Biography

Interests

Tayyib, N., Alsolami, F., Asfour, H. I., Alshhmemri, M. S., Ramaiah, P., Ahmed, E., Alsulami, S. A., Ali, H. Y. S. & Lindsay, G. M.*

College of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi Arabia

*Correspondence to: Dr. Lindsay, G. M., College of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Umm Al- Qura University, Saudi Arabia.

Copyright © 2021 Dr. Lindsay, G. M., et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

Blended e-learning is being increasingly used across major sectors of the educational environment

including medicine, nursing and healthcare. This trend can be seen through the increase in scholarly

articles and research on the subject.

A literature review was conducted using the search terms ‘In Title: blended learning’ and ‘In Title:

blended learning nursing’ in the Google Scholar and PubMed databases from the year 2000 to the

year 2020 inclusive.

The definition of blended learning is broad and therefore its interpretation has the potential for the

learning process to be displaced from its theoretical basis. This is a particular concern for disciplines

of a strongly serial nature. Thus transparency in the blended learning concepts is important to ensure

that benefits to student learning via blended learning are clear. Five constructs are identified and

are widely reported as measures of successful learning within an e-blended learning environment.

These constructs should be recognised when revising or developing a blended learning curriculum

to eliminate any detriment to the learning contexts.

Educational curricula have many components that are clearly articulated in specific activities,

content, intended learning outcomes, educational levels and timelines within course descriptors.

Without strategic planning the ill-defined concept of blended e-learning being implemented

in an unchecked manner could lead to disruption in existing systems. A systematic approach to

implementation mirrored by an integral evaluation framework is recommended to facilitate this

process and provide feedback on its value and utility.

Introduction

The year 2020 has seen countries worldwide responding to the threat posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The World Health Organisation [1] advised, and governments across the world responded by implementing

population ‘lockdowns’ which requirements of social distancing have led in many cases to components of

face-to-face teaching being replaced with online teaching in educational institutions ranging from schools

to universities. This expansion of curricula into a combination of face-to-face and online education is called

‘blended e-learning’ and is becoming a popular approach to providing educational curricula, not just as a

consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Literature Search

A literature review was conducted using search terms ‘In Title: blended learning’ and ‘In Title: blended

learning nursing’ in the Google Scholar and PubMed databases from the year 2000 to the year 2020 inclusive

(according to PRISMA flow diagram; © Copyright 2015 PRISMA) [2].

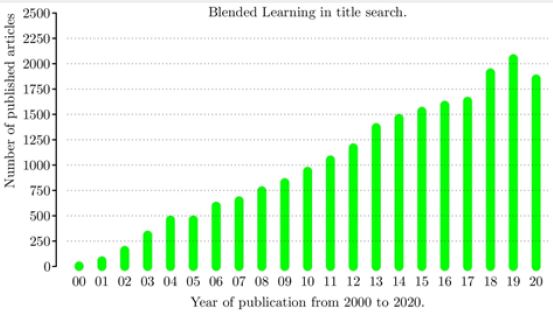

The initial task was to understand the extent to which scholarly articles were focussed on the subject of blended learning. Figure 1 shows a Goggle Scholar count of the number of published articles over the period from 2000 to 2020 inclusive in all subject areas with the term ‘blended learning’ in their title. Clearly the number of articles has shown a several hundred-fold increase over this period.

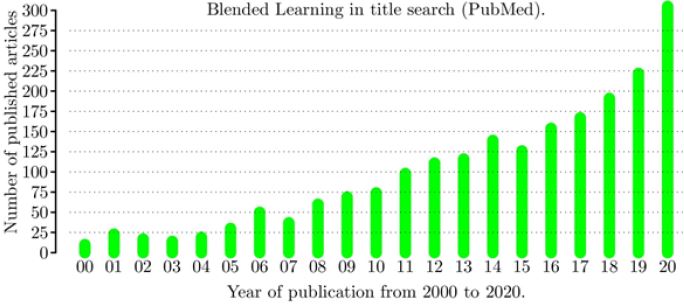

Figure 2 shows the result of a search in PubMed counting the numbers of articles with the term ‘blended learning’ in their title from the year 2000 to the year 2020 inclusive. The results show an approximately 10- fold increase in published articles over that period.

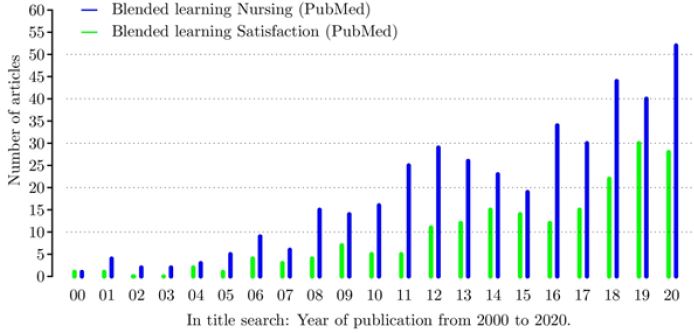

Figure 3 presents the results of a second search of PubMed over the same period but with a title search containing the term ‘blended learning’ and at least one of the terms ‘nursing’ (blue bar) or ‘satisfaction’ (green bar). Figure 3 indicates how blended learning in Nursing has largely developed over the period 2008 onwards.

Arguably the growth in the application of blended learning across the board has been largely driven by the expansion of user-friendly interactive technologies and network capabilities from 2000 onwards, and particularly with the introduction of the first 4th Generation (4G) system in December 2009 and more recently with the introduction of the first 5th Generation (5G) system in April 2019.

Numerous definitions of ‘blended learning’ exist with debate continuing about its theoretical basis because of the various mixed learning assumptions and methods that are used [3]. The general definition describes instructional approaches which combine elements of e-learning with the traditional classroom environment [4-6].

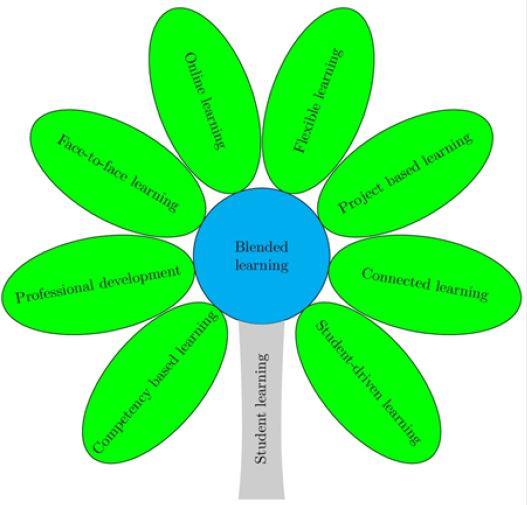

Figure 4 illustrates how blended e-learning can offer simultaneously the benefits of e-learning, face-toface classroom environments together with a range of teaching and learning approaches appropriate to the educational programme, students and educators.

A range of approaches are available and it is important that there is transparency in the identification of the blended learning concepts being selected to ensure that student learning via blended e-learning retains it theoretical ‘building blocks’. In addition, the balance of the constituents of a blended e-learning curriculum in practice, and how this balance might be discipline dependent should be considered.

Therefore, with so many alternative approaches available, it is incumbent on planners of educational curricula to ensure that the selection of components of the educational blended programme is guided by established educational curriculum development processes.

Blended E-Learning and Student Experience

Five constructs have been used and are widely reported as measures of successful learning within an e-blended

learning environment [6]. In this review these constructs will be considered in the context of blended learning approaches to provide multiple perspectives on the learning experience in a blended e-learning

environment. The following literature has been reviewed to summarise the evidence that supports successful

blended e-learning.

A significant amount of “real learning” occurs during inter-personal interactions with teachers and can

assist in learning assimilation, analysis, synthesis, applying knowledge, problem solving and be socially and

educationally beneficial with blended learning modes yielding positive results [7-9]. Battalio [10] using a

criterion approach likewise argued that good learner-instructor interaction is a pre-requisite for effective

learning. Indeed, many studies have found that both the quantity and quality of learner interactions with their

peers and instructors are highly correlated with learner satisfaction in almost all learning environments. Active

engagement of learners should be facilitated in the blended learning environment, and as recommended by

Jaggars et al. [11], educators should explore creative ways to increase their online presence. Strong educator

or instructor presence in combination with quality course content have been recognised from the early days

of e-learning to be essential elements in courses that facilitate successful online student engagement with

their learning and influence learner evaluation of that learning [12,13].

Establishing educator presence in online courses can be achieved in a number of ways, such as through regular communication with students by conference calls or chat rooms, consistent feedback and critical discourse initiated by the instructor. Online learners should feel connected to the instructor, to other learners in the course and to the course content [14,15]. This state can be achieved in a supportive learning environment in which educators strategically combine audio, video, synchronous and asynchronous discussions, practical activities and other online tools to engage learners. One way to sustain motivation is not to lose the personal connection that already exists between instructors and students [16]. An online survey conducted by Bolliger & Martindale [17] found instructor perspectives, technical issues and interactivity to be the three central components of education practice determining student satisfaction, and concluded that satisfaction with course design, course contents, the facility to access and visualise information on the teaching platform and the possibility of interaction are critical factors underlying student motivation which is so essential for student success.

Other researchers also report this recommendation. For example, in a comparison of student satisfaction with traditional and blended e-learning components of a course, Napier [18] found that satisfaction was associated with the quantity of interactions with instructors for both educational approaches. Other researchers also point to the importance of the instructor as a motivating figure upon whom successful completion of a course largely relies [15]. This trend extends also to the learning environment of web based on-line e-learning where again, the presence of interactions between instructors and students was associated with greater satisfaction.

Melton et al. [19] studied the effectiveness of blended learning in an undergraduate health course using student satisfaction and achievement outcomes. Using a quasi-experimental research design, classroom only teaching was compared with a blended learning approach via measurements of course grades, learner satisfaction and instructor evaluation. They found that students in blended courses were significantly more satisfied, although there was no significant difference in grades between both groups. López-Pérez et al. [20] likewise reported increased learner satisfaction with blended learning in a review study involving 1,431 students, and also reported that courses using blended learning achieved higher retention rates and higher examination marks.

Although learners have reported greater satisfaction with blended e-learning courses when compared to traditional face-to-face or fully online class delivery [21-23], the underlying reasons for this finding are not easy to unravel. The effectiveness of blended e-learning is influenced by many factors within the mix of the online and classroom components, their constituent activities, and in particular the degree of student interaction/engagement with the instructor, and whether or not this is synchronised within the learning contexts [6,24]. These views are echoed by Nortvig et al. [25] in a large systematic literature review comparing outputs from the e-learning and blended learning literature in relation to student satisfaction (n=44). These authors concluded that teaching and learning achievements are influenced by more than format alone, and they specifically identified positive feedback/satisfaction with ‘educator presence in an online setting’, ‘the facilitation of student-student interactions’, ‘student identity and support’, ‘interest in students learning progress’, ‘respect for students’, ‘accurate specific feedback’ and the need for ‘clear connections’ across ‘onlineoffline activities’, and where relevant, ‘theory-practice’ areas of learning. Supplementary to these desirable educational factors, other authors have postulated the need for students to feel a sense of belonging to a learning community, engaging academic content and a strong teaching presence endorsing the long standing principles articulated within teaching and learning meta-paradigms [26,27]. In a large student survey undertaken by Banerjee, [28], students reported high levels of satisfaction but added that blended learning classes also required more effort and involved wider reading and preparation. Specifically, students commented that the online presence of their instructors had a positive impact on their engagement and learning.

A recent meta-analysis by Ebner & Gegenfurtner [29] explored the effectiveness of face-to-face teaching compared with synchronous and asynchronous online learning. These authors concluded from a practical perspective and from the perspective of satisfaction that face-to-face teaching was marginally more effective than synchronous e-learning, but that both were better than asynchronous learning. They further highlighted that in times of radical transition to online learning, course design can often be simplistic and considered inferior to face-to-face instruction resulting in a lack of engagement and a possible compromise to learning. Palloff & Pratt [30] make the important point that a successful transition from classroom to online teaching is not just a matter of transferring teaching materials from one format to another, but is one in which the role of the educator is to facilitate rather than lead. It has been suggested that e-learning should focus on higherorder skills such as creative thinking and problem solving in order to engage students more effectively in the e-learning context [31]. Courses which provide opportunities for learners to interact with each other will be automatically enhanced independently of instructor involvement.

Learners reported greater satisfaction with their learning experiences when they felt themselves part of a

family of learners receiving detailed feedback, engaging in face-to-face interactions with faculty [32,33]. Interaction was regarded as the concept of presence, a state in which students feel that they are part of a

group or “present” in a community motivating them to wish to participate actively in the activities of the

group and share important community learning value, instructor enthusiasm and rapport. Arbaugh [34]

suggested that e-learning satisfaction is significantly positively correlated with learner interactions with

others, while Alvis & Rapaso [35] highlighted that adherence to online discipline is another key factor

underlying effective blended e-learning.

Classroom interactions include a significant amount of “real learning” where learners can assimilate information, use software, apply knowledge to problem solving, and interact with the instructor and other learners [36]. Previous research has already identified learner isolation and lack of communication as potential drawbacks with e-learning [37] and so this is clearly an enduring issue and perhaps the balance of time spent within the wider curriculum can be adjusted to take learner isolation into account. Despite the fact that most results show satisfaction among users, Dzakiria et al. [38] recommend a need to have learning support in order to facilitate blended learning. Efforts to enhance the connectivity of learners within the e-learning environment should be considered in programme designs, particularly when remote working is in place. In a US study of almost 400 students, critical success factors with e-learning success indicated that instructor‐learner dialogue, learner‐learner dialogue, instructor, and course design significantly affect learners’ satisfaction and learning outcomes. The findings went further to state importantly that both extrinsic learner motivation and learner self‐regulation had no significant relationship with user satisfaction and learning outcomes [39]. This would indicate that the satisfaction and learning achievements are determined by intrinsic interactions and qualities within the e-learning environment as opposed to the disposition of the learner.

The synchronous delivery of e-learning has been shown to correlate with higher overall satisfaction than

asynchronous e-learning [40]. Computer self-efficacy was reported to be related to satisfaction in online

learning [41], but as user interfaces become more user-friendly and share more commonality, the skills gap

in computer operation across users is being systematically reduced. Some argue that contemporary learners

are already competent with today’s e-technology interfaces through their use of the widespread personal

digital technologies [42]. Other investigators found that student learners feel that they could be better

skilled in technologies with additional focussed IT training in systems and personal technologies such as the

in-class use of laptops or tablets [43].

Skilful design of technological applications, for example the introduction of links and feedback loops, has been shown to foster student engagement through their ease of access, interactivity and learner control [44], and consequently enhance student performance and course satisfaction [45,46]. Individual computer selfefficacy, system functionality and technical support for learner-learner and learner-instructor interactions contribute one of the primary determinants of satisfaction with e-learning. Keengwe et al. [47] found that learners’ expectation of the effectiveness of technological tools in online courses was critical to understanding the concept of satisfaction in online education. These authors further reported that satisfaction was most impacted by learning convenience combined with the effectiveness of e-learning tools. The education literature contains suggestions that benefit can be gained from ‘unbundling’ academic programs and curricula and implementing strategies to embrace diverse change in technology culture, such as bring your own device (BYOD) [48,49] to promote contemporary learning mechanisms.

By contrast, direct solely online modes of e-learning have been reported to present barriers in course participation and the learning process itself due to the absence of technical support and minimal interaction between learner and instructor [6,50,51]. The delivery of e-learning which is adaptable, with ‘in time’ instructor’s response, perceived ease of use and course applicability have been noted to contribute to satisfaction [52]. The high rating of interactive learning mediated by technology was evident within a large online learning education system (Open University, UK http://www.open.ac.uk) involving the delivery of over 150 modules to 111,256 students via centralised online and distance learning formats. Rienties & Toetenel [53] examined the linkage between student interactions in approximately 400 million minutes of student online behaviour, student satisfaction and student performance. The principal findings were that the largest predictor for academic retention was the time learners spent on interactive communication activities. But these activities were theoretically-designed communication tasks that aligned with learning objectives [53]. These findings strongly endorsed the importance of interactive learning processes, a robust educational basis and techniques for designing interactive online material. The specific types of digital technology chosen to deliver a course is considered to be less important than the types of learning activities undertaken, the time spent on task, the degree to which the learning pedagogies facilitate learner-teacher and learnerlearner interactions, and whether or not the pedagogy encouraged reflection about what was being learned [54]. In addition, within a blended e- learning curriculum, the balance between e-learning and traditional lecture-based teaching is likely to influence the impact of technology on learning and is therefore a factor for consideration within the overall course design [9].

Dang et al. [55] report that computer self-efficacy could significantly affect perceived female satisfaction,

enjoyment and their assessment of their accomplishment in the blended learning process, whereas no such

effect was observed for male students. Computer culture and internet engagement have also been associated

with gender differences in respect of how each gender uses technology and their underlying proficiency [56].

Traditionally males have been assumed to have better proficiency and more online experience than women

[57]. Nevertheless, neither gender roles nor technology can be treated as stable entities [58]. Indeed, there

is evidence supporting the view that men and women express varying degrees of anxiety, acceptance and

interest in new technologies across time, and that the gender gap is narrowing over time [59,60]. Women

have been reported to treat computers as devices for active communication using social media and to prefer

working in groups whereas men are more likely to solve problems on their own [61]. Such reported genderrelated

differences in the use of technology may influence the application of IT skills within an educational

context and should be recognised when designing activities to suit a range of capabilities.

The ubiquitous use of digital technologies in everyday life during the last decades has concerned some

authors that it might be widely assumed that all are equally prepared in their ‘know how’. This assumption has resulted in the ‘millennial generation’ being regarded as ‘digital natives’ with an emerging skill set

encompassing technological skills allowing them to manage any technology they meet. Others, however,

point out that digital technology skills learned from personal use may not transfer to the technical skills

required in the educational setting such as command vs. menu-driven or sound vs. visual operating modes

[42,62]. Furthermore, a large US survey of undergraduate students reported that students could be more

effective learners if they had better technological skills including learning management systems and personal

technologies such as the in-class use of laptops or tablets [43]. Therefore, technological skills training should

be introduced as a foundation course as curricula become increasingly reliant on digital technologies.

Discussion

Blended learning offers many educational advantages, one of which is the flexibility of not always needing

to be on-site thereby saving time and travelling costs and providing for many the opportunity for more selfdirected

study that could be better integrated with personal and family life [63]. These authors found that

average learner satisfaction with blended e-learning was higher than that based on traditional methods alone,

although this finding masked the fact that while high achievers (as measured by grades) preferred blended

learning, poorer achievers tended to favour face-to-face teaching, and that this diversity of experience was

also reflected in learners’ willingness to engage in future blended learning. They speculated that this behaviour

may be explained by how different achievers value/use the time released by a blended learning programme,

time that would otherwise be unavailable in a formal teaching setting.

An important element supporting the growth of blended e-learning is how young learners are becoming increasingly adept at managing computer technology and negotiating various systems for the electronic exchange of information. These ancillary skills are essential for the effective delivery of a blended e-learning programme. Albanna & Abu-Safe [64] report that the indirect integration of information technology into the learning environment enriches the teaching and learning experience, and for many creates a better quality of education, while Hewson [65] notes the reduced cost and time saved by the automated delivery of information and management. While many argue that contemporary students are already competent with today’s e-technology interfaces through their use of the widespread personal digital technologies [42], other investigators found that student learners feel that they could be better skilled in technologies with additional focussed IT training in systems and personal technologies such as the in-class use of laptops or tablets [43].

Blended e-learning, however, is not without its disadvantages. Most obvious are the technological challenges presented by the need to provide efficient networking systems, effective training facilities and suitable hardware and software. For example, a pre-requisite for the wide spread use of blended e-learning is quality and affordable internet access fot the public at large. Another well-recognised difficulty is that directly porting teaching materials used in face-to-face instruction to online teaching is not effective. Consequently, there are significant up-front investment costs in developing online teaching materials before the benefits can flow. Easy access to the web also raises the issue of guaranteeing fair and meaningful assessment and counteracting the spread of disingenuous information. Figure 5 gives a schematic representation of traditional curriculum learning. Specifically, components of a traditional curriculum, although variable, are nevertheless relatively well defined and follow well-defined directions and inter-relationships with each other.

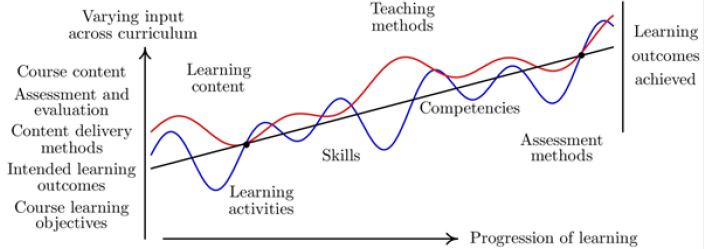

By contrast, the possibility of a blended e-learning curriculum with additional components of instruction could be more difficult to adhere to the theory and concepts that educational curriculum as based, illustrated schematically in Figure 6. This impact of this behaviour will be particularly pronounced effect when a blended e-learning approach is used widely in a curriculum creating a climate in which there is the potential for the educational experience to become sufficiently complex that strands of learning potentially interact such other essential components of learning fail to be covered or are not synchronised. This would be particularly challenging in disciplines in which learning builds in a specific order of delivery and matching of components of theory and practice for example,

Therefore adding another teaching method to an existing curriculum or in the developing of new curricula should reference known evidence-base practices for curriculum design to ensure synchronisation of all components in the learning process and to avoid creating under- and over-representations of parts of the curriculum. Assessment methods should also be attuned as teaching methods evolve [66-73].

Conclusions

Blended e-learning offers a combination of traditional face-to-face learning and e- learning in which the

proportions of each component can vary. They are typically combined in a way so as to achieve the ambitions

of the learning programme. The effectiveness of blended learning as measured by student satisfaction is

largely governed by the quality of the instruction, the quality of the interactions between the instructor

and student and between students themselves and the ability of the technology to facilitate the delivery of

educational content.

Without strategic planning the ill-defined concept of blended learning being implemented in an unchecked manner could result in incongruence with the original educational theoretical basis from which sound curricula are based. It is important to recognise that further complexity in learning methods needs to be aligned with educational goals and assessment procedures. These considerations are integral within the management of quality and standards processes.

Blended e-learning continues to be used across major education sectors including medicine, nursing and healthcare. As with any development a systematic approach to implementation mirrored by an integral evaluation framework will facilitate this process and provide feedback on its value and utility.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful for the support and guidance from the Division of Post Graduate Studies and

Scientific Research of Umm Al-QuraUniversity

Bibliography

Hi!

We're here to answer your questions!

Send us a message via Whatsapp, and we'll reply the moment we're available!