carers input than in time past.

The three main stakeholders who are mostly affected by service users and carers’ involvement in higher education are students, academic staff and service users/carers [7,8]. Although, there is a fourth main stakeholder group, the practice partners/mentors whose main responsibility involves students training while on placement. However, with regards to involvement within the university and classroom, these three individual groups identified above are the main stakeholders. The rationale for focusing on the expected beneficial outcomes on the three main stakeholder groups is because the impact of SUCI potentially differs for each group [9].

Typically, involvement in education is carried out with the aim that it will positively impact students. Reported benefit to students includes: developing effective communication skills, gaining insight into service users’ experiences, challenging preconceived myths and misconception, understanding diverse service users, and putting theoretical knowledge into practice [2,5,10,11].

It is also acknowledged that involvement is beneficial to service users and carers. It is said to make them feel: being valued, listened to, and respected, their self-confidence and self-esteem enhanced. It is also a possible source of income and they develop a social role [2,5,11,12-15].

Furthermore, there is a growing recognition that academic staffs are also one of the main stakeholders of involvement in health and social care education. Chambers and Hickey [5] identified academic staff as the second potential facilitators and barriers of service users and carers’ involvement. In addition, Felton and Stickley [16] referred to academic staff as gatekeepers with the power to develop or inhibit active involvement. However, there are limited studies that have identified potential outcomes to academic staff, instead more attention has been placed on power shift, scepticism and tensions that occur while involving service users and carers [16-18].

The drawbacks of involvement are mostly issues around services users and carers recruitment, selection, training, involvement, retention and sustainability, cost of delivery as well as remuneration of service users [2,10,11]. Besides, Dogra et al., [19] identified lack of expertise (in terms training and educational qualification) of service users and carers as another drawback.

In addition, some studies have highlighted that involvement could be rather upsetting to the students especially when the service user dies [20]. Also, other researchers have reported students feeling anxious, embarrassed and generally unnerving while interacting with service users and their carers [21-23]. All in all, Morgan and Jones [10] indicated that continued interaction between service users and carers with students often results in some of these emotions fading away.

There is growing research on service users and carers involvement, however majority of these researches have focused on the process of involvement with the aim of avoiding tokenistic involvement rather than evidencing the outcomes [15]. Thus, currently there are limited studies on the evaluation of involvement in health and social care education [2,5].

This article draws upon a conference discussion as well as previous research studies in identifying the outcomes of active service users and carers’ involvement in health and social students’ education. Specifically, this paper will discuss the expected beneficial outcomes anticipated as a result of carrying out service users and carers’ involvement. It is believed that this study will serve as a foundation for conducting further studies that evaluate the impacts of SUCI in health and social care students’ education.

Materials and Methods

This paper developed from a group discussion that took place at the “patient and public involvement conference:

sharing experience to inspire excellence” on the 19th September 2014 at the University of Wolverhampton, United

Kingdom. Ninety-four delegates ranging from service users, carers, students, academic staff, commissioners,

non-academic staff, local hospital staff, managing directors of local hospital and many more attended the

conference.

Nearly all the delegates who attended the conference were familiar with the concept and/or experienced service users and carers’ involvement in some ways. There were 5 main conference themes with each theme having 4 parallel sessions; each session lasted for 30 minutes with delegates given the choice of attending any parallel session. The paper was selected under the theme- “meaningful patient and public involvement in health and social care education”. At the time this study was conducted, the researcher was a PhD student at the university of Wolverhampton and abstract submitted for this conference was accepted for poster and workshop presentations.

Ethical approval to conduct the PhD study had already being obtained by the University of Wolverhampton, Faculty of Education Health, and Wellbeing ethics committee prior to the conference. The researcher and some of the participants worked within the same organisation and it was anticipated that some of the views elicited may be critical. Thus, to ensure ethical integrity participants issues of anonymity and confidentiality were addressed and informed consent were obtained before discussions began. Delegates were informed of what the workshop will entail, and it was stated that those not willing to participate were free to attend other parallel sessions.

22 delegates attended this workshop comprising of: students, local commissioners of services, academic staff, local hospital staff as well as service users and carers. This was further divided into groups of 3-5 persons to allow for in-depth discussion, in total 6 groups were formed.

The question posed to the group was:

As a result of service users and carers’ involvement in education, what changes are you looking out for in Students’ education and learning, Service users and carers as well as Academic Staff?

Each group had 15 minutes to discuss their views and have it written down in few words, phrases, or sentences, which was then later fed back to the whole group. All groups were encouraged to indicate at least one outcome for each stakeholder group.

Content analysis was carried out to identify common themes. According to Smith [24] content analysis allows themes to emerge from qualitative data by reducing the information to a manageable form without jeopardising the main content or message behind the data. Therefore, content analysis was used to generate the expected outcomes of active service users and carers’ involvement for the three main stakeholders of health and social education.

Findings and Discussion

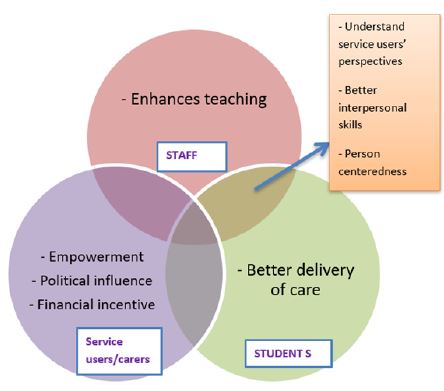

Exploration of participants’ views about the expected outcomes of involvement to the three main

stakeholders in health and social care education produced eight main themes of which three were common

to both academic staff and students. Figure 1 shows the thematic map illustrating the expected outcomes

of involvement to all three main stakeholders. These themes are now presented with verbatim quotes from

each participant group. A code G has been used to represent groups and each group given number 1-6 in

brackets following any quotations.

All groups identified that service users and carers’ involvement will allow students to understand the service

users and carers’ perspectives. It was also stated by three groups that it will provide a similar opportunity to

academic staff. These groups believe that involvement impacts academic staff and students in a similar manner.

Moreover, it is assumed that both staff and students will become aware that there might be differences

in opinions while delivering care and services, thus, they will have to come to terms that service users and

carers can exercise autonomy and their decisions should be respected.

“Students will see both sides of the situation from patients and care givers”- G2

“Just because lecturers are the professional, they are not the experts; involvement helps them to see different perspectives” G5

The traditional paternalistic manner of professionals “knows it all” and a top-down approach was a common practice of delivering health and social care [25]. However, this has now been challenged and professionals have been strongly encouraged to hear and listen to service users and carers’ opinion. Moreover, scandals such as the Mid-Staffordshire Hospital [26] have further pushed for this approach. It is presumed that the scandals could have been averted if professionals had understood the perspectives of service users and carers.

There are emerging studies indicating involvement allows professionals and students gain insight into service users and carers’ worldview making them understand their perspectives [2,5]. All in all, it helps to promote co-production in decision making. Furthermore, it is gradually being recognised that there might be conflicts between the health and social care professionals and service users/carers perspectives [27,28]. Interestingly, both are mostly aiming for the same outcome. However, acknowledging that there will be differences in perspectives, especially due to variation in preferences and expectations by health and social care professionals and service users with their carers will best equip all parties during decision making [29].

Interpersonal skills such as: listening, empathy, communication and respectfulness were pointed out as some

of the expected beneficial outcomes for involvement.

“Staff will be able emphasise” - G2

“Better communication skills for students”- G4

“Students have empathy in line with 6C’s and not sympathy”- G3

“The students will learn to respect”- G6

“Students will be better listeners”- G5

This expected outcome to academic staff and students is consistent with previous literature which expresses that involvement will result in modification and acquisition of interpersonal skills needed to deliver better care in the future [23,30,31]. Some studies have found out that there was no significant difference in skills modification and acquisition when service users and carers involvement was compared with other teaching methods such as: the use of simulated patients (actors) or audio/video tape recording [32].

However, it is believed that the context these two studies took place could have affected the result of the study yielding no interpersonal skills modification and acquisition. Eagle et al., [32] indicates that that involvement may contribute little to the technical skills required of professionals such as setting intravenous line, operating equipment and many more, nevertheless, involvement serves as a good reminder and equally reinforces the importance of interpersonal skills to students’ practices.

Nearly all group expressed that academic staff and students will become person-centred because of service

users and carers involvement.

“Students learn to see person first and not only condition when caring”- G6

“The students see service users as partners and not just do care”- G5

“Staff will see people as individuals”- G5

Comments from the participants indicated that on many occasions’ health and social care services are delivered as expected, however, something is usually missing. There is no doubt that other factor such as physical, mental and social well-being of an individual greatly impact on the health and wellbeing of individuals [33,34]. Thus, it is believed that involvement will place individuals at the focal point, rather than professionals only focusing on service users and carers health and social care circumstances. Overall, it will make professionals more aware of other factors that impacts health and wellbeing and ensure service users are treated holistically.

All groups stated that service users and carers’ involvement will allow students to become better health and

social care professionals. It is assumed that involvement will make students more knowledgeable, competent,

and critically reflective of their practices.

“Students have better knowledge”- G1

“They (students) may become more proficient when delivering service”- G3

“They (students) are reflective” - G6

It is believed that involvement in health and social care education will allow students develop useful skills and attitudes that will help deliver better health and social care [4]. This view is consistent with previous studies expressing that students gain better understanding of patient’s health conditions, become more selfaware; and reflective of their practice as a result of involvement [21,35-37].

Furthermore, this opinion is supported by many regulatory and educational bodies of health and social care education. They have indicated that involvement will produce better health and social care professionals in the future. This is one of the major reasons that are recommending or necessitating involvement in their degree. This is not to say that studies have not reported some drawbacks of involvement to students. All in all, it is believed that the benefits of involvement outweigh those drawbacks.

It is believed that involvement is beneficial to the staff because it enhances their teaching in a unique

manner. Participants’ comments to illustrate this view are illustrated below:

“Changes in content of module”- G1

“Developing meaningful learning outcomes in health and social care education”- G4

“Tailor lectures and courses to include patients and service users”- G3

“Linking theory to practice for students”- G1

These views are consistent with existing literatures on involvement which have reported that it improves the learning outcomes of health and social care courses and this subsequently provides a better learning experience for students [12,38,39]. Studies have reported that service users and carers taking part in: sharing their experience, role-playing health and social care scenarios or conditions, teaching, course design and delivery, developing learning materials and new modules, and providing feedback have immensely complemented academic staff teaching role [21,22,25,31,39-41].

Moreover, involvement ability to bridge the gap between theory and practice is also considered one of its distinguishing factors [5,10]. Traditionally, classroom-based teaching of health and social care courses have been designed to impact knowledge and technical skills within the classroom which are then subsequently put into use while in practice (placement). Thus, involvement integrates the practical aspect of the training into classroom teaching and keeps students learning focused on what is deemed important to service users and carers.

There is no doubt that involving service users and carers can sometimes be challenging to academic staff, especially due to their busy workload schedule. Preparation and debriefing of service users and carers before/ after a session have frequently being reported as the most challenging task for academic staff carrying out involvement [36,38]. However, the experience service users and carers’ involvement bring into the classroom and university as a whole is very valuable and has been reported on several occasions to make the learning experience more real and meaningful.

All groups indicated that involvement empowers service users and carers, providing them with a voice that

is heard and listened to. This is because it allows service users and carers to be viewed not just as recipient of

care but equal partners.

“Service users and carers being heard”- G2

“Opportunity to be listened to”- G1

“They (service users and carers) Feel included and not vulnerable”- G3

“Boost their (service users and carers) confidence”- G3

This view is consistent with existing literatures which indicates that one of the greatest benefits of involvement to service users and carers is the feeling of being valued and heard [2,5,10,11,13,14]. Involvement not only provides the opportunity to be heard by professionals but also gives them a voice that is heard and listened to by statutory and regulatory bodies. This may ultimately shape the thinking and behaviour of future health and social care professionals. This view is supported by the Francis report [26] recommendation and constituted why there was a push for involvement.

It was expressed by two groups that involvement has the tendency to influence politics and political leaders

particularly about what’s best for service users and carers.

“To avoid cutbacks”- G6

“Government have more knowledge before cutbacks”- G6

“Better security for service users”- G2

There is no doubt that politics is intertwined with the movement of service users and carers involvement [42,43]. A look into the history of involvement in England indicate that the first formal structure put into place by the Community Health Councils (CHCs) in 1974 was established with the purpose that it will represent the views of service users and the public about the health and social care services delivered by the National Health Service, popularly called NHS [44,45].

According to Hogg [46], in the 1970s it was noted that local communities were not benefiting from national policies and resources were unevenly distributed especially for marginalised individuals (such as: the disabled, individuals with mental illness and the elderly); therefore, it was proposed that service users involvement would help adjust this unevenness, and the CHCs were formed to be an advocate for deprived communities as well as bridge the gap between the NHS and local authorities. Over the years, involvement has provided a platform that allows service users and carers to campaign for better services [36]. Nevertheless, social and political climate usually determines the extent to which the views of service users and carers are taking into consideration during decision making [47].

At the time this workshop was conducted, there was global economic crisis in the UK. This resulted in the government using austerity measures which led to budget constraint within the National Health Services (NHS) resulting in cutbacks of some health and social care services, despite the free universal health coverage system to the citizenry. Participants did make clear that they are aware cutbacks by the government are inevitable due to the present economic situation of the country. However, service users and carers should be consulted and involved in decision making process before the verdicts are made.

Only one group indicated that service users could potentially benefit financially from involvement.

“Financial parity for service users”- G3

In the group this comment was made, one of the participants was from the local commissioning service and works closely with the pension services. The group were glad to mention that the service users and carers should be paid volunteers because most service users and carers are unemployed or pensioners or dependent on the government for their warfare. The group felt that service and carer being paid volunteers was a gesture that signifies their time and effort is deemed a valuable contribution to education.

Although, there is an ongoing debate about payments of service users and carers for their involvement and the likelihood of this viewed as a tokenistic gestures [48]. This is because many organisations that involve service users and carers will not like to be viewed as being unethical, exploitative, or perceived as being unfair if payment of service users and carers is considered irrelevant [2,42,49].

Some have questioned if payment of service users and carers is one of the motivation for their involvement, however, research has shown that altruism remains one of the greatest drive for involvement, especially in student’s education and training [10,48]. Hence, financial incentive could contribute immensely to service users and carers being valued [48,50].

Conclusions

This paper has highlighted a number of desirable outcomes to all three main stakeholders of active service

users and carers’ involvement. This limitation of this paper is that it focuses more on the desirable outcomes

of involvement for the three main stakeholders. However, the duration of the group discussion did not

facilitate more time to discuss some of the drawbacks and how to overcome such drawbacks. Also, it should

be noted that the viewpoints shared in this paper could be situational specific and perceived outcomes of

involvement might have changed over the years.

Nevertheless, this paper provides an assurance that active involvement can bring about a shift in health and social care education in a more positive direction. Also, a balanced view of the outcome to all three main stakeholders has been discussed within this paper. All in all, this paper may provide more awareness of the possible advantages of involvement to all three main stakeholders and serve as a basis for further exploration of its impact in Higher education. Besides, it may inform researchers and education providers in countries or health and social care degrees were involvement has not been recognised as the norm. Thus, future research is required to evaluate the impact of service users and carers’ involvement to the three stakeholders in higher education. In addition, longitudinal studies are needed to identify if the skills and knowledge acquired by students are sustained in practice over a long period of time.

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!